By Dr. C. Michele Martindill

“WHAT WOULD DONALD WATSON DO?” How Does that One Question Promote Sexism and Prevent Inclusiveness in the Vegan Abolitionist Movement?

What sacrilege! How dare any vegan suggest anything negative about the man who coined the term veganism! ::gasp:: Read the title again. Donald Watson is not the problem, nor is his work to end the suffering of animals the issue. The problem is how vegans today invoke Watson’s name and his definition of veganism as a cure-all whenever there is a dispute in the movement, and in so doing fail to use critical and reflexive thinking to understand why the vegan abolitionist movement is floundering.

If someone asks why the vegan movement is almost entirely comprised of women, but the leadership roles are filled by men spewing ideologies born of patriarchy, they are told veganism is only about helping the animals. A question about how a vegan group could have a logo steeped in ageism is met with the observation that we have to keep the focus on the animals and not worry about ageism; besides, the caricature logo of an old man and woman are meant as a joke. When someone asks why Persons of Color are largely absent from the vegan movement, the response is that that they could be vegan if they wanted to, but they choose not to be vegan.

In each instance there is usually a reminder that veganism is only concerned with the animals, and the name of Donald Watson and his definition of veganism are raised to punctuate the end of the conversation. The vegans who see veganism according to this very narrow understanding of veganism might as well be asking What Would Donald Watson Do? (WWDWD?)—a play on the ubiquitous What Would Jesus Do? refrain. In each instance where the movement excludes women, older people, POC, the lower classes or people with disabilities WWDWD? Meanwhile, those from marginalized groups are left to wonder how a white man from an age of white supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism and imperialism could be the final word on ending oppression and exploitation.

Vegans are for the most part well aware that Donald Watson came up with the term vegan in 1944 as a way of both differentiating his previous commitment to being a vegetarian from his new vision of how humans should relate to their environment, and as a name for his newly founded society of like-minded individuals, the Vegan Society. Many can recite his definition of veganism from memory:

[…] a philosophy and way of living which seeks to exclude—as far as is possible and practicable—all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals for food, clothing or any other purpose; and by extension, promotes the development and use of animal-free alternatives for the benefit of humans, animals and the environment. In dietary terms it denotes the practice of dispensing with all products derived wholly or partly from animals.

It was a radical statement for 1944 as well as for vegans today, and Donald Watson was surely a radical in his time. Right?

One current leader in the abolitionist vegan movement contends that Watson’s definition of veganism is meant to inspire vegans to work toward social justice for humans as well as other animals, but he also states that radical veganism died decades ago, replaced by consumerism. This leader questions how vegans can be more concerned with a new brand of chocolate bar suitable for vegans than with the corporatization of the Vegan Society and similar groups, groups that garner large donations to pay high salaried executives. How is it that veganism succumbed to capitalism? Here’s a better question: How radical could Donald Watson or his concept of veganism be when they emerged from a society steeped in white supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism and imperialism? Keep in mind that this question is not meant to label Watson, but to help us understand how systemic oppressions affect social action and how the foundation of the social movement leaves it vulnerable. There is no personal attack on Watson in this essay.

Radical is a socially constructed concept, which is to say the definition of radical changes according to the historical and local contexts in which the word appears. Within Donald Watson’s social world of 1944 England it was no doubt radical for him to not eat meat and to further stop using all other forms of animal by-products. Still, much to the frustration of some vegans in 2015 there is no strong statement from Donald Watson that could be applied to other social justice concerns of his era or ours. We can ask WWDWD? with regard to sexism, racism, ableism, classism or ageism, but there are no definitive answers to guide the vegans who campaign for inclusion of marginalized groups in the abolitionist vegan movement today, an effort that recognizes the intersectionality of how people identify with particular groups according to gender, race, physical abilities, social class and age.

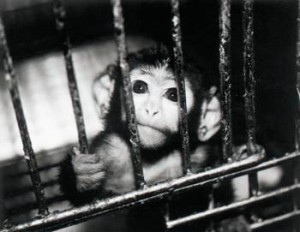

We can never know what Watson intended. Knowledge of anyone’s intentions requires the ability to read minds. We only have actions and historical context to analyze. We know that Watson was enabled to form the Vegan Society through his position in a society that respected the work and ideas of white men like Watson; however, he was also constrained in the extent to which he could promote social justice for all marginalized human groups when asking others to consider veganism because calling for an end to the use of animals for human purposes was such a radical request. It required many explanations, and it is not difficult to imagine the near overwhelming backlash he faced from the corporations and politicians that benefitted from the exploitation of animals. Watson was a radical challenging the mainstream belief that other animals were merely objects for humans to use as they pleased—for food, for scientific experiments, for farm work, for clothing, for transportation, and for entertainment. So, we are left with many questions about how the abolitionist vegan movement of today remains predominantly white, still grounded in patriarchy and making a dismal effort at inclusivity.

A recent online discussion highlights the difficulty in relying on Watson to be the final arbiter of how the movement can become inclusive. When members of a group were questioned about the sexism in the movement, one man responded that structural or systemic sexism has always been around so there was no reason to worry about it. His concern was that someone in the discussion suggested Donald Watson was not a radical, but a product of a white supremacist society. He wanted to defend a perceived insult toward another white man rather than take seriously the sexism in the movement. Another man jumped in to claim the movement has always had plenty of women prominent in its leadership, and he proceeded to play the counting vaginas1 game by naming all of the famous vegan women. He even pointed out that Watson’s wife was in on the process of creating the word vegan, no doubt at the kitchen table. Others suggested that outside of the United States women lead animal liberation groups and are not all “thinking like men,” thus suggesting that sexism is relative to certain geographic locations and not to be found in the United Kingdom, New Zealand or Australia, for instance. All of these responses miss the main point: it doesn’t matter how many women organize or lead activities in the abolitionist vegan movement as long as we are living in a society dominated by the ideologies, social structures and movement strategies of white men.

At a time when the vegan abolitionist movement most needs to address its lack of inclusiveness, it is mired in defensive posturing and denial. As long as men are quick to claim #notallmen (McKinney, 2014) in their responses to concerns about sexism, we are left to think there are just a few bad individuals and efforts to end systemic sexism are in turn stifled. Corporatism and capitalism thrive in so-called vegan societies and organizations because we don’t acknowledge how the abolitionist vegan movement grew out of the man dominated white supremacy of our social world. Not one of us can escape the influence of these social structures unless we question and challenge their existence. Women are not completely constrained by patriarchal social structures, but they do have to become conscious of how those structures work, how they affect all women and then actively dismantle them to make space for structures that combine equity, compassion and peace.

What about men?

Telling women in the abolitionist vegan movement to quit making trouble by complaining about sexism is a way of defending the power and leadership of the men in the movement. Telling women that there were and are plenty of women in leadership roles or that the movement is primarily made up of women is a smokescreen that diverts attention from how men maintain their status and privilege. Telling women to focus only on the animals and to stop making the movement look bad is another way men perpetuate their positions of power. Men might as well be saying they do not want to discuss gender inequalities and prefer to tell women how best to serve the interests of men. Men consistently interrupt women in both online and face-to-face conversations about veganism, aiming a barrage of questions at them, questions that constitute microaggressions against women (Khan, 2015).

maintain their status and privilege. Telling women to focus only on the animals and to stop making the movement look bad is another way men perpetuate their positions of power. Men might as well be saying they do not want to discuss gender inequalities and prefer to tell women how best to serve the interests of men. Men consistently interrupt women in both online and face-to-face conversations about veganism, aiming a barrage of questions at them, questions that constitute microaggressions against women (Khan, 2015).

Here’s a sampling of such questions:

- How can you say there is sexism in the movement when Donald Watson’s wife helped with his work? [note: it’s always HIS work, not HER work that is cited]

- How can you say there is sexism when women of the 1980s organized and carried out liberation activities, and we see women continuing to do the same?

- How can you say there is sexism when we need to be concerned with spreading veganism, especially since veganism will lead to the end of sexism?

- How can you say there is sexism when you’re the only one who’s being sexist? You don’t even know the meaning of being sexist. I know sexism and you’re not even close. It’s sexist for you to call me sexist.

AND ONE MORE THING:

Men need to put themselves in the positions of marginalized group members and think about how it sounds when a white man quotes another white man–Donald Watson in this case–when defining veganism. We need to hear the voices of women in the movement. Don’t just quote women to women. Step aside and know women can speak for themselves! Radical.

Works Cited

Khan, A. (2015, January 18). 6 Ways to Respond to Sexist Microaggressions in Everyday Conversations. Retrieved from Everyday Feminism: http://everydayfeminism.com/2015/01/responses-to-sexist-microaggressions/

McKinney, K. (2014, May 15). Here’s why women have turned the “not all men” objection into a meme. Retrieved from Vox: http://www.vox.com/2014/5/15/5720332/heres-why-women-have-turned-the-not-all-men-objection-into-a-meme

Notes

1. Meant as a figure of speech; not all women possess vaginas. White men in the movement don’t even realize there are trans or other gender identities. They still see the world in binary form. If they do see multiple genders, it’s still only vaginas they want or count in the movement.

Dr. Martindill earned her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Missouri and taught there in the Sociology Department, the Peace Studies Program and the Women’s and Gender Studies Department. Her areas of emphasis include political sociology, organizations and work, and social inequalities. Dr. Martindill’s dissertation focuses on the no-kill shelter social movement and is based on ethnographical research conducted during several years of working in an animal shelter. She is vegan, a feminist and is currently interested in the stories women tell through their needlework, including crochet, counted cross stitch and quilting. It is important to note that Dr. Martindill consistently uses her academic title in order to inspire women and members of other marginalized groups to pursue their dreams no matter what challenges those dreams may entail, and certainly one of her goals is to see more women in academia.

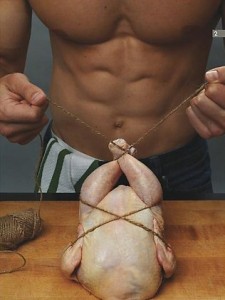

Animals are imprisoned and assaulted in our homes, corrals, barns, laboratories, rodeos, horse races, circuses, zoos, aquariums and fight rings. Women are detained and abused in prostitution, brothels, rape camps, strip clubs, peep shows and in their homes. It is men who typically control these forms of enslavement of women and animals. Domesticated animals are cooked and photographed in sexual postures as the pornography of meat. Women are sexually depersonalized in and by pornography. Harassment is common to either group. Animals and women are most frequently killed by men, and some women have been slaughtered, eviscerated and dismembered like animals by men. In addition, societal assumptions in general that animals “exist” for human welfare should not sound totally different from women’s experiences under male expectations. Even the therapeutic role animals and women play correlate. Most people live their entire lives without learning of the barbarity that occurs behind the closed doors of brothels, pornography studios, massage parlours, sex trafficking, strip clubs and private dwellings on the one hand, and slaughterhouses, vivisection labs, animal entertainment industries, animal traffickers, product-testing facilities, factory farms and households on the other. The business of exploiting women and animals for pleasure, convenience, amusement, taste and moneymaking is intentionally well hidden. Disclosure would undermine the power and profit of male capitalist and socialist enterprises. Men must have their sex and steak at all costs.

Animals are imprisoned and assaulted in our homes, corrals, barns, laboratories, rodeos, horse races, circuses, zoos, aquariums and fight rings. Women are detained and abused in prostitution, brothels, rape camps, strip clubs, peep shows and in their homes. It is men who typically control these forms of enslavement of women and animals. Domesticated animals are cooked and photographed in sexual postures as the pornography of meat. Women are sexually depersonalized in and by pornography. Harassment is common to either group. Animals and women are most frequently killed by men, and some women have been slaughtered, eviscerated and dismembered like animals by men. In addition, societal assumptions in general that animals “exist” for human welfare should not sound totally different from women’s experiences under male expectations. Even the therapeutic role animals and women play correlate. Most people live their entire lives without learning of the barbarity that occurs behind the closed doors of brothels, pornography studios, massage parlours, sex trafficking, strip clubs and private dwellings on the one hand, and slaughterhouses, vivisection labs, animal entertainment industries, animal traffickers, product-testing facilities, factory farms and households on the other. The business of exploiting women and animals for pleasure, convenience, amusement, taste and moneymaking is intentionally well hidden. Disclosure would undermine the power and profit of male capitalist and socialist enterprises. Men must have their sex and steak at all costs.