Author: C. Michele Martindill

Within the animal rights movement there is some understanding that vegans have a responsibility to lead by example in stopping the oppression and exploitation of animals. A meme recently making the rounds of various Facebook pages is a call to positive action and leadership for all vegans:

“As vegans, we must lead the way in ending animal use, and so we must be committed to ending it. This means that we must reject exploitation and commodification of nonhumans in all its forms. We ought never seek to regulate or perpetuate that which we want to end. Don’t participate in nonveganism by endorsing it. Unequivocally embrace veganism and educate others to it.”

The message is clear. In order to end the use of animals vegans have to completely stop all use of animals and not settle for merely regulating the use of animals. Laws that try to make slaughterhouses more humane or stores that sell so-called happy meat still treat animals as products and insure their continued suffering, although the humans who consume these animals are lead to believe life is better for all concerned. The part of the message in the aforementioned meme that makes no sense in terms of veganism is the last sentence, the admonition to not equivocate in accepting veganism and to get others to learn about veganism. Why then does the organization responsible for this meme have a name and logo that reflect ageism and sexism? How can the animal rights movement consider itself inclusive of all members of society as long as any group openly stereotypes, objectifies and commodifies older people, specifically older women? If veganism is defined by a “rejection of exploitation of nonhumans in all its forms” then it’s time for vegans to realize the same call to social justice must be extended to all marginalized groups. Vegans do not get to exploit one group as a means to end the exploitation of another group.

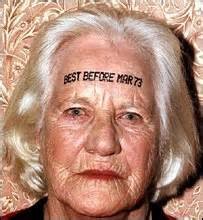

It is unfortunate when any group within the animal rights movement fails to think reflexively or critically about its role in the oppression of others. Most of the time these groups do good work on behalf of all animals and do express a desire to be inclusive in their membership, especially in terms of accepting people of all races, genders, ages, physical abilities and social classes. Still, the group Grumpy Old Vegans remains defensive over its name and logo. The group used to be named Grumpy Old Vegan (GOV) and was the brainchild of a man who quickly drew well over a thousand Facebook followers to his animal rights group, a group that focuses on abolitionist veganism. Dating back to the launch of the group, the membership has been mainly comprised of women. When GOV was approached about the exclusion of women in the leadership of the group, the name of the group became Grumpy Old Vegans, with the addition of an ‘s’ to the name which implied the leadership was not just that of one man. To further deflect criticism of sexism within GOV the logo of the group went from being a caricature of just an older man to a caricature of both an older man and an older woman. The caricatures add to the ageism by depicting the man and woman as having oversized ears and noses, toothless and pinched oversized frowns, deep and exaggerated wrinkles, baldness for the man and gray hair in an outdated style for the woman. The overall message conveyed by the name of the group and logo is that old people are always grumpy, wrinkled, toothless, and possess oversized facial features. In short, they should be dismissed as nothing more than a joke. It’s too bad the GOV group members do not see how deeply their ageism cuts.

It should be noted that the GOV group has dismissed these concerns about ageism with a litany of clichés, claiming that anyone finding ageism in their name or logo “clearly has too much time on their hands,” and that they, too, are aged fifty or older and don’t see a problem with the caricatures. One person even mentioned how the logo makes the group seem fun, a place for jokes. Others added that all that really matters are “the animals.” Not one single person tried to understand ageism or see how even if they felt fine with the name and logo, others might not feel the same way. Empathic understanding or sensitivity to the perspectives of others was nowhere to be found. Certainly if the name of the group had been Grumpy Old Women, Grumpy Old Indians or Grumpy Old Blacks, and had the logo featured caricatures of women, Native Americans or Persons of Color that stereotyped their appearance, this essay would not be necessary because most vegans know it is inappropriate to stereotype marginalized groups; nor would we need to define sexism and racism in relation to those caricatures or the resulting effects on the animal rights movement—those definitions are known and discussed throughout the movement. Now it’s time to recognize ageism, what constitutes an ageist stereotype and the consequences of exploiting older people with oppressive imagery.

Stereotyping iconography is known to incite racist attitudes as well. The popularity of redface sports imagery has necessitated heavy campaigning by Native American activists and their allies.

Ageism refers to the discrimination and stereotyping of people based on the number of years they have spent on earth, their appearance, and the perception they have diminished physical and mental capacities. Ageism is a form of oppression and exploitation, and it mainly involves ignoring older people or silencing their voices in order for younger people to assert their positions of power and privilege. On occasion the very young can experience ageism when their lives and opinions are devalued solely based on their age; however, this essay addresses ageism directed toward people over the age of fifty, those who, as economist Joanna N. Lahey (Lahey, 2006) (Barnett, 2005) observes are finding their age is making them unwanted in the work world. Employers are buying into the stereotype of older people as ill-tempered, out of touch and in physical decline. When ageism intersects with sexism the invisibility, lack of respect for and devaluing of women becomes more profound, and yet it is ignored or treated like a joke among those who have yet to see their hair turn white or those making an ill-advised attempt at self-deprecating humor. The ageism-sexism intersection is particularly embedded in (Lahey, 2006) the structure of the animal rights movement, preventing the movement from both gaining the knowledge and experience of older women, and from being regarded as an inclusive, progressive social movement.

The contributions of older women in animal liberation spaces are invaluable, and yet devalued. A group of senior women in China feed and care for hundreds of homeless dogs.

The sexism of the animal rights movement is well documented (Abolitionist, 2015). Ageism, like the older women in the movement, is largely not considered an issue. It is easy enough to point to the leading members of the movement who are older and have achieved the revered status of founders, philosophers or experts, members like Tom Regan and Peter Singer. Women are not prominent on these lists. As Rosalind Chait Barnett establishes, there are attitudes and social structures in our workplaces that leave women more vulnerable than men to the hardships of aging (Barnett, 2005). Those hardships are found in the animal rights movement, as well. While aging is seen as a state of decline for both men and women, successful men are viewed as “having grown in skill and wisdom,” [p. 26] but older women are too often stereotyped as round-tummied grandmas, kind and nurturing till the end of their days. Older women are making a strong drive to dispel this stereotype by pushing against the gl ass ceilings of their workplaces, by working in fields traditionally dominated by men, by demanding equal pay for equal work; however, none of the advancements made by women have given them secure futures in their old age. They often have to leave work to be caregivers to family members, and lose both opportunities for advancement and robust pensions. When it comes to women animal rights activists, they continue to encounter men in most of the leadership roles, to inherit strategies for activism that were created by men and to operate in social movement structures that men continue to enforce. As women animal rights activists age, if they are visible at all they are many times type-cast as nurturing and lacking the youthful exuberance of the majority of movement members (Barnett, 2005). Their online involvement in activism is too often unquestioning support of the men who run the animal rights groups. They become groupies who seek approval through their comments, knowing that any criticism or critical thinking will be deleted.

ass ceilings of their workplaces, by working in fields traditionally dominated by men, by demanding equal pay for equal work; however, none of the advancements made by women have given them secure futures in their old age. They often have to leave work to be caregivers to family members, and lose both opportunities for advancement and robust pensions. When it comes to women animal rights activists, they continue to encounter men in most of the leadership roles, to inherit strategies for activism that were created by men and to operate in social movement structures that men continue to enforce. As women animal rights activists age, if they are visible at all they are many times type-cast as nurturing and lacking the youthful exuberance of the majority of movement members (Barnett, 2005). Their online involvement in activism is too often unquestioning support of the men who run the animal rights groups. They become groupies who seek approval through their comments, knowing that any criticism or critical thinking will be deleted.

It must also be mentioned that women are objectified in terms of their appearance on a daily basis. Saggy skin and wrinkles are treated as a problem that needs to be solved rather than a part of the aging process that has its own beauty. Gray hair is something to be avoided at all costs through expensive color treatments. Surgeries exist to remove varicose veins and veins running across women’s hands simply because society deems veins to be ugly. Age spots are the targets of countless lotions and potions, even laser treatments. It is hard enough for aging women to accept their own bodies and fight against societal stereotypes of the aging body without a logo for an animal rights group adding to this stereotype of aging women’s bodies.  GOV could easily become an exemplary leader in the animal rights movement by addressing the intersection of ageism and sexism. Why not name the group simply Grumpy Vegans? Why not find a logo that doesn’t socially reproduce the stereotypes of aging in our society? Surely in a group so concerned with a call to “reject exploitation and commodification” of animals they could reject the exploitation and commodification of aging women—and men—by finding some other name and logo to promote their group. Just as sports teams are rejecting names and logos that stereotype women, Native Americans and POC, rejecting ageism in the animal rights movement is an important next step. Just as the language of racism and actions like dressing in red or black-face are rejected, ageism in the animal rights movement must be rejected. Reject ageism.

GOV could easily become an exemplary leader in the animal rights movement by addressing the intersection of ageism and sexism. Why not name the group simply Grumpy Vegans? Why not find a logo that doesn’t socially reproduce the stereotypes of aging in our society? Surely in a group so concerned with a call to “reject exploitation and commodification” of animals they could reject the exploitation and commodification of aging women—and men—by finding some other name and logo to promote their group. Just as sports teams are rejecting names and logos that stereotype women, Native Americans and POC, rejecting ageism in the animal rights movement is an important next step. Just as the language of racism and actions like dressing in red or black-face are rejected, ageism in the animal rights movement must be rejected. Reject ageism.

References

Abolitionist, T. A. (2015, March 27). About this Project. Retrieved from The Academic Abolitionist Vegan: http://academicabolitionistvegan.blogspot.com/

Barnett, R. C. (2005). Ageism and Sexism in the Workplace. Generations, 25-30.

Lahey, J. N. (2006). Age, Women, and HIring: An Experimental Study. Chestnut Hill, MA: The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Dr. Martindill earned her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Missouri and taught there in the Sociology Department, the Peace Studies Program and the Women’s and Gender Studies Department. Her areas of emphasis include political sociology, organizations and work, and social inequalities. Dr. Martindill’s dissertation focuses on the no-kill shelter social movement and is based on ethnographical research conducted during several years of working in an animal shelter. She is vegan, a feminist and is currently interested in the stories women tell through their needlework, including crochet, counted cross stitch and quilting. It is important to note that Dr. Martindill consistently uses her academic title in order to inspire women and members of other marginalized groups to pursue their dreams no matter what challenges those dreams may entail, and certainly one of her goals is to see more women in academia.