Who was Victoria Woodhull?

Victoria Woodhull (1838-1927) was, in the late 19th century, one of the most outspoken and well-known women’s rights advocates. More than a feminist, she was also abreast of many other social justice causes of the era, including child welfare, food reform, and wealth redistribution. Many secondary sources hint that Woodhull had ties to vegetarianism (Donovan 1990, Robinson 2010), suggesting a potentially lost hero overlooked in the vegan feminist annals.

A survivor of child marriage, Woodhull advocated for the radicalization of oppressive marriage institutions and found herself dubbed “Mrs. Satan” for her radical “free-love” politics. Indeed, her influence (or at least tenacity) was so great, she was compelled to run for presidency under the Equal Rights Party in 1872.1 She believed in the human capacity to challenge injustice and progress society, but this position tended to reflect the eugenics discourse that was popular at the time. Indeed, Woodhull’s politics were premised on the supposed social and biological malleability of society:

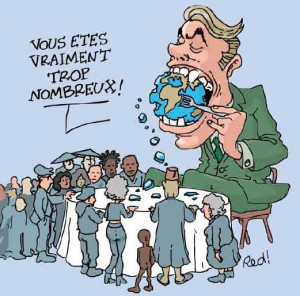

Social evils are caused, first, by unequal distribution of wealth–no one held morally responsible as regards the methods by which the wealth is acquired; second, too many individuals are over-fed and underworked, and too many are overworked and underfed; third, too many are badly bred.

(Woodhull 1892a: 53)

She adopted a Christian scientific approach, deeply contemplating the animality of human beings and how moral concern for others as well as the cultural advantages of civilization differentiated the species. While such a perspective could certainly be said to diminish other animals who are positioned as morally and culturally stunted by comparison, her aim was to wield modern scientific and ethical advancements to better society (Woodhull 1893). For Woodhull, attention to the possibilities of optimum human intellect and social organization was needed, as slavery, marriage, capitalist exploitation, and other institutionalized inequalities were thought to stifle human progress itself.

For these reasons, Woodhull actually saw herself as a contemporary of Marx. I suspect that, vegetarianism, if included in her ideology, would certainly be positioned in line with her vision for social revolution. I examined some of Woodhull’s work in hopes of uncovering this possible intersection.

The results were disappointing to say the least.

Eugenics, Animality and Social Change

Woodhull’s politics are documented in the pages of her publications, namely the Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly and The Humanitarian. Indeed, her journal would be the first to print Marx and Engel’s Communist Manifesto in the United States (Johnston 1967). These journals are also reported to feature discussions of vegetarianism. Woodhull had been very successful in the stock market (another feminist first), allowing her to self publish. Her writings are subsequently deeply polemical.

For instance, despite her dedication to socialism, Woodhull’s idea of progress did not bode well for society’s marginalized social classes. In one editorial, she refers to these people as “totally usless [sic] animal weeds” who “choke and sap the vitality of the fit” (1893: 53). She argued that humans, like “horses and roses,” should be bred for betterment, as “progress in evolution is accomplished by the elimination of the unfit” (1893: 52).

Thus, challenging inequality was not just important as a moral matter to those experiencing it, but to society as a whole since social inequality made it difficult to determine who was “fit” or “unfit,” blocking “human progress” (1893: 52): “What wonderful solicitude is shown in the breeding of choice animals, and what utter indifference in the breeding of boys and girls, whereas it ought to be the other way” (1893: 52). I did not read closely enough to determine how she planned to execute this genetic policing.

Perhaps we can grant that the intentions of many eugenicists, particularly those who were ardent social justice advocates like Woodhull, were well-meaning. Disability politics of the late 20th and early 21st century, afterall, are comparatively postmodern in substance, questioning what constitutes “good,” “bad,” or “progress,” upsetting old binaries, and advocating for the radical and compassionate accommodation of all individuals just as they are. These ideas, I can only assume, were not well known at the time or at least failed to resonate given the heavy excitement surrounding cutting edge evolutionary science. The late 19th century was truly emboldened by Darwinism, which instigated a dramatic shift in Western epistemology. It seemed increasingly possible that humans were not just divinely appointed on earth by some unknowable, uncontrollable power that relinquished little control over society’s trajectory. Life on earth instead came to be seen as a work in progress, a work that might be adjusted through human agency.

That said, the particular vitriol of Woodhull’s position on persons relegated to the lower classes, people with disabilities, people with alcohol addiction, and even sex workers leaves little room for grace.

Vegetarianism, Animal Rights, and Humanitarianism

Woodhull’s attachment to eugenics is extremely disquieting, and, given her ardent interest in controlling bodies–human or nonhuman–to achieve her idea of social and biological perfection, I held out little hope that her vegetarian position would offer any redemption as I continued through her periodicals. In fact, in my precursory search of Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly (published in the 1870s) and The Humanitarian (published in the 1890s), I was not able to find any promotion of vegetarianism.2 Woodhull’s own writing dominated the periodicals, and primarily made mention of other animals for the purposes of comparison with humans who she believed ought to practice restraint and civility to distinguish themselves as a higher species. Domestication, with its manipulation of nonhuman bodies, was a point of inspiration for her eugenics agenda (Woodhull 1892b).

Dietary pieces were sometimes featured but did not advocate vegetarianism that I could see. A typical example can be found in a submission she published under the “Medical Department” of The Humanitarian, within which the author discusses ways to cure and process animal bodies for optimal consumption (Welles 1893a). In another article, the same physician rejects vegetarianism, as “the teeth of man” are “adapted to the mastication of animal flesh” and “animal food, thence, reorganized, furnishes immediately to man that highly organized and stimulating nerve food, from which the higher and nobler development of brain power is the manifest result” (Welles 1893b: 45). He goes on to justify human “supremacy over other animal life” by drawing on Innuit people of the Arctic and other Indigenous communities of the Americas as evidence to the supposedly natural (read primitive) way of the human species. Oppressing other animals is, on one hand, offered as evidence to the advancement of human civilization, while, on the other hand, the “uncivilized” peoples of the world who oppress animals (usually living in extreme environments and themselves deeply oppressed by European colonialism) are made examples of authentic humanity. The same weak (and colonialist) logics that stand in opposition to veganism today, in sum, are touted in Woodhull’s Humanitarian periodical.3

Her use of the term “humanitarian” is telling here. By the late 1870s, Woodhull was living in the southwestern United Kingdom, where the periodical was published and circulated. She was a contemporary of Henry Salt (who also lived in southern England) and would surely have been familiar with his own humanitarian writings and activism. Salt’s (1892) Animals’ Rights Considered in Relation to Social Progress was one of the first major publications on the topic of anti-speciesism. His own Humanitarian League (now the League Against Cruel Sports) centered the Nonhuman Animal cause in its agenda. Woodhull (1892a), by contrast, makes no mention of them at all in introducing her otherwise intersectional humanitarian platform as presidential candidate.4

It seems very likely that Woodhull, a socialist-feminist humanitarian active in the same region as Salt and a multitude of other socialist-feminist anti-speciesists, would have been familiar with their political claimsmaking.

“Humanitarian” Vivisection

Further evidence of Woodhull’s well-rounded speciesism can be found in another socialist article printed in The Humanitarian which explores the science of physical labor and its impact on the body. The evidence presented undoubtedly derives from vivisection. Woodhull anticipates criticism from her readers, including a quote from prominent vivisection-defending physician William Gull5 at the end of the article:

Sir William Gull was asked by a lady if he did not consider experiments on animals as cruel. “madam,” he said, “there is no cruelty comparable to ignorance.”

(Woodhull 1892: 39)

Of course, experiments that transpired in Victorian vivisection theaters and laboratories are the epitome of cruelty, enacted for the most wonton of curiosities without anaesthesia or any other alleviation from fear or pain. These are just the sort of cruelties that surely lurk behind the labor study that Woodhull spotlights in The Humanitarian, seeing as how it aims to understand the detrimental impacts of extreme distress on muscular and cardiovascular systems. Nonhuman Animals are inevitably slated for dangerous and gratuitous experiments such as these.6

Another case of vivisection is spotlighted in support of prison reform. One contributor recounts his travels abroad in Corsica, where he and his travel party killed several pigs to dissect for the purpose of learning more about their eating habits. Apparently, pigs, being opportunists, will eat all manner of things and persons, including deers, birds, other pigs, and even humans. This research is supposed to serve as a rudimentary criminology, explaining why criminals might engage in violent, seemingly unnatural crimes as do pigs (Rothery 1892). Whatever might be gleaned from the stomach contents of murdered pigs and bizarre trans-species comparisons of moral intent, it certainly does not support the notion that Woodhull was accommodating to vegetarian politics.

Conclusion

I want to be clear that my analysis of Woodhull’s writings is anything but comprehensive. It is based on a cursory and purposive sample of convenience. It may be the case that pro-vegetarian or anti-speciesist essays exist beyond the handful of digitized copies available to me, but it is quite clear that Woodhull’s first political interest is the sexual liberation of women, and her second is improving the moral and physical character of society through eugenics. Nonhuman Animals only surface as points of comparison, “nourishing” ingredients in food, and objects for scientific experiments. Nonhuman Animals, in other words, are merely fodder for her vision of a progressive society. The view that other animals are sentient beings capable of suffering and worthy of political action–a view that was widely adopted by other progressive era activists, especially suffragettes–was not adopted by Woodhull.

Ultimately, Woodhull’s campaign to include women in the 14th amendment to the US Constitution, the amendment that granted suffrage to recently enslaved African American men, sat uneasy with many fellow activists.7 Her insistence on free love—which prioritized women’s autonomy over men’s institutional and personal entitlement to them—sat even uneasier. Her politics were indeed so radical that she was eventually dropped by the American feminist movement, unsupported in her time but also unrecorded in their feminist anthologies and thus forgotten in modern women’s history. Even Marx found Woodhull’s socialist campaigning noxious and disingenuous. Unfortunately, if there were to be any redeeming qualities to be found in her support of vegetarianism, I have yet to find them.

Perhaps some elements of Woodhull’s tireless work to advance society is worth celebrating, particularly her effort to uplift women’s independence and her challenge the bondage of marriage. But her class position created a very awkward sort of sympathy with disadvantaged people that demeaned them as much as it hoped to uplift them. I suspect it is the same classist hierarchical thinking that leaves Woodhull unable to offer Nonhuman Animals any sympathy at all.

Notes

- Woodhull is considered by many to be the first woman to run for president, however she would have been too young to legitimately take office in the event of her election. Furthermore, her appointed running mate Frederick Douglass was likely unaware that he had been added to her ballot, suggesting the campaign was only symbolic.

- The Woodhull & Claflin Weekly is available through the Hamilton College Library. I browsed a few issues manually for mention of anti-speciesism or vegetarianism, but I also used a key word search for “vegetarian” which did not turn up any matches. Some issues of The Humanitarian are hosted online by The International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals.

- See Benny Malone’s How to Argue with Vegans (2021) and Ed Winters’ How to Argue with a Meat-Eater (2023).

- Woodhull’s platform, does, however, heavily emphasize the importance of providing substantive, healthy, and unadulterated food.

- Gull’s grim and uncompromising defense of vivisection has been cited as evidence by several web sources as to why this physician is thought a suspect in the “Jack the Ripper” case by some.

- Vulnerable humans were often exploited for vivisection as well, including people with disabilities, women, enslaved people, Irish immigrants, and people in poverty. It does not seem clear that Woodhull was aware of this important intersection in her support of vivisection.

- Some activists were concerned that introducing women to the proposal would be considered too radical by legislators and thereby undermine its potential to pass. Given that many advocating the inclusion of women were wealthy white women whose experiences were miles away from that of recently enslaved Black men, their insistence on inclusion, while merited, inflamed racial tensions in both feminist and abolitionist movements.

Works Cited

Donovan, J. 1990. “Animal Rights and Feminist Theory.” Signs 15 (2): 350-375.

Johnston, J. 1967. Mrs. Satan: The Incredible Saga of Victoria Woodhull. London: Macmillan.

Robinson, S. 2010. “Victoria Woodhull-Martin and The Humanitarian (1892-1901): Feminism and Eugencs at the Fin de Siecle.” Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies 6 (2).

Salt, H. 1892. Animals’ Rights Considered in Relation to Social Progress. London: Macmillan & Co.

Rothery, G. 1892. “The Unlikely Human.” The Humanitarian 1 (4): 65-68.

Welles, C. 1893a. “Practical Dietetics.” The Humanitarian 2 (5): 69-70.

Welles, C. 1893b. “The Habits of Health: Food.” The Humanitarian 2 (3): 45-46.

Woodhull, V. 1892a. “The Humanitarian Platform.” 1 (4): The Humanitarian 54-58.

Woodhull, V. 1892b. “Pedigree Farming.” The Humanitarian 1 (2): 25.

Woodhull, V. 1892c. “The Standard Value of Labor.” 1 (3): The Humanitarian 38-39.

Woodhull, V. 1893. “Address by Victoria C. Woodhull (Mrs. John Biddulph Martin), at St. James’s Hall, Piccadilly, 24th March, 1893.” The Humanitarian 2 (4): 49-55.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Kent. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She is the co-founder of the International Association of Vegan Sociologists. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and is a member of the Research Advisory Council of The Vegan Society. She has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute and has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Environmental Values, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis.