The abolitionist faction of the Nonhuman Animal rights movement is unique in the movement because it specifically values intersectionality. That is, abolitionist activists recognize that sexism, racism, heterosexism, and other isms are as morally problematic as speciesism. Indeed, many abolitionists recognize that these systemic discriminations are actually entangled and mutually reinforcing.

Intersectionality is not only applicable to general society, it has relevance within social movement spaces as well. The Nonhuman Animal rights movement is male-dominated with a female majority and sexism has been heavily documented. It is a movement that is also white-dominated with few activists of color offered platform or leadership and a notoriously racist past with regard to campaigning and claimsmaking. Acknowledging these connections in social justice efforts is so very important for counteracting oppression.

In a movement that opposes inequality but still evidences inequality in its interactions with activists and members of the public, a strange situation occurs in which inequality may persist unchecked amidst efforts to resist it. Following many years of social justice campaigning across several social movements, few would openly admit to being bigoted today. Most like to think of themselves as upstanding and moral. Similarly, in an era in which diversity is theoretically embraced as a social good, most people champion diversity. If most agree that bigotry is bad and diversity is a worthy goal, why the persistence of bigotry and exclusion?

Because discrimination is often hidden or abstracted through institutionalized practices, it becomes more difficult to identify. With discrimination hard to “see” (at least to those who benefit from it or who are otherwise not impacted by it), a disconnect between theory (philosophical support for social justice) and practice (physical support for social justice) emerges. Oppression is systematic, and, at least in the West, individualism makes it difficult to understand how each one of us is shaped by that system and how we, in turn, contribute to that system through passive (or active) compliance. Those who are relatively privileged may view themselves as allies against oppression, but will not always recognize responsibility for that oppression or personal benefit from it.

It gets even trickier in a social movement space in which activists actively embrace intersectionality theory and diversity goals. More than the average citizen, a social justice activist is personally invested in an anti-oppression identity. For some, this means regular interrogation of oppression in all its forms paired with active self-reflection. Being an ally is not easy, as it can require unlearning quite a lot of socialized norms and values, resisting entrenched social systems, and giving up privilege. It takes humility and a willingness to make mistakes and feel uncomfortable sometimes.

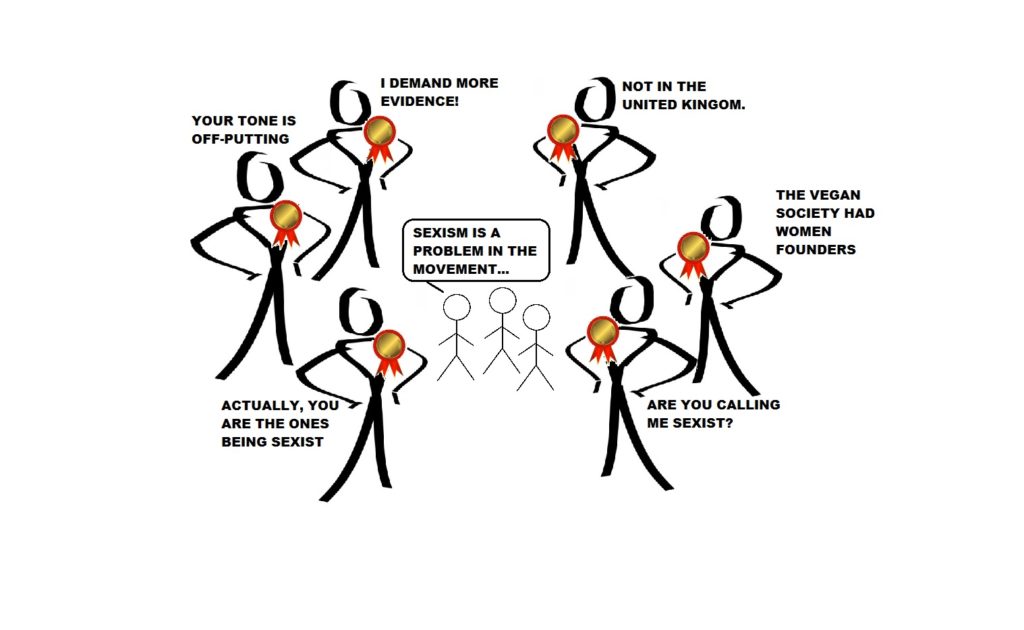

For many others, however, the intersectionality identity simply becomes a badge to be worn. Anyone can wear the badge, whether or not they actually do anything to earn it. Even worse, the badge can become a form of authority. With the badge brandished, it becomes difficult to challenge activists who engage in harmful or problematic practices. The badge can also create a psychological barrier for the wearer who may become less willing to acknowledge challenges as valid.

Unfortunately, this is a persistent issue in anti-speciesist spaces, including the abolitionist faction (despite its principled commitment to intersectionality). Privileged abolitionist vegans regularly flash their ally badges while simultaneously blocking intersectionality efforts. Some years ago, Sarah Kistle of The Abolitionist Vegan Society terms these persons “Badge-allies.” Badge-allies create another barrier to meaningful feminist discourse and complicate the possibility of implementing anti-oppression practice.

By way of some examples, women who have critiqued patriarchy in the movement have been accused of “misandry” and subjected to coordinated stalking and bullying campaigns. Women of color introducing conversations about race have been harassed and deplatformed, as their criticism of white supremacy is interpreted as “racist.” The majority of the accusers, bullies, harassers, and gatekeepers in these cases were white men (and many white women). Wielded in these ways, intersectionality becomes a strategic weapon for privileged people to protect their privilege and protect themselves from criticism.

These actions reflect an element of conscious discrimination, but they need not always be intentional. Microaggressions are also heavily used by Badge-allies. Again, few persons today see themselves as bigoted, but they can still engage in discrimination in unintended or unconscious ways. Microaggressions can include interruption, cat-calling, sexualizing, or desexualizing, misgendering, tone-policing, delivering or laughing at a sexist or racist joke, dismissing, downplaying or ignoring the experiences of a marginalized group, and denying the reality of sexism, racism, and other forms of oppression. Badge-allies are less likely to see microaggressions of this kind as aggressive or discriminatory because they have self-identified as intersectionally conscious.

Being an ally means more than simply wearing the identity like a badge. True allyship requires action and open dialogue with the marginalized groups that are being represented. Intersectionality is not a means for protecting privilege and shutting down critical discussions. It was developed as a philosophical tool for acknowledging a variety of experiences and how several core systems of inequality and mechanisms of oppression operate in similar, mutually supportive ways to shape those experiences. Intersectionality is a map for resistance, not a manual for maintaining a broken system.

An earlier version of this essay first appeared on The Abolitionist Activist Vegan blog on April 2, 2015.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Kent. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She is the co-founder of the International Association of Vegan Sociologists. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and is a member of the Research Advisory Council of The Vegan Society. She has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute and has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Environmental Values, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis.

She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016), Piecemeal Protest: Animal Rights in the Age of Nonprofits (University of Michigan Press 2019), and Animals in Irish Society: Interspecies Oppression and Vegan Liberation in Britain’s First Colony (State University of New York Press 2021).

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.