Too often in the Nonhuman Animal rights movement sexist scripts are used to push messages of animal liberation. While utilizing the naked female form as a stand-in for other animals is a common tactic, there is a growing trend among some organizations to pull on more insidious themes in pornography to resonate with a sex-saturated society.

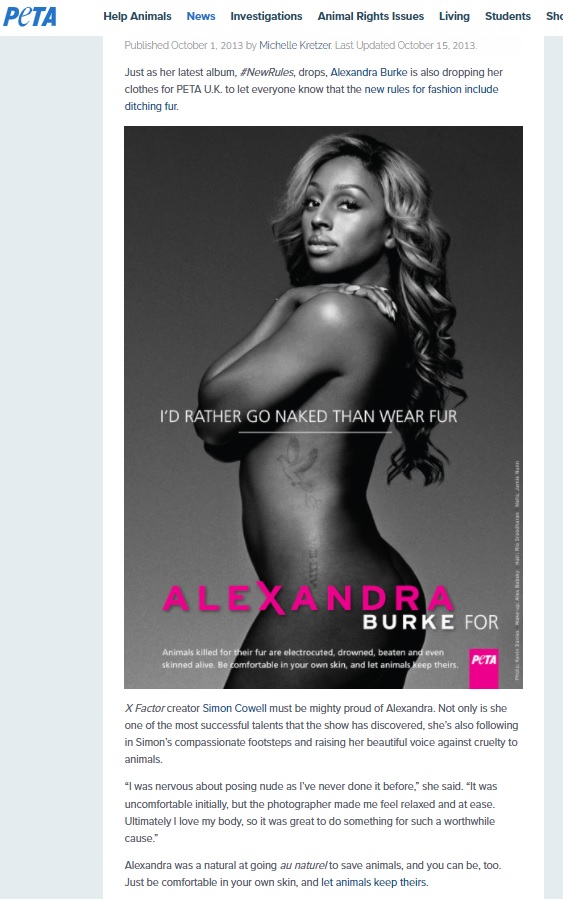

Consider the “I’d Rather Go Naked Than” ad campaign featuring Alexandra Burke. The advertisement itself is rather standard for PETA, but the promotional language is rather disturbing:

“I was nervous about posing nude as I’ve never done it before,” she said. “It was uncomfortable initially, but the photographer made me feel relaxed and at ease. Ultimately I love my body, so it was great to do something for such a worthwhile cause.”

As pornography becomes more normal in the public sphere, the scripts that used to tantalize are now tolerated. Producers have responded with increasingly shocking material. In the case of PETA, the “I’d Rather Go Naked Than” campaign that launched in the 1990s was initially quite shocking. However, naked women are now ubiquitous even in mainstream media. There is likely pressure to keep these campaigns relevant with more extreme and fetishistic framing.

In Burke’s case, the trope of the reluctant, innocent woman whose inner slut is waiting to emerge has been applied by PETA campaigners. This is not at all to slut-shame, but it is clear that the campaign’s language aligns with perhaps the most popular sexual script in pornography. It is found in the most viewed genres centering women and girls who are described as virgins, teens, or “barely legal.” Although she is clearly uninterested in a sexual exchange, she is persuaded to do so, and, after the act is complete, she indicates that she actually enjoyed participating.

This is a classic “no-means-yes” or “no-means-persuade me” myth that predators use to rationalize violence against women and pornographers use to shock consumers who have built up a tolerance. In both pornography and PETA campaigning, even if a man is not physically present in the scene, the power of the pornographer, media producer, and (patriarchal, male-owned) media, in general, is apparent in the ability to make the woman behave against her will.

Traditional gender norms teach us that women and girls are supposed to play “hard to get” and be innocent, pure, and unwilling. It is this unwillingness that is eroticized. Rape and sexual domination are exercises in power.

PETA emulates this common pornography trope to titillate, but this tactic comes at the expense of women’s dignity. Furthermore, it risks aggravating rape myths that endanger us all. If the Nonhuman Animal rights movement actively contributes to a culture of domination and violence, it is unclear how this will be effective for animal liberation.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Kent. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She is the co-founder of the International Association of Vegan Sociologists. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and is a member of the Research Advisory Council of The Vegan Society. She has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute and has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Environmental Values, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis.

She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016), Piecemeal Protest: Animal Rights in the Age of Nonprofits (University of Michigan Press 2019), and Animals in Irish Society: Interspecies Oppression and Vegan Liberation in Britain’s First Colony (State University of New York Press 2021).

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.