After coding data for a publication on demographic representations in vegan media, I was utterly shocked to discover that nearly all analyzed subjects were undeniably skinny. Over a twelve year span, the two magazines included in my study featured only a handful of subjects (mostly men) who were noticeably athletic, toned, or carrying “excess” body fat. Only one female subject appeared to deviate from the thin norm, but she was also wearing baggy clothing, so it was unclear.

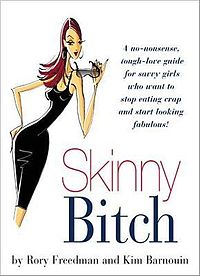

Vegan campaigns sometimes go beyond this otherwise indirect connection between veganism and weight loss and blatantly suggest that if you want to be “hot” and “fit,” you need to go vegan. Freedman and Barnouin’s Skinny Bitch is a prime example, as is PETA’s “Save the Whales” billboard campaign. The overwhelming representation of thinness in our movement is a problem in itself, but our fixation on veganism as a weight loss miracle carries with it several implications that target vulnerable populations: women, people of color, and “obese” persons.

Body shaming is especially problematic for a movement whose largest demographic is women. When we promote veganism as a means to lose weight, we normalize thinness as the ideal body type. This alienates those vegan women who do not fit within this ideal and it denigrates non-vegan women who do not fit it either. Research has shown that veganism is indeed an important variable in reducing excess body fat, but one 2005 medical report found that as much as 29% of vegans are overweight or obese. That means about 1/3 of our vegan community does not reflect the idealized thin body that represents us on magazines, websites, videos, and other lifestyle or outreach literature.

Idealizing thinness is really the idealization of higher socioeconomic class. It oftentimes takes considerable income to have access to fresh vegetables and fruits. Vegans without that luxury must rely on cheap, carbohydrate-heavy grains like flour, pasta, and potatoes. Fresh fruits, vegetables, and even spring water tend to be far more expensive than their processed counterparts.

We cannot forget that socioeconomic status is not simply about economic resources, but social resources as well. In the United States, African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics are disproportionately poor, a result of centuries of oppression and continuing inequality. They are also disproportionately located in areas with limited availability for healthful foods (rural areas and segregated inner city neighborhoods); these are known as food deserts. In The Inspired Vegan, Bryant Terry, who advocates for improving food access for disadvantaged peoples, notes that in 2007, Oakland California housed 53 liquor stores, but not a single full-service supermarket. Those living in food deserts might not have a car, could lack access to public transportation, and they may lack the time to travel out of town for healthier groceries due to work and childcare responsibilities.

Finally, the demonization of “fat” in the United States has very real and disastrous consequences for those humans unfortunate enough to fit within that socially constructed category. “Overweight” humans (especially women) can face hiring discrimination, are less likely to be promoted or selected for prestigious projects, and they ultimately make less money overall. And of course, weight discrimination can result in hurtful interpersonal mistreatment as well, like name-calling and objectification.

I can understand that many vegans enthusiastically promote veganism as a weight-loss diet, but we must be mindful that body weight is a complex social issue and the celebration of thinness can be hurtful to others who lack the social and economic privilege that most vegans enjoy. This movement is about nonviolence, and this principle must extend beyond Nonhuman Animals to include our fellow activists as well.

Vegan media sources, too, should be aware of their influential role. Consistently portraying a particular body type that is relatively unachievable for a good number of us creates a harmful and unrealistic ideal. The impact of thinness in women’s magazines is well documented. When the media is inundated with thin (often airbrushed) figures, this can seriously impact consumer self-esteem and lead to eating disorders. But some magazines like Seventeen have responded with a commitment to picturing “real” people. This should be a goal for vegan media as well.

As social activists, we should not only be concerned with the well-being of our community members, but we should also recognize that our media portrayals are influential in attracting (or repelling) certain demographics. If we consistently show thin people (or women, or whites, or higher socioeconomic status individuals), we are framing our movement as one meant for certain types of people, but not for others. Yet, I suspect that diversity will be an essential variable in achieving social change. I suggest, then, that we begin to think critically about how our movement is being represented and set our bar a little higher to include all body types and all backgrounds.

This post was originally published by One Green Planet on January 30, 2013.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.