By Dr. C. Michele Martindill

“Ageism? Who cares about old people anyway? I volunteer with a group of white women over the age of 50. They are so behind the times and not helpful at all,” said a vegan.

“Why was it important for you to mention their age or gender?”

“Um…I don’t know.”

Vegans seem to at least recognize the words racism, sexism, classism, ableism and speciesism, but ageism is consistently left off that list of oppressions. Erasure. Silencing. Stereotyping older people as useless, past their prime, set in their ways and not able to contribute to the vegan movement. As one vegan once posted on Facebook, “Taking a stand against ageism feels too much like a single issue campaign, not really worth the effort. People need to just go vegan.” Really? Ageism is just a single issue campaign?

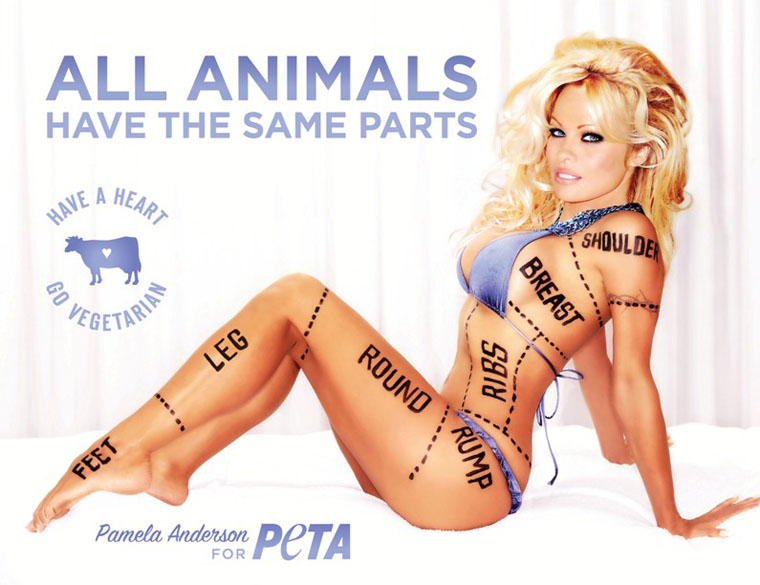

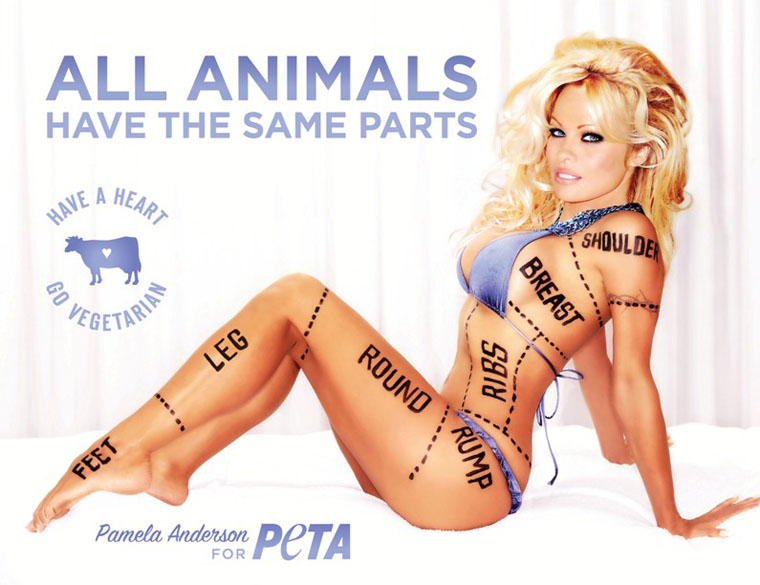

PeTA is well known for its sexist advertising campaigns involving young women who pose partially or completely nude in an effort to get the public to stop eating or otherwise harming animals, e.g. celebrity Pamela Anderson posed in an almost non-existent bikini with her body marked off in the same way a butcher marks off the body parts of a cow—just to make the point that “All Animals Have the Same Parts.” Few would be surprised to learn that particular ad was banned in Montreal, Canada over the blatant sexism (Cavanagh, 2010), but how many people are aware that PeTA sponsors a Sexiest Vegan Over 50 contest? Judging is based on the entrant’s enthusiasm for their vegan lifestyle and “PeTA’s assessment of your physical attractiveness (PeTA, 2014).” Through a contest that objectifies women aged 50 and older, the public learns that a vegan lifestyle and diet should lead to what really matters in life—physical attractiveness. As if women don’t face enough pressure when they’re young to conform to standards of beauty created and institutionalized by men, they now have to face those same sexist standards as they age.

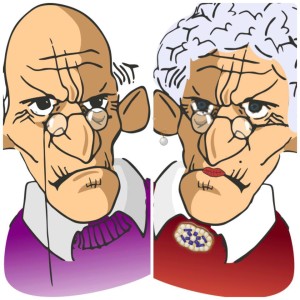

Of course, there are other stereotypes of older women in the animal rights movement. The Grumpy Old Vegans (GOV) Facebook page continues to use an avatar or logo depicting an older man and older woman with pronounced wrinkles, unfashionable clothing, grey hair, sour expressions and the woman is wearing pearl jewelry, a most un-vegan adornment (Grumpy Old Vegans, 2015). The representation of this pair as perpetually grumpy serves to stereotype older people, women in particular, as crotchety and is a form of ageism. While there is little doubt that if the GOV Facebook page used a logo featuring a couple in blackface or Native Americans as r-skins there would be a great public outcry, to date few have spoken up against the ageism of the wrinkle-bound couple logo.

Considering that vegans claim veganism is against all oppression, it is distressing to see them rank order which oppressions matter the most and which ones don’t even make the list, namely ageism. At the very least a definition of ageism is needed, explaining why and how it affects women more than men. Ageist stereotypes of older women affect the way they are stigmatized and contribute to their erasure from public concern. It is also important to explore how it is that men in leadership roles of the vegan animal rights movement can be so dismissive of older voices, particularly the voices of women.

AGEISM: The definition of ageism is straightforward–it is discrimination and prejudice against people based on their age, and is directed toward the very young as well as those who are considered old or elderly. Ageism is structural or systemic in our social world, meaning people learn it and enact it through social institutions, language, and organizations. People often don’t notice when they’re socially reproducing ageism, e.g. it is commonplace when someone forgets where they put something to say they’re having a senior moment, as if aging is universally defined by memory loss. Ageism is a relationship of power in that the dominant group in society uses ageism to oppress, exploit and silence those who are very young or much older. Just as the vegan animal rights movement stands against racism, sexism, ableism, classism, and speciesism, it stands against ageism—or at least some movement members claim it does. That remains to be seen.

STEREOTYPING: The tools of ageism are stereotyping and attaching stigmas to older people. Stereotypes are overly simple, fixed, rigid or exaggerated beliefs about an entire group or population of people. Stereotypes can lead to and be used to justify prejudice and discrimination. Aging women experience stereotyping more than men. Their bodies are criticized based on wrinkles, weight, hair color, posture, incontinence and overall loss of beauty; men may be similarly criticized, but are most likely regarded as distinguished in their later years and have the social capital—kinship, friendships, co-workers—to slough off negative stereotypes. Some of the most often used stereotypes of older people include:

1) All old people get sick and have disabilities, including hearing loss, urinary incontinence and blindness.

2) Old people are incapable of learning anything new; they are set in their ways.

3) Old women are a burden on everyone.

4) “Old people are grouchy and cantankerous.” (The Senior Citizen Times, 2011)

These and other stereotypes are communicated in multiple ways throughout the vegan animal rights movement. In a recent Facebook discussion of how PeTA uses young blonde white women in their advertising campaigns several women pointed out the sexism and racism of such a tactic. None mentioned ageism. One man stepped in to ‘mansplain’ and defend PeTA:

Humans are sexual beings and there’s nothing wrong with that. This doesn’t degrade women the same way half-naked male models don’t degrade men. It just looks like you’re actively looking for sexism, racism, or some sort of discrimination in an effort to be politically correct. I don’t think that’s a good approach. (Toronto Vegetarian Association, 2015)

When told by a woman that it degrades women to be reduced to the sum of their body parts and that they are only heard if they are considered sexy, this same man responded:

How exactly does it suggest that being sexy is the only way people will hear you if you’re a woman? That’s just ridiculous. People listen to not attractive people. Look at Hilary Clinton for godsake. [Emphasis added] That’s just a weird argument with no validity. I’ve never seen someone turn down a conversation with a woman based on their attractiveness.

How exactly does looking at and LIKING someone’s body disrespecting them? It seems like YOU are the one degrading women here. And it’s funny – aren’t feminists about women having freedom to wear what they want without being judged? Double standard much?

Oh my. If it’s not degrading to use half-naked men in advertising, then it’s okay to use half-naked women? What this man does not understand is how men have the power to deflect attempts at objectification. Women do not, not at any age. Please note there’s no mention of ageism in his reasoning, but Hilary Clinton, current presidential candidate in the United States, is held up as an example of “not attractive people” who can still get attention. Furthermore, this man calls out the women in the conversation for being bad feminists since they failed to support his admiration for attractive young women. The explicit ageism in this conversation was never mentioned, and it served to socially reproduce acceptance of ageism, acceptance of making disparaging remarks about women based on their age and appearance.

STIGMA: Stereotypes lead to stigmas. Sociologist Erving Goffman (1922-1982) defined stigma as society attaching an undesirable attribute to an individual and then reacting negatively to that individual in such a way as to rob them of their identity, their ability to function or fully participate in society (Link & Phelan). In our social world, age is seen as an undesirable physical attribute, a stigma that is attached to women through man dominated ideologies which favor younger women for their sexualized bodies. Whenever a person or group displays a stereotypical representation of women as wrinkled, grouchy, or set in their ways, they contribute to the stigma of aging and socially reproduce ageism.

Criticism of a stereotypical ageist logo on the GOV Facebook page was met with dismissiveness on the grounds that people have a right to identify themselves as old and grumpy, and then the author, who was a man, made an ad hominem attack on the person who challenged his group:

…if you truly believe that people who identify themselves as old, grumpy and vegan and run a page with that title, using caricatures to represent themselves, are ageist for those reasons alone then your thinking is as muddled as that of those who made the allegation originally.

The man continued to defend his group’s ageist logo by dismissing sociological research and by stating that since the majority of the group “liked” it on Facebook, the logo could not possibly be ageist:

sociology is not an exact science. For that reason, it would be foolish to regard every utterance from sociologists as gospel. The rebuttal of this allegation issued on the page was ‘liked’ by a large number of people, many of whom expressed appreciation for a page they identified with, as they often felt invisible in a movement that celebrates youth. There were no adverse comments. In short, there is no substantive evidence to support the allegation.

What some vegans fail to see is how their actions affect others outside of the group. A logo or mascot is not ageist based on the vote of a membership who benefit from the stereotyping; ageism is grounded in any action that stigmatizes people based on their age.

Kyriarchal or Interactive Systems of Oppression: Kyriarchal social justice addresses all forms of oppression—racism, sexism, ageism, classism, ableism, and speciesism—and focuses on the dynamics of how these systems are interactive, crisscrossing and layered oppressions in the lives of individuals and groups (see below for a definition of kyriarchy—what was formerly referred to as intersectional). All oppressions are socially reproduced and linked by social institutions, through the economic, medical, legal, educational, religious and any other type of social institutions people navigate on a daily basis.

Too often when women in the vegan animal rights movement point out institutional ageism they are told by movement leaders that drawing attention to oppressions such as ageism is wrong, that kyriarchal social justice means we should just get along and go vegan for the animals because ending speciesism is all that matters. These vegans seem fine with claiming they care about humans and readily assert they are opposed in a general sense to things like racism, but they rank order oppressions and try to cherry pick the oppressions that matter most to them, leaving the rest to sit unnoticed. Why? In part they fear doing harm to the vegan animal rights movement and its organizations; they fear attention will be drawn away from ending speciesism or that outsiders will not join the movement if they have to stand against all oppressions. It is also difficult for the movement to envision how to address kyriarchal social justice when most of the leaders are men and eighty percent of the followers are women, when most of the membership is white, cis-gendered, young, without disabilities and not living in poverty. By not addressing ageism vegans socially reproduce and reify the stereotypes and stigmas associated with aging in our society.

AGEISM DOES REAL HARM: What harm is there in ignoring ageism? Plenty. In a recent study, researchers at the University of Southern California found that negative stereotypes about aging can potentially impair the memory of older people. “The study found that a group of older people asked to perform memory tests after reading fictitious articles about age-related memory problems did less well than a group given articles on preservation of and improvement in memory with age (Shuttleworth, 2013).” The older people who experienced memory loss fell victim to a self-fulfilling prophecy and the cliché of older people losing cognitive function just because they are old.

In addition, stereotypes keep people from seeing the realities of aging; they erase and marginalize older voices. Telling older people—especially women—to just go vegan will not address the financial problems faced by an aging population. Older women are at particular risk to be living in poverty. A report from 2012 based on US Census Bureau data reveals that over half of elder-only households lack the financial resources to pay for basic needs. Sixty percent of women aged 65 and older who live alone or with a marriage partner cannot meet day-to-day expenses. Women of retirement age are hit particularly hard by economic insecurity. Their pensions are smaller than those of men, they own fewer assets, and lack the education and job skills needed for post-retirement employment. Some of this economic disparity is the result of women leaving their careers to care for families and for their own elderly parents, and thereby losing opportunities for promotions as well as building up Social Security income. Also, women outlive men, leaving them alone with a single income and having to exhaust assets just to have shelter and food (Wider Opportunites for Women, 2012).

Older women of color are more likely than white women to have sufficient retirement incomes. Almost 50% of white women have insufficient retirement incomes to afford daily needs, while nearly 75% of Black women, 61% of Asian women and 75% of “Hispanic” (see US Census Bureau definition of Hispanic below) women were in households that could not afford basic expenses—even with Social Security income and Medicare coverage (Wider Opportunities for Women, 2012). Vegans who stereotype and stigmatize older women as self-sufficient and out of touch with animal rights might want to consider how these women have more pressing concerns in their lives, e.g. how they will make the next rent payment or pay the heating bill. Keep in mind, too, these numbers do not take into account those who are homeless or who live in elder care of some sort.

STOP AGEISM in the VEGAN MOVEMENT: All vegans can work to eliminate ageism and extend empathic understanding to older people by considering how clichés and gaslighting—silencing someone with a barrage of questions and attacks—frame interactions with older people. Following are ten of the most often repeated ageist clichés found throughout the vegan animal rights movement and in vegan Facebook discussion threads:

1. “I feel old, so I know what you’re feeling even though I’m not really old myself.”

No, you don’t know what it means to feel old. You haven’t experienced it. Just as a white person has no way of knowing what it feels like to be Black, young people come across as dismissive and patronizing when they pretend to know how it feels like to be old.

2. “Age is just a number” or “You’re only as old as you feel.”

Condescending! Implicit in these statements is the view that young is better than old, so just don’t look at the number.

3. “I’m having a senior moment.”

This cliché is most often uttered when someone wants to explain a mental lapse of some kind or a moment of forgetfulness, and it stereotypes “seniors” as having diminished mental capacities. It’s not only ageist, but ableist!

4. “Ageism feels like a single issue campaign (SIC). Let’s keep the focus on the animals.”

Veganism is an effort to end the exploitation of all animals, including humans. Ageism in its many forms is exploitation. It misrepresents veganism to deny ageism exists or that its effects are harmless.

5. “I’m not ageist! You’re the one being ageist by bringing it up!!”

Here’s an example of reverse ageism. There is no such thing as reverse ageism, just as there is no such thing reverse racism. Only the group holding power can inflict oppression.

6. “I’m old, so I can say what I want about old people.”

Yes, old people can discuss aging in ways young people can’t, but remember disparaging remarks and stereotypes hurt ALL old people. Think about the big picture!!

7. “Jokes about aging are culturally relative. We poke fun at old people in the United Kingdom.” OR “Lighten up! Get over yourself!”

If a vegan anywhere in the world knows their words or actions will hurt others by contributing to ageism or any other oppression, then they can’t use cultural relativism as an excuse for their disrespectful behavior. It’s that simple.

8. “Old people discriminate against young people, so why can’t we make fun of old people?”

Yes, some older persons may be prejudiced against young people or discriminate against them, but stereotypes don’t stick to young people, don’t leave young people marginalized because of their age.

9. “You look like my grandma.”

While most likely meant as a compliment, these words stereotype women as being primarily in nurturing roles, especially later in their lives.

10. “The older generation let us down on social justice issues, so why should we care about them?”

Stop blaming the victims!!

In a cis-gendered white man dominated society ageism is used to silence older women. It’s a continuation of the objectification that starts early in the life of every woman. Older women are regarded as the sum of their body parts, parts that are stereotypically seen as wrinkled, sagging, graying and useless. Men dismiss the educational achievements and work of older women as a means of devaluing the contributions they make. The vegan animal rights movement has yet to acknowledge ageism or speak out against it. Instead, the older women who are in the movement support its man dominated leadership, both denying ageism exists and acting as apologists for the leadership. They tell those who mention ageism to not take themselves so seriously. Ageism is not a joke to be laughed off and forgotten. Vegans seem to at least recognize the words racism, sexism, classism, ableism and speciesism, but ageism is consistently left off that list of oppressions. At best, it is seen as a single issue campaign within the vegan movement, an object for disdain that distracts from the mission of saving other animals. Mark these words: The vegan social movement will not survive as long as it practices oppression against one group in order to elevate the needs of another group.

In a cis-gendered white man dominated society ageism is used to silence older women. It’s a continuation of the objectification that starts early in the life of every woman. Older women are regarded as the sum of their body parts, parts that are stereotypically seen as wrinkled, sagging, graying and useless. Men dismiss the educational achievements and work of older women as a means of devaluing the contributions they make. The vegan animal rights movement has yet to acknowledge ageism or speak out against it. Instead, the older women who are in the movement support its man dominated leadership, both denying ageism exists and acting as apologists for the leadership. They tell those who mention ageism to not take themselves so seriously. Ageism is not a joke to be laughed off and forgotten. Vegans seem to at least recognize the words racism, sexism, classism, ableism and speciesism, but ageism is consistently left off that list of oppressions. At best, it is seen as a single issue campaign within the vegan movement, an object for disdain that distracts from the mission of saving other animals. Mark these words: The vegan social movement will not survive as long as it practices oppression against one group in order to elevate the needs of another group.

Notes

1 Kyriarchy is used in this essay to refer to networks or systems of interactive oppressions. The word emerged from the work of Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza. It is taken from the Greek kyrios, meaning lord or master, and archo, meaning to govern. It is considered a more inclusive and expansive term than patriarchy.

2 The use of “Hispanic” in this reference is based on the US Census Bureau definition: “People who identify with the terms “Hispanic” or “Latino” are those who classify themselves in one of the specific Hispanic or Latino categories listed on the decennial census questionnaire and various Census Bureau survey questionnaires – “Mexican, Mexican Am., Chicano” or ”Puerto Rican” or “Cuban” – as well as those who indicate that they are “another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.” Origin can be viewed as the heritage, nationality group, lineage, or country of birth of the person or the person’s ancestors before their arrival in the United States. People who identify their origin as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish may be of any race.” While it is not an optimal definition, it was all that was available for this data set. Much work needs to be done in defining and mapping the use of such categories. http://www.census.gov/population/hispanic/

References

Cavanagh, K. (2010, July 15). Pamela Anderson’s sexy body-baring PETA ad gets banned in Canada. Retrieved from NY Daily News: http://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/gossip/pamela-anderson-sexy-body-baring-peta-ad-banned-canada-article-1.463753

Grumpy Old Vegans. (2015, May 12). Grumpy Old Vegans. Retrieved from Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GrumpyOldVegan?fref=ts

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (n.d.). On Stigma and its Public Health Implications. Retrieved from http://www.stigmaconference.nih.gov/LinkPaper.htm

PeTA. (2014). PeTA’s 2014 Sexiest Vegan Over 50 Contest. Retrieved from PeTA Prime: http://prime.peta.org/sexiest-vegan-over-50-contest/details

Shuttleworth, A. (2013, July 8). Are negative stereotypes about older people bad for their health? Retrieved from NursingTimes.net: http://www.nursingtimes.net/opinion/practice-team-blog/are-negative-stereotypes-about-older-people-bad-for-their-health/5060639.blog

The Senior Citizen Times. (2011, November 23). Top 20 stereotypes of older people. Retrieved from The Senior Citizen Times: http://the-senior-citizen-times.com/2011/11/23/top-20-stereotypes-of-older-people/

Toronto Vegetarian Association. (2015, April). Toronto Vegetarian Association. Retrieved from Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/torontoveg/permalink/10152808399662686/

Wider Opportunities for Women. (2012). Doing Without: Economic Insecurity and Older Americans. http://www.wowonline.org/documents/OlderAmericansGenderbriefFINAL.pdf.

Wider Opportunities for Women. (2012). Doing Without: Economic Insecurity and Older Americans. http://www.wowonline.org/documents/OlderAmericansGenderbriefFINAL.pdf.

Dr. Martindill earned her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Missouri and taught there in the Sociology Department, the Peace Studies Program and the Women’s and Gender Studies Department. Her areas of emphasis include political sociology, organizations and work, and social inequalities. Dr. Martindill’s dissertation focuses on the no-kill shelter social movement and is based on ethnographic research conducted during several years of working in an animal shelter. She is vegan, a feminist and is currently interested in the stories women tell through their needlework, including crochet, counted cross stitch and quilting. It is important to note that Dr. Martindill consistently uses her academic title in order to inspire women and members of other marginalized groups to pursue their dreams no matter what challenges those dreams may entail, and certainly one of her goals is to see more women in academia.

Dr. Martindill earned her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Missouri and taught there in the Sociology Department, the Peace Studies Program and the Women’s and Gender Studies Department. Her areas of emphasis include political sociology, organizations and work, and social inequalities. Dr. Martindill’s dissertation focuses on the no-kill shelter social movement and is based on ethnographic research conducted during several years of working in an animal shelter. She is vegan, a feminist and is currently interested in the stories women tell through their needlework, including crochet, counted cross stitch and quilting. It is important to note that Dr. Martindill consistently uses her academic title in order to inspire women and members of other marginalized groups to pursue their dreams no matter what challenges those dreams may entail, and certainly one of her goals is to see more women in academia.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and is a member of the Research Advisory Council of The Vegan Society. She has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute and has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Environmental Values, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and is a member of the Research Advisory Council of The Vegan Society. She has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute and has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Environmental Values, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).