By Julia Jagodka

Who doesn’t love puppies? They’re adorable, playful and free-spirited, yet most of these cute pups that people adopt (or buy) are products of a cruel chain of events. According to the ASPCA, female dogs are expected to be ready to mate when they are about 6 months old and are forced to mate for the profit of the owners. Too many loving puppies will be the result of forced and abusive mating. Think about it; this very closely resembles child prostitution in a nonhuman sense.

There are “farms” called puppy mills that are notorious for profiting from “breeding” dogs. These puppy mills are often overcrowded and unsanitary; all unhealthy for puppies confined in small areas and forced to breed. The ASPCA explains that puppies who are bought from puppy mills are more likely to have heart complications, as they are traumatized by the treatment they received at those puppy “farms.”

In addition to heart disease, puppy mill puppies are prone to other congenital and hereditary conditions including blood and respiratory disorders. Puppy mill puppies often arrive in “pet stores” and in their new homes with diseases or infirmities ranging from parasites to pneumonia. Because puppies are removed from their siblings and mothers at a young age, they also often suffer from fear, anxiety and behavioral problems.

The female canines are forced to breed over and over again to fuel society’s demand for purebred puppies, meaning that capitalism is running on the female dogs. Yet this isn’t only happening with dogs, but also with chickens forced to produce eggs, cows forced to produce milk, and pregnant horses forced to produce estrogen; all female bodies are exploited for the profit of our capitalist society.

Moreover, a female dog is actually called a bitch. This is more than a technical term for a female dog; it has larger social meaning. Such language is often used as an insult to demean their status. Its pejorative usage intersects with sexism and heterosexism, because it is also levied as an insult towards a woman or even non-conforming men. A man’s first instinctive response towards a woman who deceives or insults him is to call her a ‘bitch’ (Wrenn 2017). Why do people feel the need to impose these ‘societal norms’ onto dogs and other inhuman animals?

Female dogs are not the only animals who are sexually exploited. Male dogs are also used for “breeding,” of course. It is not uncommon for people to post advertisements of their “studs” online to secure them a mate to produce more purebred pups. Not unlike human men, studs are supposed to be muscular and sexually virile. If these “breeders” can’t get them to naturally reciprocate, then it gets even creepier. There are actual machines, called ‘mating stands’ that enforce this process of breeding if the canines are being uncooperative, or the female is too big for the male (Bailing Out Benji 2017).

There is also something classist and racist about the fetishization of purebreds. Dogs that are not purebred, dubbed ‘mutts’, are often tossed aside, unwanted, and put into shelters. Scruffy mutts, who deserve just as much love as any other dog, are ignored. With this in mind, intersectionality theory is also relevant to canines because of the devaluing of disability. Puppy mills can produce physical deformities and mental disabilities since there is inbreeding occurring. Some dogs are killed instantly after birth because of perceived defects (Fackler 2006). If a dog has a physical disability that reduces their chances of being ‘purchased’ or adopted, they are likely to be put into a shelter or “euthanized.”

Humans are sexualizing and objectifying these animals. Why do humans feel the need to control dogs in such ways? People like the feeling of superiority. People (particularly men) begin to believe they are superior to them, which gives them a justification to exploit them for their profit (Luke 2007, p. 6). Breeding contributes to the homelessness of future puppies. Present day shelters have now been turned into ‘landfills’, with canines often kept in lonely cages, and, for the majority who enter shelters, these dogs will likely be killed. People are treating these canines like puppets and controlling their lives and destinies.

Although humans and dogs are very different biologically, we are more similar than we think. Human females endure sexual objectification at work by male co-workers, or even in restaurants by strangers. Female dogs, meanwhile, are sexually objectified by their “breeders.” This sexual objectification extends to males as well. In “breeding facilities,” males are consistently judged based on masculine gender norms relating to sexual performance. Both male and female dogs are extorted for the “breeders’” profit.

All species should be able to live in unison, and humans should not take advantage of nonhuman animals. The exploitation of canines should be socially rejected. If people continue to protest these puppy mills, hopefully they will go out of business and cease operation. Without puppy mills in play, more potential dog purchasers will resort to adoption. Rather than purchasing dogs like objects, adopting a best friend should be the first action. Puppy mills should be completely disbanded considering that the industry inherently exploits female dogs through forced “breeding” and objectifies these animals by making them commodities.

Works Cited

Fackler, Martin. 2006. “Japan, Home of the Cute and Inbred Dog.” The New York Times, 27 Dec. 2006.

Luke, Brian. 2007. Brutal: Manhood and the Exploitation of Animals. University of Illinois Press.

ASPCA. N.d. Puppy Mills.

Bailing Out Benji. 2017. “The Sexual Perversion Behind Breeding.” Bailing Out Benji, April 20.

Wrenn, Corey. 2017. Module 11: Intersections with Other Animals.

Julia Jagodka is currently a first year student at Monmouth University that is majoring in Biology. After college, she hopes to pursue a career in dentistry. She grew up in Avenel, NJ. Jagodka loves animals, and even helps in nursing feral kittens and finding them new, loving homes. In her free time, she loves to draw and paint. Jagodka is the oldest of her two siblings and that is why she hopes to be a good role model for them while they grow up. Julia speaks fluent Polish, as both of her parents immigrated from Poland about 19 years ago. She had also attended Polish School every Saturday for the last 10 years in order to perfect her Polish. Overall, she is a very enjoyable an engaging person to be around.

Julia Jagodka is currently a first year student at Monmouth University that is majoring in Biology. After college, she hopes to pursue a career in dentistry. She grew up in Avenel, NJ. Jagodka loves animals, and even helps in nursing feral kittens and finding them new, loving homes. In her free time, she loves to draw and paint. Jagodka is the oldest of her two siblings and that is why she hopes to be a good role model for them while they grow up. Julia speaks fluent Polish, as both of her parents immigrated from Poland about 19 years ago. She had also attended Polish School every Saturday for the last 10 years in order to perfect her Polish. Overall, she is a very enjoyable an engaging person to be around.

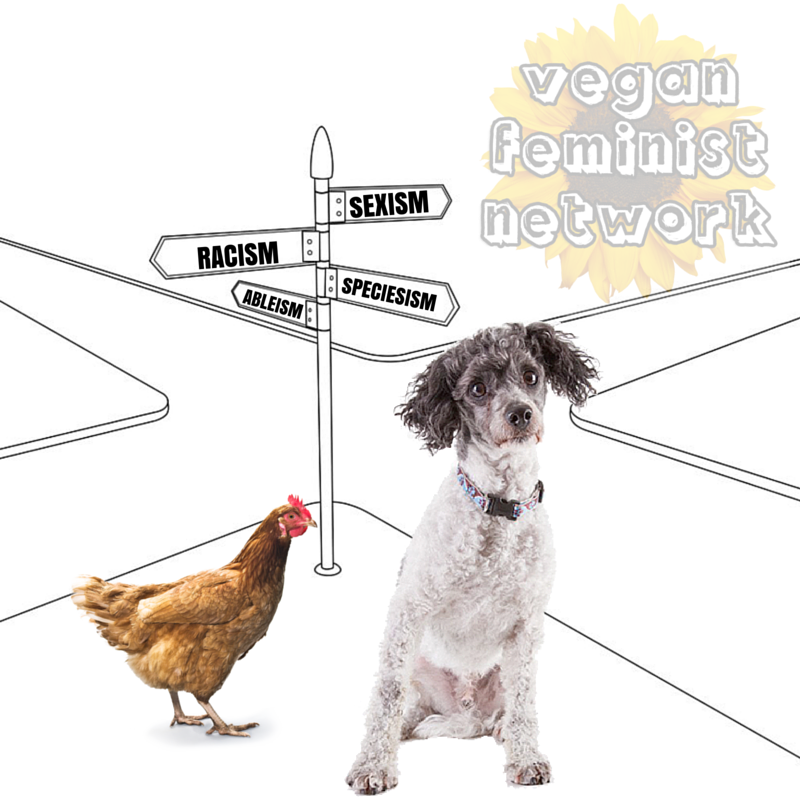

Dr. Wrenn is the founder of Vegan Feminist Network. She is a Lecturer of Sociology and Director of Gender Studies with a New Jersey liberal arts college, council member with the Animals & Society Section of the American Sociological Association, and an advisory board member with the International Network for Social Studies on Vegetarianism and Veganism with the University of Vienna. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory.

Dr. Wrenn is the founder of Vegan Feminist Network. She is a Lecturer of Sociology and Director of Gender Studies with a New Jersey liberal arts college, council member with the Animals & Society Section of the American Sociological Association, and an advisory board member with the International Network for Social Studies on Vegetarianism and Veganism with the University of Vienna. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory.