Content Warning: Discusses sexist, racist, ableist, and heterosexist language.

Not Safe For Work: Some offensive words are presented.

By Corey Lee Wrenn, M.S., A.B.D., Ph.D.

Language is a process that we begin to learn as children, but continue to refine as adults. Social justice advocates in particular are constantly reevaluating our language with the understanding that words are embedded in power structures. We can disrupt oppression by rejecting particular words or labels. We can create our own power in creating alternatives.

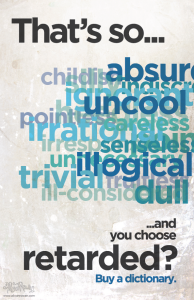

In my own case, this reevaluation began at sixteen. My friend told me that when I said, “That’s so gay,” it was hurtful to him. I stopped using it right then and there. When I got a little older, I realized what “That’s retarded” really meant: “This is so silly and ignorant it’s the equivalent of something that someone with an intellectual disability might say or do.” I stopped saying it. When I went vegan, I realized that calling people “chicken,” “cow,” “scaredy cat,” “rat,” etc. used Nonhuman Animals as objects of insult. I’ve started cutting back (I’m still a work in progress!). In my late 20s, as I started to find my feminist voice, I began to realize that “bitch” was no longer so easily articulated. It now makes me cringe. Fortunately, the “N word” has never crossed my lips.

Is this political correctness run amuck? Why do activists care so much?

Derogatory language has the power to uphold inequality. A lot of this language is either used by folks who are fully aware of the hurt behind it, or folks who are honestly unaware and have never stopped to consider the meaning of their words. Admittedly, the hold that language has over our brain makes it very difficult to eradicate many words, even when we are aware and want to change. Fair enough. However, when someone is presented with the reality of that hurt and the logic behind oppressive language, and they continue to dig their heels in, then we should find this problematic. At this point, it is no longer about ignorance. It’s about privilege.

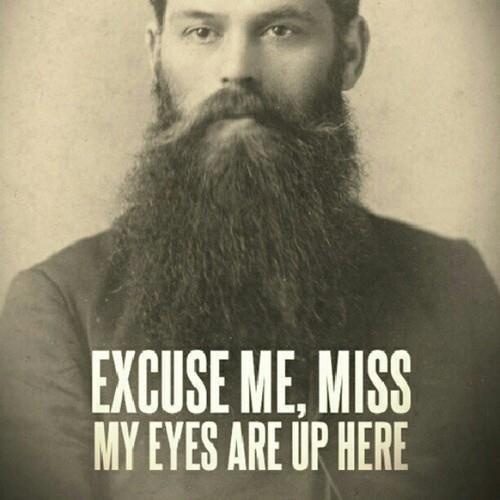

When I was visiting Scotland in 2012, my activist colleagues there had an ugly habit of calling any person they didn’t like a “twat.” After about the 100th time of hearing it, I finally said something. I explained that they were using a crass word for my genitalia as an insult. Basically being a female is lower; if they think something is bad, they insult it by calling it female. As punishment for making this objection, I was dragged into a 20 minute debate. It was me, the female-identified visitor, pitted against two British adult men who were convinced if they just explained to me what the word “really means” and that it “really means” nothing at all, it’s just something they say all the time, it’s always been that way, etc., then I’ll suddenly give up and realize the word isn’t sexist. And after all, don’t we use “dick” as an insult? The “men, too” argument is a common one that falsely imagines a post-gender utopia where men and women are represented equally and fairly.

In another example, an administrator for a Nonhuman Animal rights organization Vegans for Reason and Science adamantly defended the use of “stupid,” “insane,” “loons,” etc. as valid insults. I asked if they would ever use “faggot” or “gay” as an insult, they said absolutely not, and they would call it out if they ever heard it. I asked what was so different about using ableist language as slurs? Well, I was reading their words too literally, they explained.

The vulnerable groups in each situation may have varied, but there was one similarity between the people defending this language: their privilege. For the most part, I was up against men who were middle class, heterosexual, cis-gendered, non-disabled, and white-identified. This is the demographic that is granted the ability to create language and define meaning. Power is manifested and replicated through the construction of meaning and the validation (or invalidation) of others’ existence and their social worth.

People with privilege should not get to decide what language is or is not hurtful to vulnerable people. It shouldn’t matter how many gay friends or close female friends or sisters they have, or how long they’ve used the words, or how “figurative” they are meant to be. If someone in a disadvantaged position says they hurt, stop using them. These words are a product of ongoing discrimination and violence. Even if we do not condone the political meaning of these words, we have a responsibility not to be an active participant in the oppression of others.

Avoid using the identity of oppressed groups as an insult. There are about 171,000 words in the English Language; it won’t be a major inconvenience to retire a few. I recognize that these words are habitualized and continuously reinforced by our peers and pop culture, but we can do better if we try.

Ms. Wrenn is the founder of Vegan Feminist Network and also operates The Academic Abolitionist Vegan. She is an instructor of Sociology and graduate student at Colorado State University, council member with the Animals & Society Section of the American Sociological Association, and an advisory board member with the International Network for Social Studies on Vegetarianism and Veganism with the University of Vienna. In 2015, she was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory.

Ms. Wrenn is the founder of Vegan Feminist Network and also operates The Academic Abolitionist Vegan. She is an instructor of Sociology and graduate student at Colorado State University, council member with the Animals & Society Section of the American Sociological Association, and an advisory board member with the International Network for Social Studies on Vegetarianism and Veganism with the University of Vienna. In 2015, she was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory.