Content Warning: Discusses systemic sexism, online harassment, and misogynistic language.

Not Safe for Work: Contains coarse language.

| Editor’s Note: The author and I wish to make it clear that we do not endorse the notion that only cisgender women have vaginal canals, and we wish to acknowledge that some women do not have vaginal canals. We also acknowledge that intersex, transgender, agender, and other gender fluid persons can experience the sexism described in this essay. |

By Eve Christa Wetlaufer

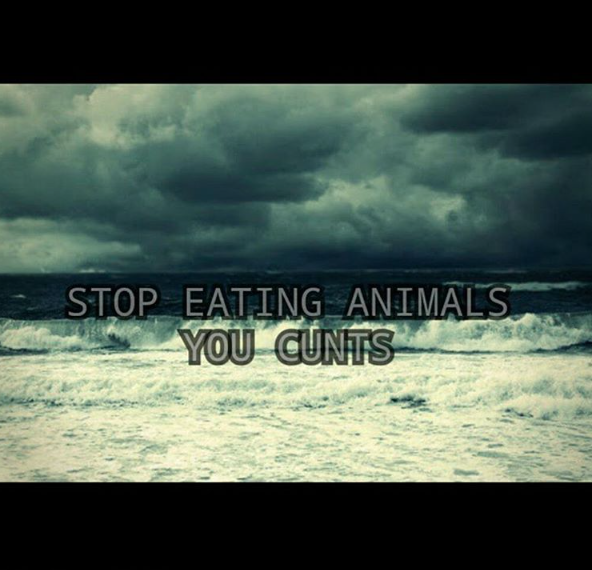

“STOP EATING ANIMALS YOU CUNTS.”

I did a double take. Did he really just use that word – and to promote veganism at that? Yes, he did, in a meme on his Instagram feed. A feed with 50,000 followers.

I was stunned and sickened, but sadly, not surprised.

In recent weeks, I have become increasingly aware of members within the vegan community casually using term “cunt” to refer to (and scold) non-vegans. I have seen it used in at least a dozen captions of pictures and comments on social media. Perhaps its most vigorous adherent is “vegan famous” YouTuber @Durianrider, who uses the term in his videos, which can get up to 65,000 views. The majority of the voices using this term have been straight white men.

Whenever I see the use of this word, I have responded by commenting my gut reaction. I explain that using this term to urge others to become vegan is both harmful towards people who identify as female, and also harmful towards the movement’s health and validity. I write that for a movement based on compassion for “all” animals, it is shocking to see what disregard there can be for the oppressions of human animals. I’ve also mentioned the recent article, “When is being vegan no longer about ethical living?” written by Ruby Hamad, in which she asserts:

Any vegan who thinks animal liberation can be achieved without addressing human oppression is kidding themselves.

And on one of the posts I wrote:

Yes, peace on Earth will be vegan – but it will also be a world free of racism, sexism, religious discrimination, ableism, ageism, etc.

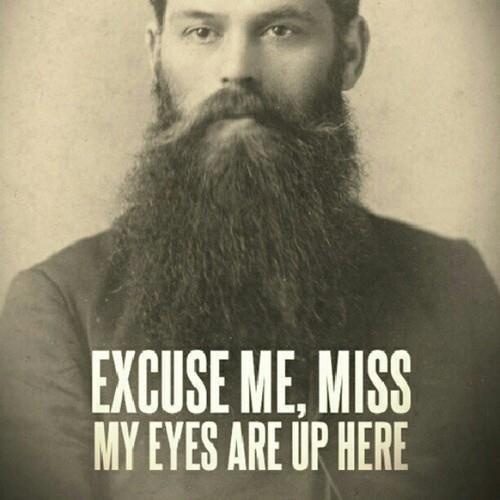

The response to my comments? Backlash – immediate and alarming. I was told to “Shut the fuck up.” I was told I was being “too soft,” that I was the “#funpolice,” “too politically correct,” and to “go cry somewhere else.” The supporters of using this term tried to silence me, and even questioned whether or not I was actually a vegan. As if a vegan would never point out inconsistencies within a movement – especially if the victim was a human! Especially if the victim was a woman.

After receiving these hateful comments, I did some research. Was I, in fact, over-reacting? I did a quick survey of the women in my house, and found that they too would be offended if called a “cunt.” My mother practically blanched at the question, and replied:

As far as I’m concerned, that’s the ultimate insult to a woman. You just don’t say it.

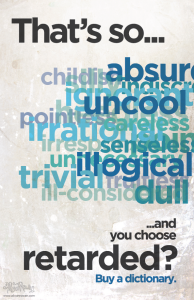

I then looked online and found that, interestingly, in England and Australia, “cunt” is generally used much more casually than in the United States, carrying much less of a sexist, derogatory stigma. Ok. But does that matter? Are we to forget the very real historical and contemporary uses of this term that have been, and still are, used to violate, denigrate and belittle those who identify as female?

I most certainly do not have all the answers, but I do understand that this topic is complicated. For instance, as a woman myself, I could feel empowered to use this term as to “reclaim” it, as different communities have done with words that have been used marginalized and oppressed them. I am also by no means speaking for all women, as I understand some are not offended by this word. But we cannot forget about those who are offended by it. We cannot call for liberation with words that do not further the liberation of other identity groups.

Since all ethical vegans want the world to go vegan, we need to start tailoring our language to be as effective and inclusive as possible, to make our mission based on love, on loving. If vegans really want to change the world, we need to stop using ethical eating to diminish or ignore other very real systems of oppression. It is also crucial for us to have the understanding that the vegan movement is just one puzzle piece in the greater movement for social justice. True social justice cannot be reached until all forms of oppression have been eradicated, and many of these injustices are linked. When we realize his struggles are her struggles, are their struggles are my struggles, the unity and support of each movement can propel us further into a more peaceful and just world.

The complex, gendered, and charged connotations with the term “cunt” should by no means be a part of the vocabulary of a movement comprised of individuals who preach compassion for animals. Changing the hearts, minds, and behaviors of non-vegans is crucial, but that also means investigating and changing our vocabulary at times. Although disagreements and conflicts within movements can potentially hinder the overall progress, it is important to constantly check ourselves and each other’s activism to make sure we are being as effective and compassionate as possible. So yes, I will continue to speak up when vegans use harmful words like “cunt,” and if you agree, I urge you to as well.

Eve Wetlaufer is in her third year at New York University in the Gallatin Program, with an individualized major investigating the historical human orientation toward animals, spirituality, and the environment, with a minor in the Animal Studies Initiative. Eve also holds a certification in plant-based nutrition from the T. Colin Campbell Center for Nutrition Studies. She has worked at several animal rescues, most recently Catskill Animal Sanctuary, as an Outreach and Education intern. She is also the loving companion to a rescued hound named Chrissy.

Eve Wetlaufer is in her third year at New York University in the Gallatin Program, with an individualized major investigating the historical human orientation toward animals, spirituality, and the environment, with a minor in the Animal Studies Initiative. Eve also holds a certification in plant-based nutrition from the T. Colin Campbell Center for Nutrition Studies. She has worked at several animal rescues, most recently Catskill Animal Sanctuary, as an Outreach and Education intern. She is also the loving companion to a rescued hound named Chrissy.