Macra na Feirme, a farmer’s association in Ireland, is creating a pornographic calendar to raise awareness about mental health problems and suicide in the farming community, particularly that of young men.

This project is gendered, as pornography predominantly involves the display of women’s bodies, while farming is masculinized. Women are the objects on display, while men are the subjects of concern.

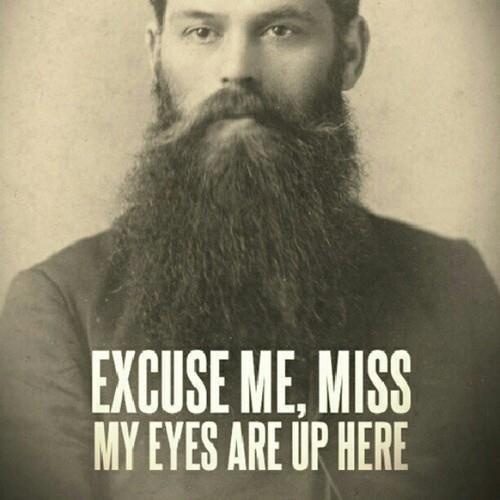

What is interesting is that the campaign seeks to challenge unrealistic masculine gender roles (which discourage boys and men with depression from seeking help or admitting weakness), and yet those same roles are protected by framing the campaign in clear scripts of patriarchal dominance.

Importantly, the centering of men’s experiences also makes invisible the multitude of research that shows clear correlations between the sexual objectification of women and women’s higher rates of depression, anxiety, and self-harm, as well as lower rates of self image and self efficacy.

But more is going on in these images–we’re also seeing the romanticization and sexualization of speciesism. In one image, the Rose of Kilkenny (Ireland’s version of Miss America), poses seductively with a milking device. An instrument of torture for the Nonhuman Animals involved, but a very naturalized symbol of power, domination, and the pleasurable consumption of the female body for humans who interpret the image.

What’s also made invisible is the relationship between mental health and participation in systemic violence against the vulnerable. Yes, the campaign seeks to bring attention to the emotional challenges associated with farming, but no connection is being made to the relationship between hurting others and the hurt one experiences themselves. Slaughterhouse workers, for instance, are seriously psychologically impacted by the killing and butchering they must engage. Dairy workers, too, are paying a psychological price for their participation. This isn’t just about “farming” in general, this is about speciesist practices in particular. Speciesism hurts us all: Nonhuman Animals in particular, male farmers as a consequence, and women who are objectified and hurt in a society where the exploitation of feminized vulnerable groups is normalized.

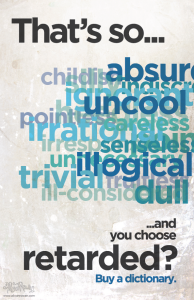

Indeed, I find it interesting that, for women who want to participate in a social movement, the “go to” response is so often to get naked or make pornography. It is a powerful statement about the gender hierarchy in our society and the limited and often disempowering choices available to women. Ultimately, it speaks to a considerable limitation on our social justice imagination.

Thank you to our Hungarian contributor Eszter Kalóczkai for bringing attention to this story.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.

![“Walter [the hunter who is also a dentist] says he killed Cecil [the lion] because he didn’t know his name… Let’s hope Walter knows his patients’ names.”](https://veganfeministnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/DXE-Cecil.jpg)