By Michele Kaplan

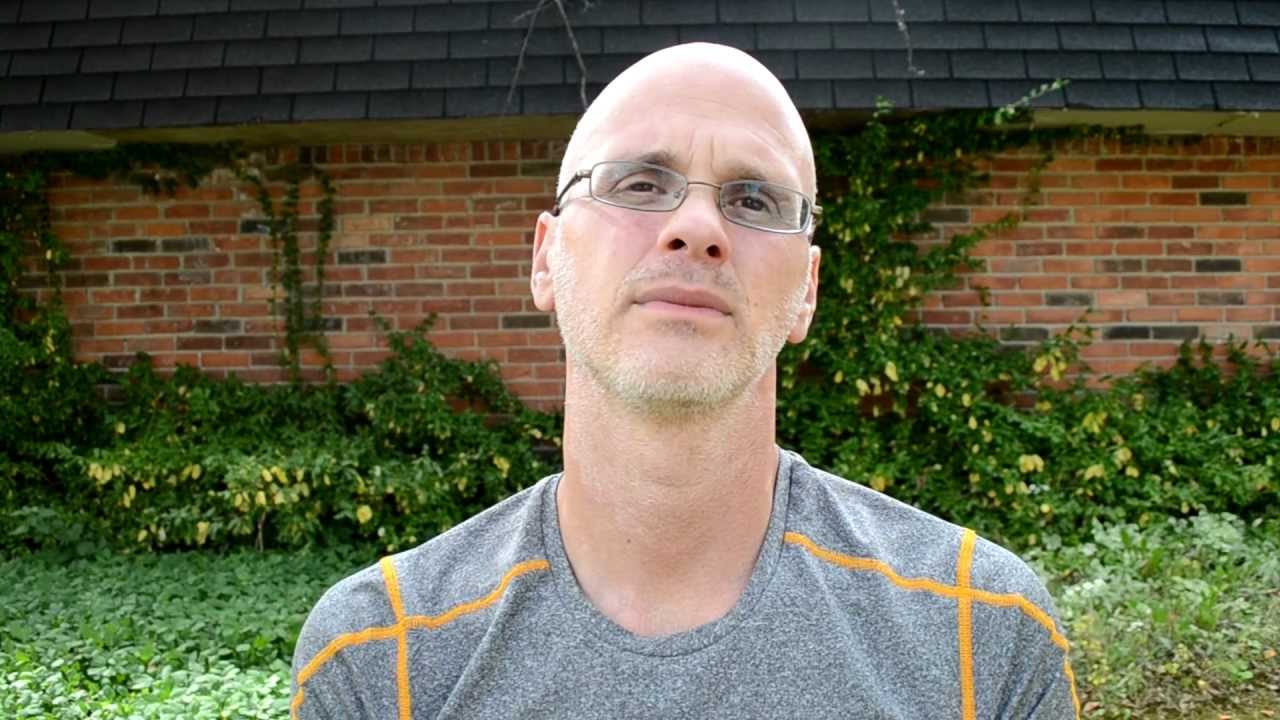

TRIGGER WARNING: The following article is in response to a video posted by Gary Yourofsky. It contains quotes from Yourofsky that reference violence, sexual abuse and rape. The video also contains ableist language and makes the inaccurate claim that every person on death row is guilty. (#FreeLeonardPeltier! #FreeMumia!) Lastly, it contains a great deal of macho posturing, aggressive, graphic and at times disturbing language which may be triggering for many people.

NOT SAFE FOR WORK: Contains foul language.

“After 18 years on trial, the verdict is finally in!” Gary Yourofsky recently declared on social media. “I’ve been found INNOCENT on all charges of supporting rape!”

This being in reference to the backlash from his infamous quote: “Every woman ensconced in fur should endure a rape so vicious that it scars them forever.” The “testimony” (which was in the form of a 28 minute video) goes into great detail as to why he feels he has been treated unfairly.

It should be noted this is not an actual trial. Yourofsky has also declared himself “the judge” (thus his innocence) and ends his testimony by saying “Vegan love to all my supporters who refused to believe these psychotic defamatory lies about me. And finally, to all the organizations and people who have attacked me, claiming that I support rape. I hear by challenge you to top my anti rape position. Go ahead. I dare ya.” He pauses for a moment and then continues in an aggressive posturing “What?! Yeah, I thought so. As usual, I win! Checkmate! You lose!! Fuck you!!”

Yourofsky goes to great lengths in the video to show just how much he despises rapists: “This is what I think should happen to rapists.” He says “Even somebody who rapes a woman in a fur coat (if that ever happens).”

According to Women Organized Against Rape, 1 in 4 human women and 1 in 6 human men will be raped by the age of 18. Considering how much of the norm wearing fur is in our culture, the chances that a fur wearing human being raped, is highly likely.

He continues:

I think his penis and balls should be seared off with a cuticle remover slowly, and then I think two skewers should be shoved into their eye sockets, dragged into another room. And then I think their penis and balls should be dipped into diarrhea and puke. They should be given the option of eating that and then they can save their lives. And if they do eat it, I want to take a gun, put it between their eyes and say ‘I was just kidding’.

In another quote he states that, “Since 1997, thousands of people (mostly vegans) have accused me of condoning rape” and that he has been “continuously harassed with false statements for 18 years.” Okay, so it is clear he does not like rapists. Is he also saying that he never said the infamous rape quote?

“I need all of my supporters to start condemning the liars and deceivers,” he says in the video “who claim that I support rape because I wished it. And I repeat: wished it, upon men and women who actually support rape and murder by draping themselves in fur coats.” He then goes on to say that there isn’t one person on this planet (including a rape victim) who is more against rape than he is.

And while it’s safe to say that someone who has actually survived rape would disagree with that last claim, let’s just move on and focus on what he is actually saying. He does not condone the actual violent act of rape. He merely wishes it upon certain people who he feels are deserving or “evil”

And while I agree that there is a difference between saying “I wish this person gets raped” and actually physically raping someone, I find it odd that he does not understand the consequences of language, let alone the consequence of when a man talks about raping a woman (even if “it’s just talk”). That when he uses rape as a means to punish a person (even if it’s “just talk”), that this still contributes to the collective rape culture, which also impacts the animals such as the dairy cows, who are repeatedly forcibly impregnated (aka raped) in the name of a product. That he doesn’t understand how when an aggressive sounding man starts talking about his rape fantasies, that this can be incredibly triggering to victims of rape. And thus, it is odd that he doesn’t understand how this could possibly create and warrant backlash.

“Wish”

He wishes evil things upon evil and violent people. (And while this includes rapists, domestic abusers and child molesters, none are more violent in his eyes, than the people who partake in the animal agriculture industry.)

“Propose”

“Nobody disagrees with my position on violence, they only disagree who I propose to be violent for.”

“Hope”

“Deep down, I truly hope that oppression, torture and murder return to each uncaring human tenfold!” And lastly he uses the word:

“should”

“Every woman ensconced in fur should endure a rape so vicious that it scars them forever.” As far as rape is concerned, this is what should happen to people (as he also comments on men) who support the fur industry.

This is why people accuse him of supporting rape, and yet he fails to see that.

In his eyes, why are people focusing on his words, when the animals (deemed as food) are being murdered, tortured and in many cases forcibly impregnated (aka: rape) on a daily basis? This would not occur if there weren’t people who were financially supporting the industry. This should be the focus, not something he says.

And in this regard, he is right. There is a deep social conditioning in our society that has raised us to believe that violence against certain animals are okay. That says certain animals are here to be our food and clothing and have no other purpose. The animal agriculture industry goes to great lengths to encourage this disconnect, by hiding the truth of the factory farms and putting the image of the jolly animal on their package, to give off the impression that the animal is happy to be your food.

And when we see the packages of meat, the appearance is so far removed from what the actual animal looks like, that it becomes very easy to ignore and even forget the origin. The animal agriculture industry is so freaked out about their customers learning the truth of their industry, that they have gone to great lengths to lobby the government so it becomes illegal to expose the cruelty. Furthermore, how else will you ever get your protein and calcium? We are raised to believe that we can not be strong and healthy, if we do not consume animals, which is yet another myth perpetuated by the animal agriculture industry.

And when we see the packages of meat, the appearance is so far removed from what the actual animal looks like, that it becomes very easy to ignore and even forget the origin. The animal agriculture industry is so freaked out about their customers learning the truth of their industry, that they have gone to great lengths to lobby the government so it becomes illegal to expose the cruelty. Furthermore, how else will you ever get your protein and calcium? We are raised to believe that we can not be strong and healthy, if we do not consume animals, which is yet another myth perpetuated by the animal agriculture industry.

And I will also agree that there is a huge disconnect regarding the issue of rape and speciesism and that many anti-rape advocates and feminists do not know (or do not make the connection) between the dairy cow and the collective rape culture. They don’t know (or are taught not to care) that the only way a cow will continuously produce milk, is if she is repeatedly impregnated against her will (aka: rape), only to have her babies stolen from her time and again. Because to the industry, her baby is nothing but veal. This happens over and over until the mother cow is so emotionally and physically run down, that she is unable to produce babies (and thus milk), and then she is slaughtered. But we are taught to not worry about that because we are told that cows (and other farm animals) are unfeeling, unloving, creatures who do not respond to their environment, which is yet another myth perpetuated by the industry.

When he makes those particular points, he is correct. However, he remains confused as to why people are so distracted by his statements and they don’t just focus on what is a far worse situation. The truth is just because something is worse, doesn’t negate the consequences. I could say, “Oh, I hope you get shot and die a miserable slow painful death”. Meanwhile genocide is occurring in another part of the world. Yes, the latter is worse, but that truth does not remove the fact that there are still consequences to what I said.

Granted, Yourofsky will sometimes clarify his message and say that he only wishes violence upon people who indirectly or directly partake in the animal agriculture industry, because he feels that maybe if humans experienced the level of violence that the animals experience, then they would cease to contribute to the violence. However, he only clarifies some of the time. And when he does, people have to first get past his initial statements of wishing, hoping, and proposing violence against them to get to that point. Other times he just goes off on a graphic rant about what he thinks should happen to people who are evil.

The truth is, verbally advocating for the violence against a person who isn’t vegan only works against the cause of liberating the animals. Furthermore, it is hypocritical since unless you were born vegan, you too were once contributing to the violence. I know I was. And even now as vegans, when the grains, fruit and veggies are harvested, insects and field mice are often killed in the process. When the homes that we live in are constructed, harm is also done to the animals who were already living on that land. Many vegans require medications that were tested on animals. And yes, let’s work to change the system that makes it nearly impossible to not harm animals, but the present truth is that not one person is completely innocent of this.

Lastly, as activists we must remember that there is a difference between what feels good and cathartic to express, and what makes for an effective tactic and argument. The difference between what is best to share in a diary or in a private conversation, and what we share to the rest of the world, especially to people who we’d like to join us. Because, yes the animals need as many people on their side as possible, so that the goal of animal liberation can be achieved.

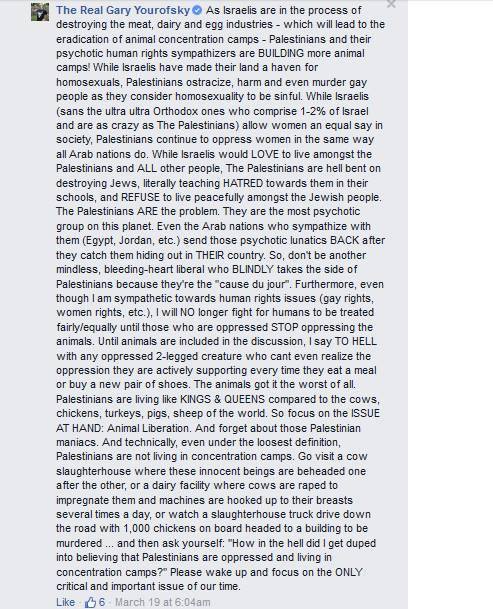

Gary Yourofsky has since put out another video entitled “Palestinians, Blacks and Other Hypocrites” where he addresses the issue of people in the community “unfairly” accusing him of making racist statements. Hmm, I wonder why.

This essay originally appeared on Rebelwheels’ Soapbox on May 17, 2015.

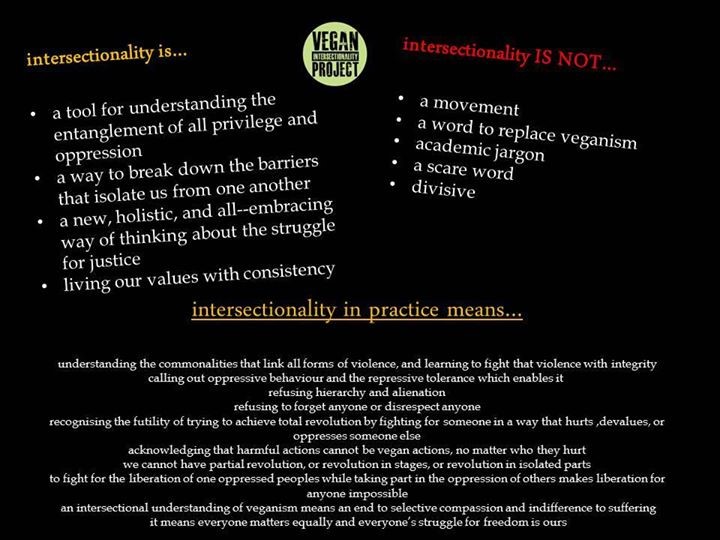

Michele Kaplan is a queer (read: bisexual), geek-proud, intersectional activist on wheels (read: motorized wheelchair), who tries to strike a balance between activism, creativity and self care, while trying to change the world.

Michele Kaplan is a queer (read: bisexual), geek-proud, intersectional activist on wheels (read: motorized wheelchair), who tries to strike a balance between activism, creativity and self care, while trying to change the world.