Trigger Warning: Discusses sexual abuse, domestic violence, heterosexism, eating disorders, and suicide.

| Before I dive into this article I have to confess that writing it was not an easy decision. I’ve been wanting to write about it for a very long time but undressing myself before the eyes of people I’ve never seen, talked to or interacted with in any way can open the door to a lot of hatred. But it also opens the doors to all of you out there, who can relate to my experiences, and my hope is that you too, can turn violence into activism. This story is for you, brothers and sisters. |

I too have regarded women as prizes. I am no heroine. And for that I am sorry.

I too have regarded women as prizes. I am no heroine. And for that I am sorry.

I was born and raised in Brazil, a tropical paradise, people say, where everyone is always partying, LGBTQ flags flapping on a hot breezy day, gunshots and pools of blood, a country which has as many steak houses as the U.S has Starbucks’ stores.

Growing up there was far from paradise. I discovered glimpses of my sexuality at a very early age, so young I’m not sure how old exactly I was but I’m going to estimate 5 years old. I remember this girl came to play with me and I took her to my bedroom. I loved to pretend I was camping so I used to make tents with my bed sheets. I invited her in. I kissed her. We touched each other.

About a year later, age 6 a man came to live with us. I’ve always had a talent to read people and I knew something about him was terrifying. I refused to call him father not because I was jealous that my mother was with someone but because I could smell the violence in him. I called him “Big Bee” (if you translate it from Portuguese), probably because I had been stung by bees before and I knew it hurt a lot.

Like most predators, he took some time to unveil his true self. Before that he had to gain our trust and approval, which he tried to get from me by buying me things, taking me to places I wanted to go, and by supposedly making my mother happy. I pretended to give him my trust but inside I was shaking.

Then the days when he would come home somewhat drunk started. At first it was because he had a bad day at work, long hours of art direction call for some whiskey. Those days started to get more frequent, the tone of his voice started to raise, his hands also started to raise. I put myself between him and my mother day and night, I begged him to stop, leave her alone. For some reason I knew I was immune to him. I didn’t fear for my life, I feared for my mother’s.

Every night I knew he was coming home because I could hear the revving sound of his car entering the garage. Sometimes I would hear it for minutes because he was too drunk to drive through it. I would never fall asleep before knowing he had arrived, even when it was very late and I secretly hoped he would die alone in a car crash. But he never did. He always came back.

He would come straight to my bedroom since my mom had started sleeping with me. Sometimes she would come out to talk to him. Inevitably I had to go out to stop him from beating her because he always did.

I studied a lot then, from 8am to 4pm. I loved school and I hated home. I never told anyone about what was happening at home. I became so hollow and cold I remember this one time I was looking at myself in the mirror, forcing myself to cry right before I went to school to see if one of my friends would notice so I could tell them what was going on. Not one single drop came out. I grinned and beared. It was almost relieving, to live this double life. In the eyes of the world I was just this kid, innocent and naive.

The drinking then started to happen at home. He would sit in his study, writing his pathetic poetry, pretending to be some kind of artist while quenching his thirst with a Johnny Walker bottle. He would fall asleep with his mouth open, in such deep sleep I imagined myself throwing all sort of disgusting things in it.

I have almost completely erased the 6 years of abuse from my mind without erasing the consequences of it, of course. But I vividly remember one night when I must have fallen asleep and I woke up to sounds heavy suffocation. I jumped out of bed. He was giving my mother a choke hold. My mother, someone who suffered from asthma, a choke hold. I jumped on him, I took him off her. I think this was also the same night when he had almost broken her wrist.

In anticipation of people saying I became gay because of an abusive male figure in my life, even though it’s a fact I was already attracted to girls before, I started to give boys more of my interest but let me point out, I was obsessed with Leonardo DiCaprio – androgyny anyone? I was reassured not all boys were abusive and violent but I knew I didn’t want to be with them.

In anticipation of people saying I became gay because of an abusive male figure in my life, even though it’s a fact I was already attracted to girls before, I started to give boys more of my interest but let me point out, I was obsessed with Leonardo DiCaprio – androgyny anyone? I was reassured not all boys were abusive and violent but I knew I didn’t want to be with them.

Not long then my mother had a brain aneurysm, right in front of me. She told me she covered her face because she felt like her eye was coming out. She was identified with aneurysm pretty quickly. I told her it was going to be okay, but that she was going to look like Sigourney Weaver in the movie Alien – basically saying that she was going to have her head shaved, operated.

She survived. With no neurological damage. A true miracle if you ask me. It would all have been good if we hadn’t gone back home and it had taken another act of violence from him to finally dictate that we were leaving for good. I was in my pajamas.

Not surprisingly my sense of justice and determination to fight against injustices only grew bigger: the same way I felt it was my responsibility to protect my mother, I felt like it was my responsibility to also help others. “Trauma and activism appear to be in contradistinction—the former defined by exclusivity and concealment, being hidden and out-of-sight; and the latter by action, out-in-the-open, in public,” says Outspoken.

I had always been drawn to helping animals, cats and dogs for the most part, but insects, birds and fishes also. At age 15 I also thought I was helping women by getting involved in relationships in which women seemed to need my help with a specific issue: straight rebel girls who wanted to piss off their parents, girls who couldn’t feel anything at all, girls who were taking a break from their current relationship, later in life married women, women who were just as lost as me. I would immerse myself completely in them, ensuring that they were completely in love with me. It was almost like art for me, how they would put me up on a pedestal.

The cycle basically went down like this: get involved into a relationship with a woman who supposedly needed an issue resolved, be the heroine of the day, get bored because the “challenge” was finished, leave. A few things to point it out is that this cycle was very gradual. It was never about the sex, quite the opposite, I despised one night-stands. It was for me a narcissistic need for attention, to feel loved but to anticipate the inevitable destruction of that relationship and so be the one who leaves it first.

I would then start to destruct the relationship, usually by cheating. I have cheated on almost every single girlfriend I had and I had many – I will not get into detail of every individual since I don’t have the consent to share our story publicly. I had given them what I thought they wanted and it was time for them to be on their own. So I abandoned them. “If I could recover from all the atrocities I had gone through, they sure could recover from a breakup,” I told myself over and over again to justify my behaviour.

Those relationships made me feel alive, made me feel like I was in charge. Between my self-destruction spiral with anorexia, a disease in which one disappears to be seen, bulimia nervosa (and very shortly with alcohol), my attempt of suicide, and my struggle with homophobia (Brazil has highest LGBTQ rate of murder in the world), from verbal to physical abuse, those relationships were something I had control of and I didn’t even have to feel guilty about it: it was consensual.

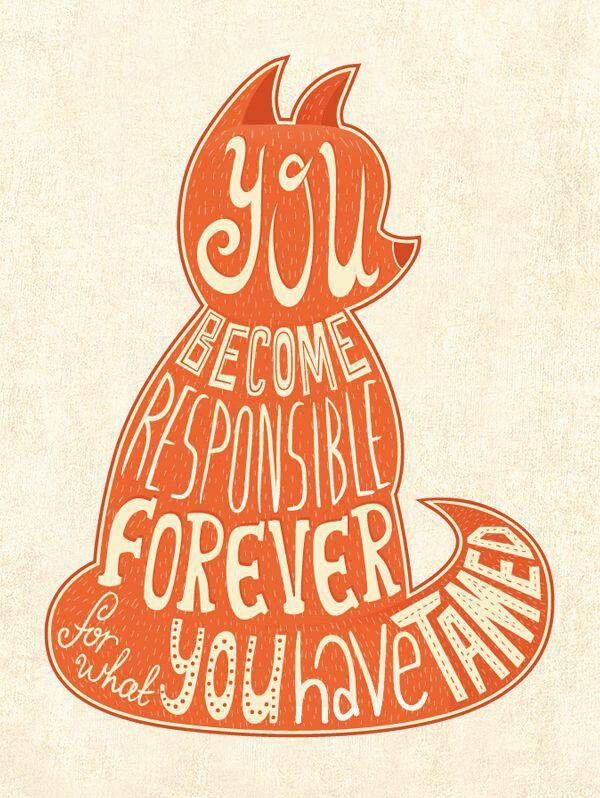

My favorite character in The Little Prince was the Fox, “People have forgotten this truth,” the fox said. “But you mustn’t forget it. You become responsible forever for what you’ve tamed. You’re responsible for your rose.” My mother, seeing my vicious patterns tried to warn about the consequences. But I did not want to take love advices from her. Not after everything she had put me through.

I left Brazil to come to the US in hopes to leave my demons behind. But they followed me. I became involved in LGBTQ activism, feeding the homeless and became involved again into helping cats and dogs. My good deeds were still taking place while I continued to treat women like trophies, to self-destruct and of course, I continued to eat the flesh and drink the secretions of non-human animals.

It was time to go back to therapy. I was 26 and I was still getting involved in relationships in which I was the heroine, bragging to my friends about my “adventures.”

In parallel I became the board director at a dog and cat rescue. It was then that I came to realize the hypocrisy into saving some animals but not all by watching slaughterhouse videos, today I recommend this one. Long story short, I went vegan overnight, and most importantly I became a vegan activist.

I knew I needed help. To understand why self-destruction was taking over my life and how I could end my relationship patterns. It was because of doctor Laura and over 1 year of intense therapy (this was followed by other years of therapy I had done) that I was able to identify my mechanisms and make sure my patterns were broken. It was not easy. It was painful, humiliating in many ways, but enlightening.

I am a product of a broken home, like Placebo would say. It is true that childhood trauma affects and changes someone forever:

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study is something that everybody needs to know about. It was done by Dr. Vince Felitti at Kaiser and Dr. Bob Anda at the CDC, and together, they asked 17,500 adults about their history of exposure to what they called “adverse childhood experiences,” or ACEs. Those include physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; physical or emotional neglect; parental mental illness, substance dependence, incarceration; parental separation or divorce; or domestic violence. For every yes, you would get a point on your ACE score. And then what they did was they correlated these ACE scores against health outcomes.

What they found was striking. Two things: Number one, ACEs are incredibly common. Sixty-seven percent of the population had at least one ACE, and 12.6 percent, one in eight, had four or more ACEs. The second thing that they found was that there was a dose-response relationship between ACEs and health outcomes: the higher your ACE score, the worse your health outcomes. For a person with an ACE score of four or more, their relative risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was two and a half times that of someone with an ACE score of zero. For hepatitis, it was also two and a half times. For depression, it was four and a half times. For suicidality, it was twelve times. A person with an ACE score of seven or more had triple the lifetime risk of lung cancer and three and a half times the risk of ischemic heart disease, the number one killer in the United States of America. (Nadine Burke Harris 2014)

Do my destructive relationships have do with my past? Absolutely. But it does not excuse me or anyone else from seeking help. Multiple times if you have to. Our past cannot be used as an excuse to justify our actions.

I overcame my personal trauma and transformed it into a catalyst for activism. It was most likely because of my trauma that fighting against injustices was so dear to me. However, as you have seen, I am no heroine. Despite my exhaustive dedication to Animal Rights and for that matter, to all forms of oppression, I have treated women like trophies. I have never been a predator, or engaged in any form of nonconsensual act but I have used those relationships as a way to feel empowered and then to self-destruct. I have also never shared anything about the women I was with publicly without their consent but I have disregarded the feelings of countless individuals.

What triggered me to write this article was the return to Facebook of Hugo Dominguez, former Direct Action Everywhere organizer, who has admitted to sex crimes. I see a few parallels between us, this is why I want to bring him into this story.

Hugo may have acknowledged his behaviour but he hasn’t actively and truly sought help. Someone who wants to get better will remove themselves from situations that will trigger the behavior again, and in his case his attention-seeking addiction is being fed by his latest return to Facebook.

I too have regarded women as prizes, so I know exactly where Hugo stands. I too have moved away from my country trying to escape my past, I too have taken a few months to reflect but those were band-aids on a hemorrhage. Overcoming a vicious behaviour takes time and commitment. It also includes giving time and space to the victims.

I have described my upbringing in detail to inspire others who have gone through childhood trauma to seek help. Consciously or unconsciously I have let my past dictate my present but we must use traumatic experiences to push us forward, to help us and others grow. I sincerely hope Hugo can.

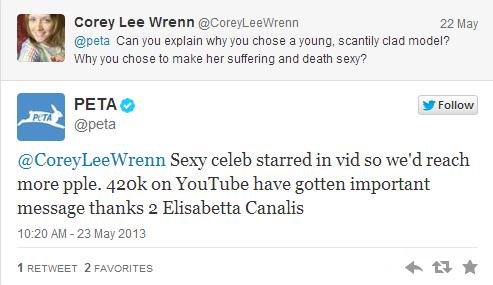

We have seen the dangers of hero worship, so please, let’s destroy pedestals and let’s embrace one another on the same level.

Co-founder of Collectively Free, Raffaella Ciavatta is vegan animal liberation activist, art director, poet, photographer wanna-be, DJ in some past live and most importantly… a big dreamer who makes things happen.