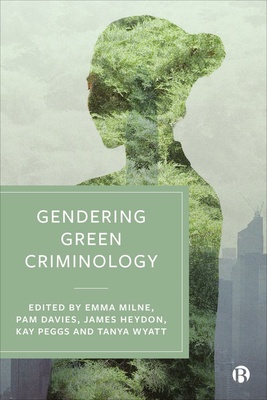

Although vegan feminism is a relatively new theory of social change in the West, it has had a rich background with a variety of innovative tactics, developed by innovative women in the resistance. In “Vegan Feminism Then and Now: Women’s Resistance to Legalised Speciesism across Three Waves of Activism” published in Gendering Green Criminology (Bristol University Press 2023), Lynda Korimboccus joins me in exploring this history through the efforts of three outstanding activists we take to represent feminist approaches to anti-speciesism across three primary waves of collective effort.

Charlotte Despard and First-Wave Intersectionality

The first, Charlotte Despard, was a British woman of Irish birth who was heavily active in Irish independence efforts, feminism, vegetarianism, and anti-vivisection campaigning. She is perhaps best remembered in the anti-speciesist movement for her protests involving the contentious Brown Dog statue in Battersea, London. The statue, meant as an homage to a canine who languished in the vivisection industry. This little dog represented thousands of others who were victimized by the increasingly powerful and entrenched medical science.

The statue was a direct challenge to patriarchal institutions and their systemic violence against Nonhuman Animals…and others. Despard chose Battersea for a reason: it was also a hotbed of Irish nationalism, feminism, and socialism. Despard’s protest tactics were intersectionally aware and explicitly engaged coordination across movements. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the belief in social progress was not isolated by cause. Many women activists were actively engaged in a variety of campaigns simultaneously, sometimes in overlapping ways.

Patty Mark and Second-Wave Open Rescue

By the mid-20th century, women had become the dominant group in activist ranks. And, although men’s philosophical contributions tended to take precedence, women activists were busy developing novel tactics for dismantling a now entrenched speciesist economics order. Patty Mark, for instance, had innovated a new strategy in Australia that both challenged the mundane normalcy of speciesism and physically intervened in Nonhuman Animal suffering. Her “open rescue” approach intentionally and strategically broke the law, the law being deemed illegitimate due to the horrific harms it protected. This tactic encouraged activists to peacefully enter industrial spaces to remove some victims to safety and disrupt industrial processes. Activists often chained themselves to facility infrastructure as well.

The aim was to attract media attention through illegality and disruption, bringing attention to the cause and allowing the public a rare opportunity to see within hidden speciesist spaces. Arrest was not only risked but even encouraged as it added to the spectacle and disruption. This tactic was innovative in introducing feminist ideals of nonviolence and active compassion.

Sarah Kistle and Third-Wave Vegan Intersectionality

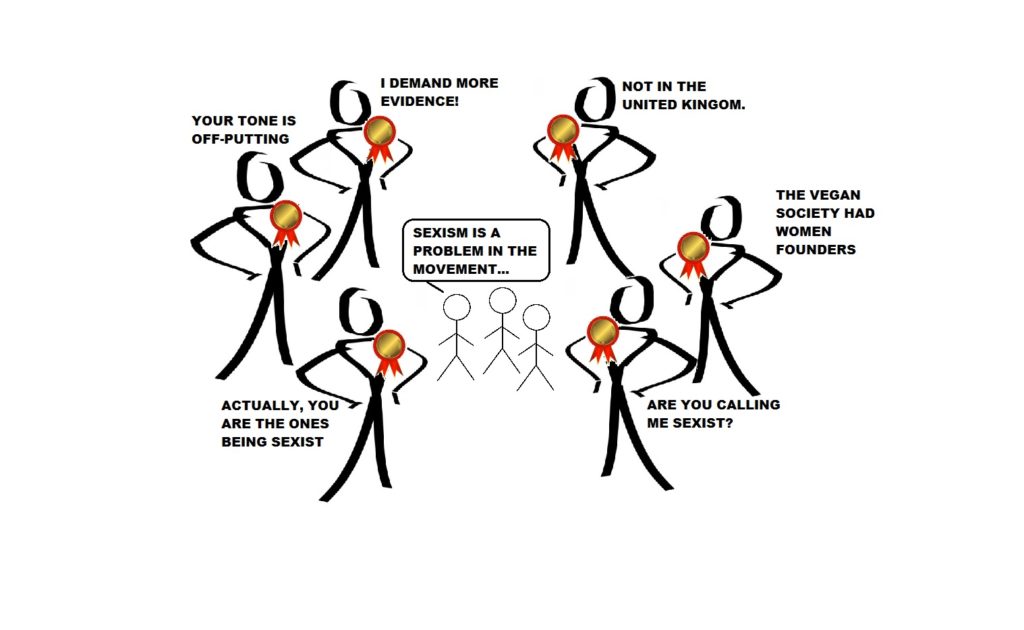

Finally, we explored the tactical developments of Sarah Kistle. As the movement entered the 21st century, a return to intersectionality seemed ever more necessary. The late 20th century had witnessed a considerable neoliberalization that introduced and reified individualist approaches to social change. Indeed, the rational ideology that underpinned this shift made feminist approaches appear marginal, deluded, and unfocused. This new era of “rational” activism had also normalized welfare reform and animals’ flesh “reductionism.”

Sarah Kistle became a prominent figure in the debates that would arise between these two positions by the 2010s. Kistle advocated for a radical, intersectional approach to advocacy, insisting that veganism was the least humans could do to alleviate speciesism, and the movement had a duty to promote it as such. Importantly, she argued that this vegan message should not be restricted only to “animal lovers,” but should be actively put into conversation with other social justice causes. As a Korean American, she recognized that the unjust experiences of Nonhuman Animals heavily entangle with that of marginalized human groups. With the outbreak of Black Lives Matter protests later that decade, she realized this vegan intersectional theory by opening a vegan restaurant in Minneapolis, employing Black Lives Matter activists who had been harassed and arrested by the police.

Across all waves, we can find so many inspiring stories of innovative women who fought a speciesist legal system to advance the radical idea that animals (and the humans whose experiences intertwine with that of other animals) matter. Indeed, Despard, Mark, and Kistle took on the police themselves, using state repression as a means to shine light on the personhood of the oppressed. It is a vegan feminist criminology that should inspire another generation of women to critically examine a criminal justice system that has historically relied on violence, control, incarceration, and the stripping of rights to maintain not only speciesism but many other systems of oppression. Future tactics might continue to test the limits of what is legal and what is legitimate, devising new modes of resistance to unjust state institutions of “justice.”

Read the full article here.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Kent. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She is the co-founder of the International Association of Vegan Sociologists. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and is a member of the Research Advisory Council of The Vegan Society. She has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute and has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Environmental Values, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis.

She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016), Piecemeal Protest: Animal Rights in the Age of Nonprofits (University of Michigan Press 2019), and Animals in Irish Society: Interspecies Oppression and Vegan Liberation in Britain’s First Colony (State University of New York Press 2021).

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.