Too frequently in anti-speciesism advocacy, women become stand-ins for Nonhuman Animals suffering from extreme human violence and degradation. It is not by chance that women predominate in these roles. Women are selected (or self-select) because it culturally “makes sense” to audiences that sexualized violence will be aimed at women. If men, a relatively privileged group, were to substitute the vulnerable and suffering Nonhuman Animals, it just wouldn’t compute.

Women are regularly subject to violence and degradation, so they become the “natural” choice when staffing campaigns. Women in the audience, too, are familiar with the normalcy of misogyny, and perhaps social movements hope to trigger them into supporting the cause by tapping into their fears and traumas. Such a tactic begs the question as to how aggravating inequality for women could reduce inequality for other animals.

Consider the vegan advocacy film, The Herd. Status quo misogyny predominates, and there is arguably nothing that sets this film apart from standard sexist and violent horror movies except the good intentions of the filmmakers. The script is exactly the same: young, thin, white women, naked or nearly naked, are sexually brutalized for the titillation of the audience.

https://vimeo.com/119688523

I ask activists to consider how replicating violent, misogynistic media could, logistically, disrupt oppressive thinking about other vulnerable demographics. Further, I believe it is ethically problematic to contribute to a culture of woman-hating in a world where actual violence against actual women continues to happen so frequently that it can only be described as normal. Images have power, and these images should be used responsibly in service of social justice. It is both unwise and immoral to capitalize on sexism to advance anti-speciesism.

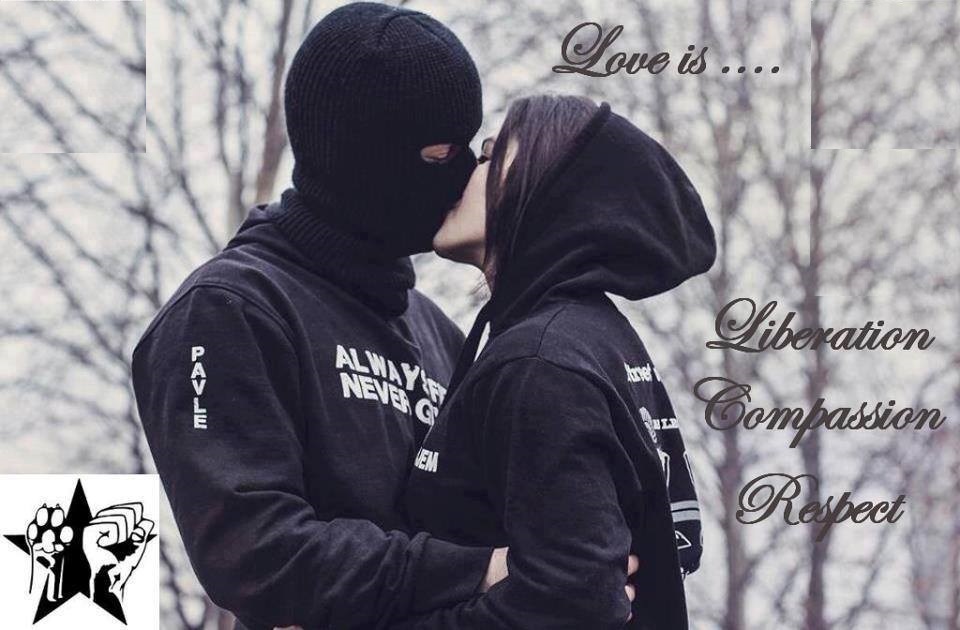

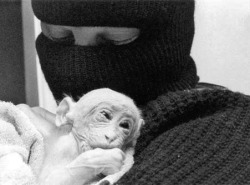

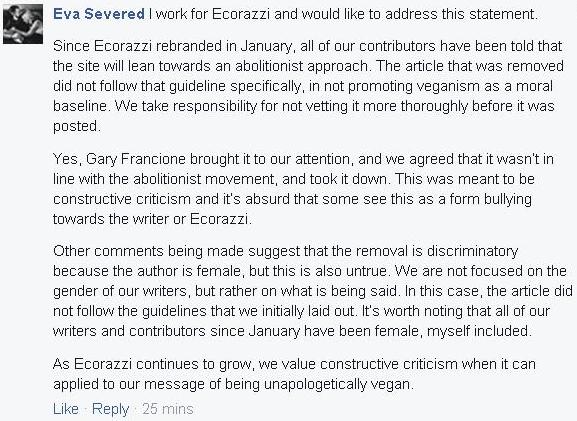

In the video linked below, I have compiled a number of images to illustrate the woman as sexy dying animal trope. This is a pattern that extends across a number of organizations, notably PETA, but also LUSH Cosmetics, 269life, and others. Consider what it means when activists instinctively position women as representatives of speciesist violence. Consider also the privilege afforded to men who are less frequently used, but also the dangers in positioning them as abusers in protest scenarios. In a society where violence against women is still not taken seriously, it is unclear how movement audiences could be expected to take violence against animals seriously through misogynist imagery of this kind.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.