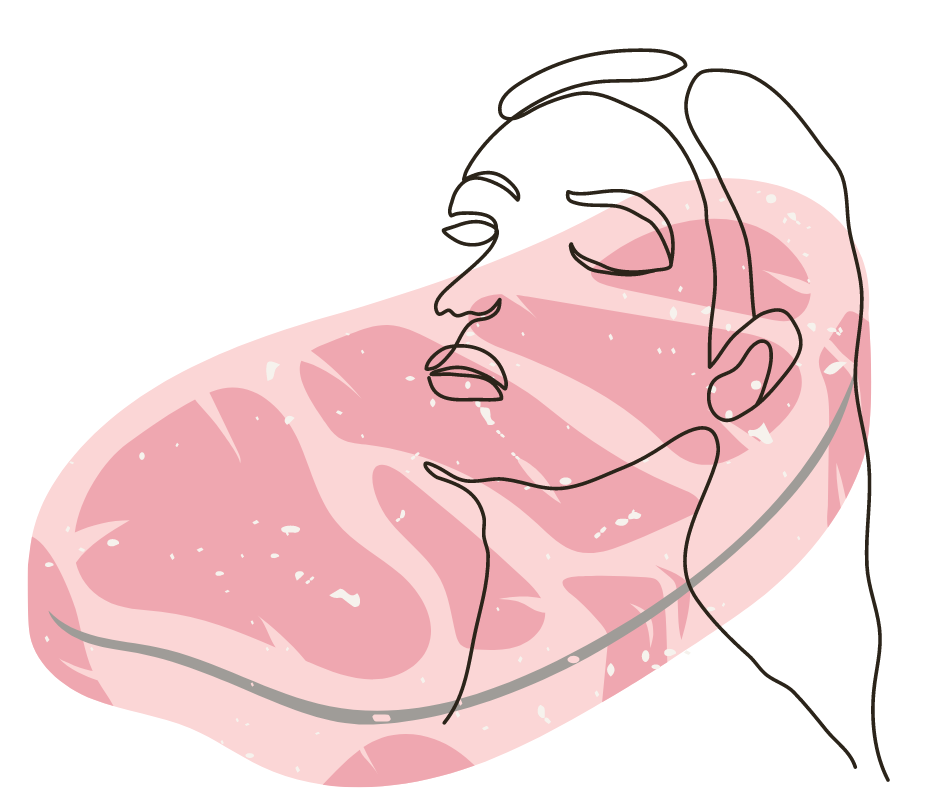

In my forthcoming book, Vegan Witchcraft, I explore the history of feminist witchcraft in the US and UK, arguing that, despite many key parallels, feminist witches have failed their commitments to other animals (often referred to as familiars) in either ignoring or outright rejecting veganism and total liberation.

That said, I have found evidence that some witches are making this connection. In the early 1990s, for instance, the Feminists for Animal Rights Newsletter announced the formation of a new sister group in New York, Witches for Animal Rights. Witches for Animal Rights rallied fellow witches by imploring them to “save the world with your fork.” Feminists for Animal Rights (1994) explains that “members worship the Goddess by promoting the wellbeing of her nonhuman animals” (16), suggesting that interested readers contact the Morningstar Coven in McDonough, New York. Witches for Animal Rights also surfaces in the record as a performing group in “No RIO,” an anti-gentrification guerrilla project in New York City that provided space and platform for radical artists and activists (Forte 1989). This organization was likely shortlived as I was unable to find futher reference.

In the 2010s, a the Protego Foundation formed from a group of Harry Potter fans who contextualize their anti-speciesist activism in the magical creations of J. K. Rowling. A registered nonprofit, the Protego Foundation “fights to end the abuse of the animals in the Muggle world through our inspiration from the magical creatures in the wizarding world […] empowering all magical persons to get active for animals.”

Gregory Maguire’s (1995) retelling of the “Wicked” witch of Oz sees her (Elphaba Thropp) as a social justice activist, advocating for Nonhuman Animals and the environment. Indeed, vegan scholar Christopher Sebastian (2020) suggests that her skin is green as a symbolic reference to her advocacy for nature and other animals, but also to mark her as a monstrous other in protesting the violent social stratification of Oz where the oppression of humans and other animals are explicitly entangled.

Witches for Animal Rights, Wicked, and the Protego Foundation are interesting examples of witchcraft engaged in the service of other animals, but they are exceptions, not the norm. Many feminists have embraced spirituality, paganism, and witchcraft as an important thealogical, philosophical, psychological, and even strategic means of resilience and resistence, but few extend this nature-based practice to include veganism and species-inclusiveness. It remains to be seen if modern witchcraft will, on a whole, begin to incorporate these values. To date, it is not sufficiently distinct from mainstream speciesist feminism and anthropocentric institutionalized religions.

References

Feminists for Animal Rights. 1994. “Resources.” Feminists for Animal Rights Newsletter 8 (1-2): 16.

Forte, S. 1989. “Guerilla Space: A Few Many Things about ABC No Rio.” X-posure Summer: no page.

Protego Foundation. No date. Who We Are. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from: https://www.protegofoundation.org/who-we-are.html.

Maguire, G. 1995. Wicked. New York: HarperCollins.

Sebastian, C. 2020. “Adaptation: No One Mourns the Wicked, But We Should.” Pp. 212-221, in The Edinburgh Companion to Vegan Literary Studies, L. Wright and E. Quinn (Eds.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Witches for Animal Rights. 1994. “Save the World with Your Fork!” Feminists for Animal Rights Newsletter 8 (1-2): 15.

Dr. Wrenn is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Kent. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She is the co-founder of the International Association of Vegan Sociologists. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and is a member of the Research Advisory Council of The Vegan Society. She has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute and has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Environmental Values, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis.