TRIGGER WARNING: Contains graphic descriptions of rape and violence against women and other animals.

NOT SAFE FOR WORK: Contains graphic sexual language and disturbing images of violated animals.

Vegan feminists argue that oppression is intersectional. In particular, the ways in which women are exploited and harmed are very similar to the ways in which other animals are. A shining example of this intersection is found in Fifty Shades of Chicken, a cookbook that parodies Fifty Shades of Grey (a best selling novel which glamorizes submissive sexuality and violence against women). Fifty Shades of Chicken, a book “for chicken lovers everywhere,” takes this disturbing subject matter to another level of degradation.

Throughout the book, a chicken’s body is used to replace that of a woman, and she is referred to as “Chicken” or “Miss Hen.” The choice of “chicken” was not accidental. Chickens eaten by humans are almost always female. The body parts of chickens (breasts, legs, thighs) are often applied to that of human women, and human women are often called “birds,” “chicks,” “chickens,” or “hens.”

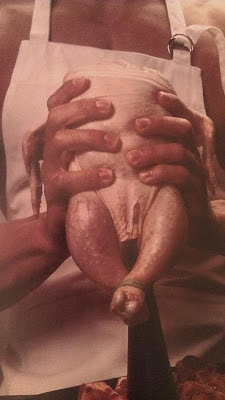

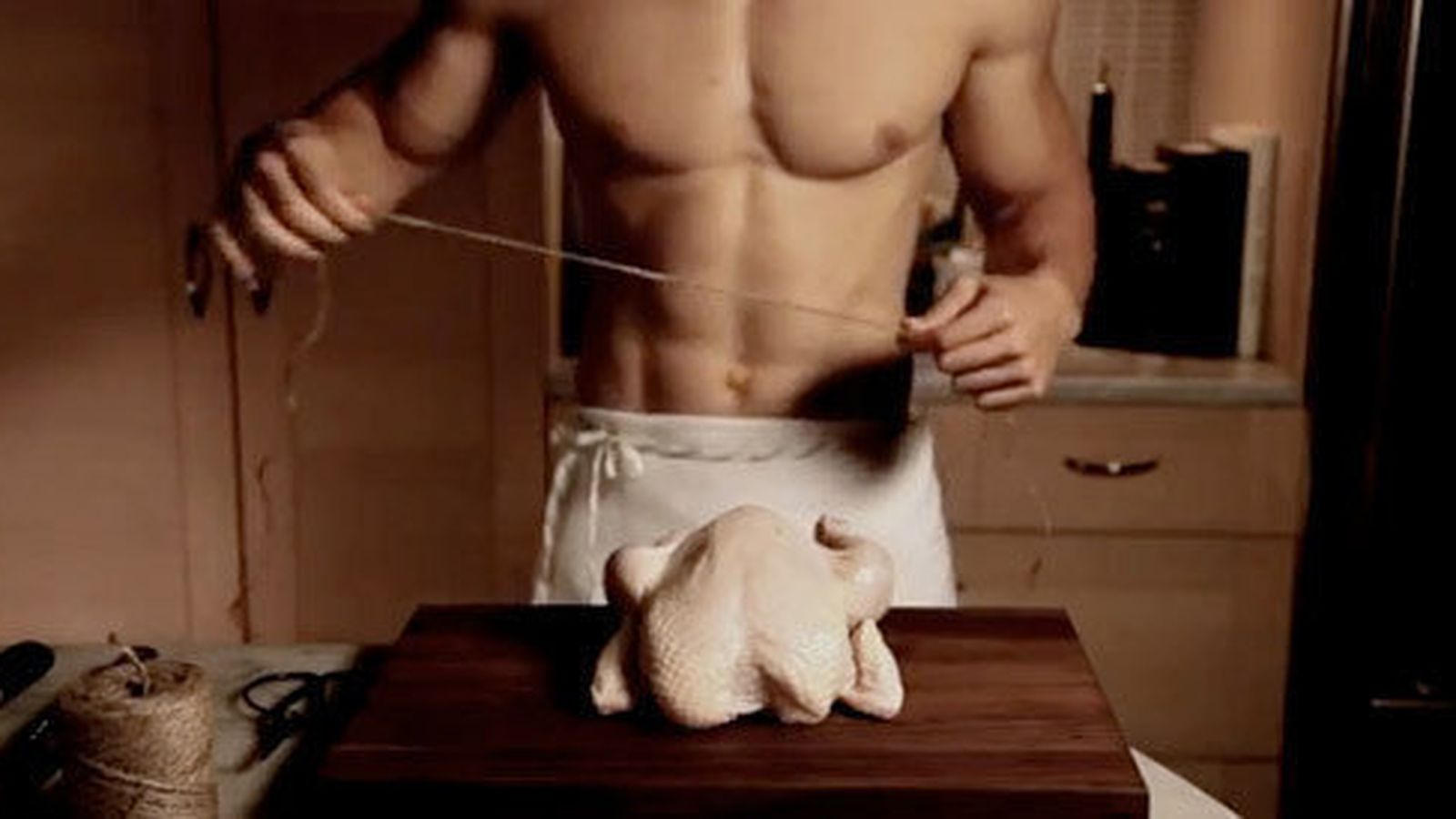

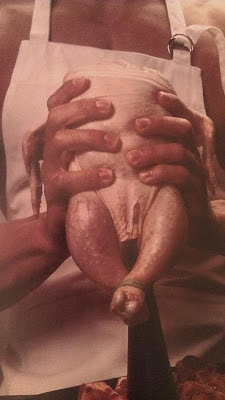

The cookbook features several images of a muscled, shirtless man dominating a chicken’s corpse with weapons, kitchen utensils, and binding (twine). In one image he is shown sodomizing her with an upright roasting device. In others, he is shown penetrating her with a baster and shoving cream into her bottom with his fingers. Most of the photographs of the finished “product” show the bird’s body splayed and ravaged. She is posed pornographically to mimic a defiled human woman.

The chef known as “Blades” sodomizes “Miss Hen” with the “erect member” of a vertical roaster.

The recipe titles are also disturbing:

- “Popped-Cherry Pullet”

- “Extra-Virgin Chicken”

- “Please Don’t Stop Chicken”

- “Jerked Around Chicken”

- “Mustard Spanked Chicken”

- “Cream-Slicked Chick”

- “Chile-Lashed Fricassee”

- “Skewered Chicken”

- “Steamy White Meat”

- “Bacon Bound Wings”

- “Dripping Thighs”

- “Thighs Spread Wide”

- “Chicken Thighs Stirred Up and Fried Hard”

- “Red Cheeks”

- “Pound Me Tender”

And my favorite:

- “Hog-Tied and Porked Chicken”

It is a regular smorgasbord of entangled oppression, violence, sexism, and speciesism.

These recipes are inextricably representative of rape culture. Sexualized violence is presented as normative, the female body is objectified as a passive recipient of male desire and aggression, and the obligatory obsession with virginity and female purity is highlighted.

Chapter Two, “Chicken Parts and Bits,” literally reenacts the fragmentation of the female body into consumable pieces which are wholly divorced from the person they once belonged to. This objectification erases personhood and makes exploitative consumption all the more palatable.

The recipe instructions also entail graphic violence, domination, and control:

Much pleasure and satisfaction is to be had from tying up your bird. Not only does it show your chicken who’s boss, but a tight binding ensures the chicken cooks exactly how you want it–evenly, moist, and tender. It also closes off the chicken’s cavity, so the juices swelling within can’t spill out, at least not until you’re ready for them. (p. 34)

Using large, strong kitchen shears and a confident hand, forcefully cut the backbone out of the chicken; first cut along one side of the backbone, then cut along the other side until it releases, then pull it out. Gently spread the bird open, pressing down on the breast to flatten it (see Learning the Ropes). Massage the flesh with 1 1/2 teaspoon of salt. (p. 116)

Position the chicken’s nether parts over the vertical roaster’s erect member and thrust the bird down. Tuck her wing tips up behind her wings, behind her body. Tie her legs together with a piece of butcher’s twine or cooking bands […] (p. 120)

It reads like a manual for serial killing.

Several gruesome pornographic narratives were included to preface the recipes and work the reader up into a hot bother for the pleasurable consumption awaiting them. Take this example from “Backdoor Beer-Can Chicken”:

‘Hush,’ he says. He smile and holds up a beer can.

‘Yes, baby, have a drink, I’m sure you need it.’

‘Oh, no, this is not for me, Chicken.’ He quirks his mouth into a wicked smile.

Holy f***…Will it? How?

I gasp as he fills me with its astonishing girth. The feeling of fullness is overpowering.

He rests me on the grill and I can feel the entire world start to engorge. Desire explodes in my cavity like a hand grenade. (p. 137)

Or this story from “Flattered Breasts”:

Suddenly he seizes me and lays me out on the counter, claiming me hungrily. His fingers pull me taut, the palms of his hands grinding my soft white meat into the hard granite, trapping me. I feel him. His stomach growls, and my mind spins as I acknowledge his craving for me.

‘Why must you always challenge me?’ he murmurs breathlessly.

‘Because I can.’ My pulse throbs painfully.

He grabs a fistful of kosher salt.

‘I’m going to season you now.’

‘Yes.’ My voice is low and heated.

He reaches for a rolling pin, then hesitates, looking at me.

‘Yes, please, Chef,’ I moan.

The first blow of the rolling pin jolts me but leaves behind a delicious warm feeling.

‘I. Will. Make. You. Mine.’ he says between blows. (p. 62)

These narratives often present the chicken’s corpse as a willing accomplice. This is quite telling, given that she was beheaded and drained of blood days before she arrived in this man’s kitchen under saran wrap. This narrative of willingness is ubiquitous in rape cases and pornography. Even girls and women who are drugged or unconscious are frequently considered “willing.” It is therefore not surprising that a decapitated corpse, in the case of Miss Hen, is depicted as consenting.

As with other females, Miss Hen’s sexuality is strictly controlled and meant only for male entitlement. The relationship of domination that makes consent an impossibility, privileges men, and leaves women and Nonhuman Animals in a position of subservience is obscured. Instead, this chicken is “free-range,” implying that she has a choice in the matter.

What is worse, these actions are supposedly done out of “love” and for her pleasure. It is not enough that women and Nonhuman Animals submit to male superiority, they must also be seen as enjoying their subjugation. If the consumer was made aware of the immense suffering that lies beneath the surface of pornography, prostitution, exotic dancing, dairy, “meat,” “leather,” zoos, horse racing etc., the pleasure of that consumption would be challenged. Previously unexamined oppression would come to light. What a buzz kill.

This book takes the male fantasy of ultimate control over a humiliated, submissive woman to its full fruition. Men cannot legally coerce women into obliging sex slaves through force and fear. They cannot legally fragment women into their body parts, strip them of their identity and self-efficacy, or pulverize and consume their bodies for sexual gratification (though more men than we like to admit do). However, men can have the next best thing–they can humiliate, torture, dismember, and objectify a female Nonhuman Animal for pleasure. He can molest her, sodomize her, rape her, bind her, break her, “pork” her, and “slick” her with cream to the point of physical arousal and salivation.

Whether the victim is human or nonhuman, the script is the same. Control over the vulnerable is sexualized; domination and power is hot stuff. And it’s completely legal, with full support from a patriarchal society.

He continues to fondle my liver with his fingertips until I can’t stand it.

He gently places my quivering offal into a skillet where some softened onions are waiting for me. Holy f****** s***…we’re cooking in the middle of a party? Everyone’s mingling and chatting, but I am not paying attention. He stirs my insides with a deft wooden spoon, around and around [ . . . ] (p. 103)

As traumatizing as this book is on its own, what is perhaps most upsetting is the complete lack of criticism from the general public. The book racks up rave reviews by Amazon users who are beside themselves with laughter, folks who can’t get over just how darn clever this book is. Violence against women and Nonhuman Animals is often trivialized, masked by humor, downplayed, and made more or less invisible…but surely, the triggering offensiveness of this book could not be ignored? Not so. At the time of this writing, Fifty Shades of Chicken enjoys a whopping 5 out of 5 stars on Amazon.

The message could not be clearer:

Women=Nonhuman Animals=Sexualized=Dominated=Meat=Objects of Pleasurable Consumption

and

Nonhuman Animals=Feminized=Sexualized=Dominated=Meat=Objects of Pleasurable Consumption

. . . and apparently this is a hoot.

An adaption of this essay was published in 2013 in Relations: Beyond Anthropocentrism 2 (1): 135-139.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology and past Director of Gender Studies (2016-2018) with Monmouth University. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology and past Director of Gender Studies (2016-2018) with Monmouth University. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).