According to the Smithsonian, Benjamin Franklin, an inventor, gastronome, and “founding father” of the United States introduced tofu in the mid-18th century. Likely not having had any direct experience with the product himself, he only mentions it in a letter composed to a colleague. In the letter, he discusses his research of a Dominican friar’s account of Chinese cuisine with specific mention of “teu-fu” as an intriguing type of cheese.

One has to wonder why the huge population of Chinese immigrants might not be credited with this honor. The first wave began in 1815, and, surely, these folks would have brought knowledge of their own traditional foods. Unlike Franklin, they would have had a great familiarity with soy.

In any case, the efforts of a Chinese doctor can certainly be credited for an all-out campaign to introduce and popularize soy at the height of the first world war. The first Chinese woman to earn a medical degree in the US, Yamei Kin collaborated with the American government in its search for efficient and nutritious foodstuffs in a time of great scarcity.

Dr. Kin insisted that the US stood to greatly benefit from Chinese soy (and Chinese culture more broadly) and the many creative dishes it could render. She was also clear that the intense anti-Chinese sentiment of the era, coupled with imperialist stereotypes that characterized Asians as malnourished and weak, should be challenged. Indeed, she was quite aware that America’s qualms with the diet of the Chinese nation had much to do with nativism:

The chief reason why people can live so cheaply in China and yet produce for that nation a man [sic] power so tremendous that this country must pass an Exclusion act against them is that they eat beans instead of meat.

New York Times. 1917. “Woman Off to China as Government Agent to Study Soy Bean: Dr. Kin.” New York Times, June 10, p. 65.

Although she was raised in Japan and spent considerable time in the US, she was an ardent advocate of her native China. More specifically, she busied herself aiding girls and women of the country, making regular return trips in service to feminism.

Kin herself was not vegan, but she was certainly critical of meat and dairy. The world, she explained,

cannot very well afford to wait to grow animals in order to obtain the necessary percentage of protein. Waiting for an animal to become big enough to eat is a long proposition. First you feed grain to a cow, and, finally, you get a return in protein from milk and meat. A terribly high percentage of the energy is long in transit from grain to cow to a human being. […]

Instead of taking the long and expensive method of feeding grain to an animal until the animal is ready to be killed and eaten, in China we take a shortcut by eating the soy bean, which is protein, meat, and milk in itself.

New York Times. 1917. “Woman Off to China as Government Agent to Study Soy Bean: Dr. Kin.” New York Times, June 10, p. 65.

She sympathized a bit with the animals themselves. In an interview with St. Louis Post-Dispatch Sunday Magazine, she explains:

The trouble with vegetarians was that they expected us to eat such awful things. I’m not a vegetarian, but I must admit that I find great satisfaction in being able to sit down to most of my meals without facing the fact that I am eating slices of what was once a palpitating little animal, filled with the joy of life. I shouldn’t be surprised if the soy bean will save the lives of many American animals.

Kin developed tofu provisions for the war effort and successfully taste-tested them with soldiers. Unfortunately, logistical difficulties in procuring and transporting soy prevented its largescale adoption.

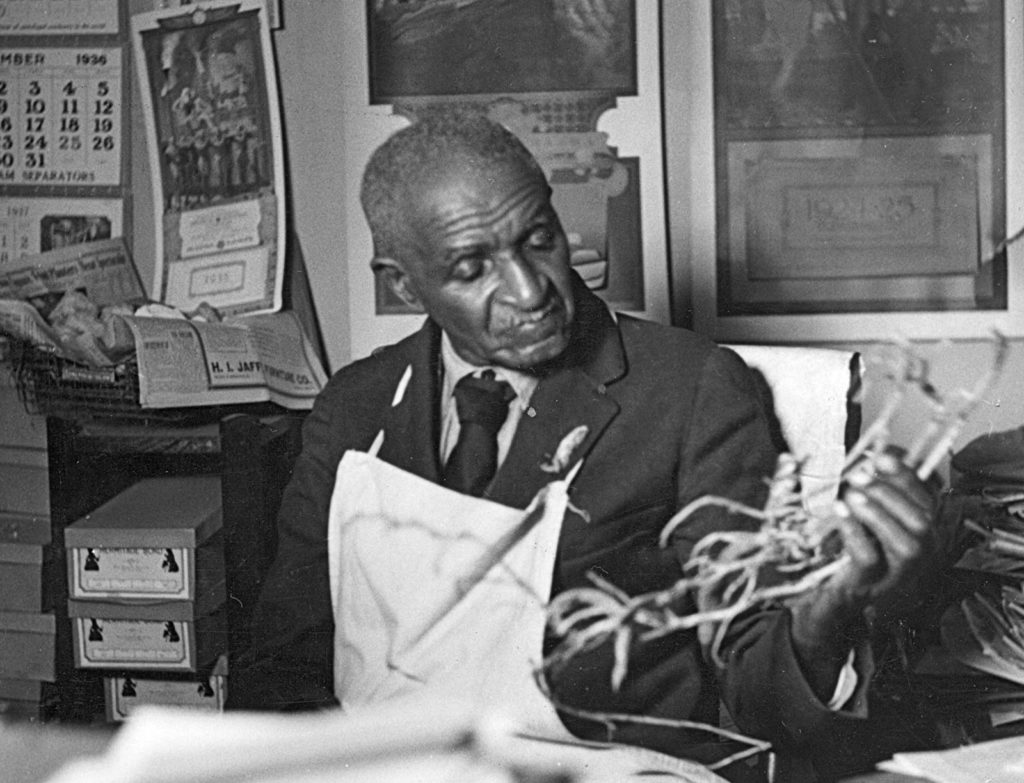

American experiments with soy as a potential savior of the nation’s nutrition would persist after the war. We also have George Washington Carver to thank for this. A scientist and food inventor who had been born into slavery, he is most often celebrated for popularizing the many ways to cook with peanuts. He did the very same with soybeans.

Tofu did not take off in American cuisine until the 1960s thanks to the hippie commune movement. Residents began making tofu (and soy milk) on-premises to feed the community. Some of these folks went on to start businesses as the commune movement came to an end and the back-to-the-land bohemians went back to their 9 to 5’s. The popularity of “natural foods” that persisted thereon catapulted soy into the American imagination, where it remains today.

It is a rocky love affair. Soy is increasingly vilified for its environmental impact, particularly when it is grown as a monoculture. However, the vast majority of soy that is produced today goes toward livestock feed, completely undermining the original vision of Kin and Carver. America’s hamburger culture, sadly, would come to prominence. The dream of a tofu nation populated by liberated animals and fortified humans would not fully materialize. Not yet, anyway.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Kent. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She is the co-founder of the International Association of Vegan Sociologists. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and is a member of the Research Advisory Council of The Vegan Society. She has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute and has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Environmental Values, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis.

She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016), Piecemeal Protest: Animal Rights in the Age of Nonprofits (University of Michigan Press 2019), and Animals in Irish Society: Interspecies Oppression and Vegan Liberation in Britain’s First Colony (State University of New York Press 2021).

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.