By: Dr. C. Michele Martindill

A recent blog post essay by Unfriendly Black Hottie (Hottie, 2013) should have prompted an open discussion of the appropriation of intersectionality in the so-called vegan abolitionist animal rights community. So far, that discussion has yet to happen. Why not? Is it another case of a white-centered social movement making Blacks invisible and silencing their voices? Are movement members who use the concept of intersectionality unwilling to or afraid to critically examine their understanding of the concept? To what extent does white fragility (Diangelo, 2011) (see definition of white fragility below) come into play as an explanation for the lack of discursive dialogue? Under the best of circumstances it is painful to examine values and beliefs we hold close to our hearts and to do so with the knowledge we may be wrong. Critical analysis can lead to that feeling of sickness in the pit of the stomach or an unwelcome feeling of embarrassment. It can lead to disorientation and loss of control, rare feelings for those who have long benefited from white privilege and who have the power to define concepts such as intersectionality, appropriation, racism, sexism and feminism to suit their purposes. It can alternatively lead to learning, to growth and the impetus to make social change happen.

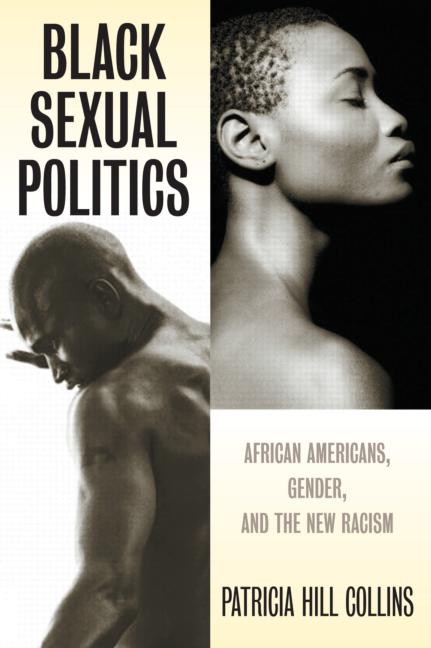

Intersectionality is one of the current buzz words in the vegan abolitionist animal rights movement. Some people love it, others hate it. The meanings are varied, confusing and debated across countless online discussion threads. One vegan blogger tells us that, “…intersectionality does not mean that all forms of oppression intersect” and they go on to define it as, “in specific situations, multiple forms of discrimination can create specific situations for a group not described by the forms of oppression that intersect. The primary example is the failure of racism and feminism to describe their intersection for women of colour” (Unknown, Intersectionality and Abolitionist Veganism: Part 1, 2014). The reader is left to wonder if the blogger is suggesting that racism alone or feminism alone cannot explain the “discrimination” experienced by women of color so then it is important to look at the interactive effect of these oppressions. While the blogger provides a brief history of how intersectionality “started to be used frequently in the 1990s and has become something of a fashion in academic circles, rather like “queer theory” in the 1980s,” no direct connection is made to Patricia Hill Collins and Kimberle Crenshaw, the originators of the concept, and queer theory is shoved to the background as nothing more than a trend.

Random comments sprinkled throughout the rest of the essay serve mainly to keep any discussion of intersectionality white-centered and to argue that veganism will bring everyone together to end all oppressions:

If people are really interested in intersectionality and ending human-on-human oppression, it seems to me that sexism in developed countries might be less urgent (and I say this as a woman) than wholesale slaughter of people, men, women, and children, in Gaza, Afghanistan, Yeman [sic], Syria, and Iraq and the culture of hatred that supports this destruction.

So, intersectionality in this instance becomes a method for rank ordering the form of oppression that most needs to be addressed, but in the next breath all of these oppressions are dismissed in favor of getting people to understand how only a commitment to being vegan will stop the large number of deaths:

Ending war, sexism, racism, oligopoly is important but change will only happen when society as a whole is affected. Veganism is something we can do now, and convince others to do now. It will only result in large social change when there are enough of us, but every single vegan has an impact on how many deaths occur, and it is something we can all do, right now.

Our blogger leaves us with a rationalization of how and why veganism is white-centered and why it such white-centeredness is not a problem:

Veganism is not the province of any race. Just because a majority of online vegans are “white”, that does not make it a “white” issue. I’d guess the majority of people commenting on police killings in the US are also “white”, even though the victims are generally “black”. I’d guess that’s an artefact of internet participation and availability of time, …and it’s changing.

Apparently, if Blacks are not visible online it is simply an “artefact of internet participation and availability.” White centeredness is not a numbers game. It specifically refers to how whites dismiss, ignore and otherwise make invisible the presence of Blacks. Did this blog author even look online for Black vegans? Our author continues:

I look at this issue, the current scurrying to shame abolitionist vegan advocates as racist, with dismay. The promotion of the idea that there are “exceptional” circumstances for people of colour, and that it is racist not to address these circumstances, is not helpful, …and I think it holds a certain contempt for people of colour. The issues of veganism are not different for people of colour. Our thinking is not different. We either recognise the autonomy, the moral personhood, of other animals, and respect them enough not to use them as things, or we don’t. There are no “special” economies for people of colour. Plant-based diets are cheap diets, and traditionally the diets of the poor. There are no “special” cultural conditions for people of colour in most parts of this global consumer world. [emphasis added]

Never mind that Black men are being murdered by the police, that racial profiling is rampant or that poverty rates are at an all-time high among POC, the message here is we can and should ignore intersectionality and just go vegan. Indeed.

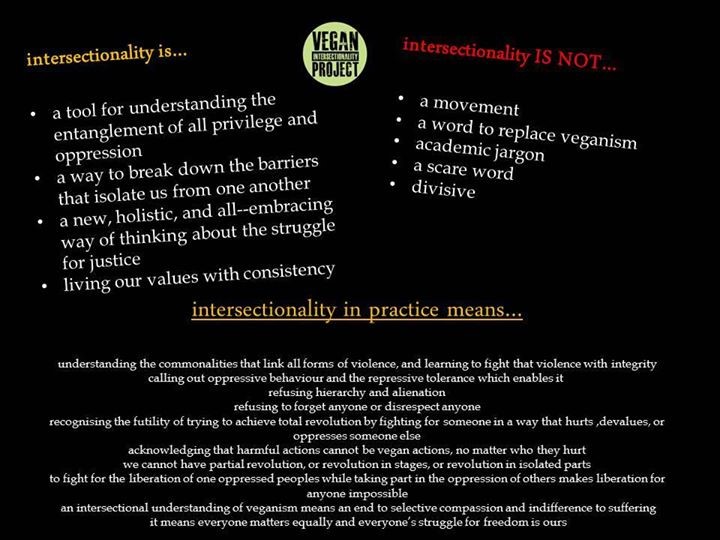

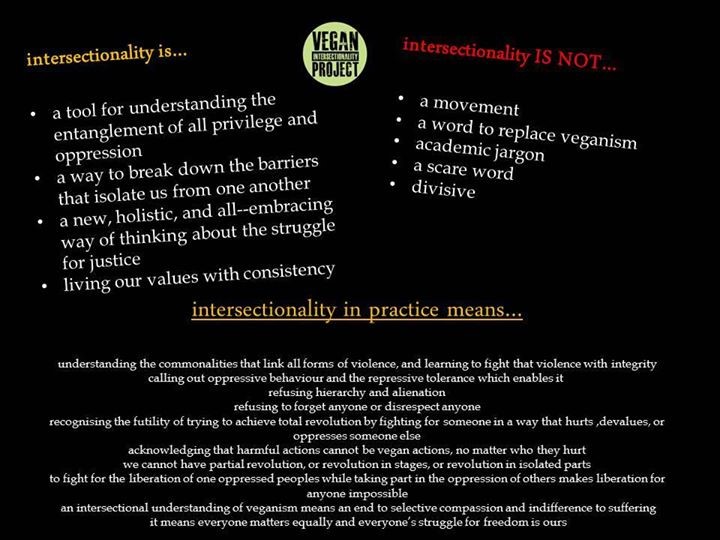

Another vegan animal rights Facebook page that was created specifically to promote intersectionality is The Vegan Intersectionality Project (Unknown, Vegan Intersectionality Project’s Photos, 2015). A single meme effectively sums up their definition of intersectionality:

Anyone researching intersectionality on this Facebook page will learn via bullet points it is “a tool for understanding the entanglement of all privilege and oppression, a way to break down the barriers that isolate us from one another, a new, holistic, and all-embracing way of thinking about the struggle for justice, [and] living our values with consistency.” Nowhere on the meme is there mention of or credit given to Patricia Hill Collins or Kimberle Crenshaw, nor is there so much as a tip of the hat to the notion that the concept of intersectionality was never meant to be white-centered. The meme concludes with a statement that is perilously close to the white-centered claim that all lives matter:

Intersectionality in practice means…an intersectional understanding of veganism means an end to selective compassion and indifference to suffering, it means everyone matters equally and everyone’s struggle for freedom is ours [emphasis added]

The author ignores the #BlackLivesMatter campaign which aims to center the discussion of racism with persons of color, and then the author proceeds to suggest that the Black struggle for freedom is the property of whites, that the struggles of others are shared or even owned by whites. How is that even possible? Are whites now being pulled over by police for the crime of driving while white? Are white men now being incarcerated in the prison industrial complex at rates that exceed those of Black men? Whites can never know or share the struggles of Blacks. Also, whites seem incapable of acknowledging the Black discourse on intersectionality, much to the detriment of veganism.

We are at a point now where we have to ask what white vegans are missing when they close their ears and minds to the Black understanding of intersectionality, when the result is the erasure of the lived experiences of Black women. In the essay on intersectionality from the Unfriendly Black Hottie blog the author describes a meeting with Patricia Hill Collins, a Distinguished University Professor of Sociology at the University of Maryland and the first to theorize intersectionality (Collins, 2005). Collins was asked, “How do you feel about the ways white feminists have taken your work on intersectionality as a feminist way to be more inclusive while erasing the creations as part of a Black feminist tradition and without a dedication to Black women’s lives in any way?” While Collins did not use the word appropriation to describe what happened with her work, she related a story of how white musicians took the works of Black jazz and blues artists and imitated them without having the lived experiences that inform the music. Technically, the music is similar, but in the process whites erased Black lives from the music, the very heart and driving force of the music.

The Unfriendly Black Hottie author goes on to summarize how Patricia Hill Collins views intersectionality:

intersectionality is meant as a bottom up approach, not a top down approach. those with power cannot be “intersectional”. you are also not living intersectional experiences. intersectionality was always about exposing the ways Black women are caught up in multiple systems of oppression, namely race, gender and class, but often many more. it is meant to help Black women understand their experiences in a white supremacist patriarchal culture like the U.S. or much of Western nations that have applied this model onto most cultures from the outside. most importantly, it is meant to help Black women see the ways their experiences are connected to one another and not a product of self-deficiency but structural real systems that have cultural and economic benefits for ruling/dominant classes. [emphasis added]

understanding Black women live intersectional experiences gives us insight into the ways race, gender and class, heterosexism and more all work together in ways that restrict Black womens access to resources. and access to resources is what is really one of the most important things needed in Black women’s lives. which white feminism is not committed to in any way. when Black women learn more about classism, sexism, racism, heterosexism and more (such as transmisogyny, islamophobia, convicted felon status, etc) and how they work, we learn more about how we can define ourselves without those systems imposing our identities onto us.

In other words, the white-centered, man-dominated leadership of the vegan movement cannot and should not be dictating the meaning and use of the concept of intersectionality. Vegan leadership has no direct experience of intersectionality. White men are a part of the very “white supremacist patriarchal culture” intersectionality is meant to challenge and thereby allow Black women to define themselves sans the systems of classism, racism, sexism and other oppressive systems. Whites are simply wrong to take intersectionality as their own:

when you’re white saying your an intersectional feminist, you are wrong. you are the white boy singing sad songs to a blues twang claiming to be a Blues artist. you are the miley who wears black womens bodies and perceived sexualities as fun identities to put on and off, without living within those experiences always and forever. it is erasure, it is warping, it is the continual narrative of whiteness as a dominant force, in opposing the creators and destroying the creators while then attempting to re-create those creations with whiteness firmly installed inside of it. which is false, warped, fake and without heart and soul. it is a lifeless imitation. and mostly, it isn’t REAL.

So, what is “REAL” as vegans come to terms with the white fragility born of realizing they appropriated a concept and misrepresented it? So far, silence or defensive posturing are the ‘go-to’ responses of vegan leadership, essayists and Facebook responders. They spout clichés such as “all lives matter” or “just go vegan” or “veganism is not about race” or “intersectionality shows the interconnectedness of all oppressions.” When anyone in the animal rights movement claims they are practicing intersectional veganism, defining it merely as wanting justice for all and being against all exploitation and oppression, they are operating under a misguided act of cultural appropriation. They are also working to insure that an upper class white cis gendered ableist man dominated ideology remains at the center of the vegan abolitionist animal rights movement. Intersectionality or pro-intersectionality is not a let’s-have-a-group-hug approach to social justice, nor is it simply a path to growing a revolution—increasing movement membership–that will end all oppressive social systems. If vegans want to be pro-intersectional, the term for those who support Black feminist intersectionality, then they have to acknowledge the history of the concept, stop trying to dismiss intersectionality as a distraction from veganism, and put an end to any practice that de-centers Blacks and inserts white dominance. Specifically, stop the following kind of commentary:

Abolitionist vegans are not being speciesist when they don’t let those raising issues of human oppression hijack a vegan forum. Abolitionist vegan advocacy forums are “non-human animal space” (Unknown, Intersectionality and Abolitionist Veganism; Part II, 2014).

The net effect of this message is to exclude Blacks from yet another white centered organization in much the same way they have been excluded for centuries and by making the all too familiar comparison of Black lives to those of animals, only this time Blacks are not as welcome as the animals.

It is no wonder that veganism is now seen as an apolitical mish-mash of diet fads. When people are told to just go vegan or that veganism is only for the animals, then what they are really being told is vegans are not serious about pro-intersectionality, about becoming an inclusive movement. The whiteness of the abolitionist vegan movement isn’t an illusion based on white online involvement—the whiteness of the movement happens because vegans are known for their appropriation of Black culture and history, e.g. abolitionism was taken without permission:

Abolitionism as it was first conceived was built and mobilized to free oppressed humans who continue to be oppressed. For vegan advocates to completely appropriate the language and ideas of this movement and then forsake suffering humans, abandon them in their time of need, aggravate their hurting, benefit from their hurting, and then accuse victims and survivors of selfishness is deplorable. Without a doubt, this approach will only further alienate anti-speciesist efforts, tarnishing it as yet another a space of violence, oppression, and white male Western privilege (Wrenn, 2014).

Dismissing and ignoring the suffering of humans makes a mockery of anti-speciesism, of its aim to stop rank ordering others based on their perceived value. Vegans need to stop putting whites at the top of the ladder, granting them the power to tell others who matters and who doesn’t, who should be heard and who shouldn’t. White fragility, that roller-coaster-whooshy feeling in the pit of the stomach, can be a signal to stop rationalizing the status quo and to stop colonizing Black spaces in order to appropriate their language or whatever else abolitionist vegans deem useful. Stop appropriative behaviors. At the same time, know it is not putting humans over the animals when we practice pro-intersectionality; rather, it is centering and respecting the resistance of Black feminists, resistance to the racism, sexism, ageism, classism, ableism and speciesism of a white man dominated patriarchal society. Veganism was never meant to be a justification for white dominance or appropriation.

Definition of White Fragility:

White Fragility is a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves. These moves include the outward display of emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and behaviors such as argumentation, silence, and leaving the stress-inducing situation. These behaviors, in turn, function to reinstate white racial equilibrium. (Diangelo, 2011)

Dr. Martindill earned her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Missouri and taught there in the Sociology Department, the Peace Studies Program and the Women’s and Gender Studies Department. Her areas of emphasis include political sociology, organizations and work, and social inequalities. Dr. Martindill’s dissertation focuses on the no-kill shelter social movement and is based on ethnographical research conducted during several years of working in an animal shelter. She is vegan, a feminist and is currently interested in the stories women tell through their needlework, including crochet, counted cross stitch and quilting. It is important to note that Dr. Martindill consistently uses her academic title in order to inspire women and members of other marginalized groups to pursue their dreams no matter what challenges those dreams may entail, and certainly one of her goals is to see more women in academia.

Dr. Martindill earned her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Missouri and taught there in the Sociology Department, the Peace Studies Program and the Women’s and Gender Studies Department. Her areas of emphasis include political sociology, organizations and work, and social inequalities. Dr. Martindill’s dissertation focuses on the no-kill shelter social movement and is based on ethnographical research conducted during several years of working in an animal shelter. She is vegan, a feminist and is currently interested in the stories women tell through their needlework, including crochet, counted cross stitch and quilting. It is important to note that Dr. Martindill consistently uses her academic title in order to inspire women and members of other marginalized groups to pursue their dreams no matter what challenges those dreams may entail, and certainly one of her goals is to see more women in academia.

References

Collins, P. H. (2005). Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism. Routledge.

Diangelo, R. (2011). White Fragility. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 54-70.

Hottie, U. B. (2013, November 6). Unfriendly Black Hottie. Retrieved from Unfriendly Black Hottie: http://femmefluff.tumblr.com/post/66233480328/like-being-very-clear-when-i-asked-patricia-hill

Unknown. (2014, December 14). Intersectionality and Abolitionist Veganism: Part 1. Retrieved from Abolitionist Veganism: Issues in the Movement: https://veganethos.wordpress.com/2014/12/14/intersectionality-and-abolitionist-veganism-part-i/

Unknown. (2014, December 26). Intersectionality and Abolitionist Veganism; Part II. Retrieved from Abolitionist Veganism: Issues in the Movment: https://veganethos.wordpress.com/2014/12/26/intersectionality2/

Unknown. (2015, April 17). Vegan Intersectionality Project’s Photos. Retrieved from Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/774093712704517/photos/pb.774093712704517.-2207520000.1430768357./774431842670704/?type=1

Wrenn, C. (2014, December 13). Intersectionality is a Foundational Principle in Abolitionism. Retrieved from The Academic Abolitionist Vegan: http://academicabolitionistvegan.blogspot.com/search/label/Intersections