Content warning/Not Safe for Work: This article (and pages it links to) contains information about sexual assault and racial violence which may be upsetting. Some quotes contain strong language. Many images included are graphic and disturbing.

Photo credit Xandrah-Octopus

By shawndeez davari jadalizadeh

Last month, on September 26, people gathered in city centers to take part in the international day of protest, Respect Life. Spanning across seventy cities worldwide, the Respect Life protest “is to bring animal liberation to the forefront of human consciousness.” The goal, as stated by the organizing group 269 Life, is to raise awareness about the “animal holocaust.” Many praise the group 269 Life for its daring animal rights activism and participate in their international calls to action. However, there is a growing consciousness in the broader animal rights movement that this group is in fact rooted entirely in unsound ideology. Only three years old, the Israeli animal rights group 269 Life is undoubtedly the largest animal rights group in Israel. With significant followership across the globe, understanding 269 is the key to understanding the Israeli animal rights movement more broadly.

The foundation of 269 is based on a Declaration entitled the Non-Humans First Declaration which unequivocally defines human oppressions, such as racism, sexism, classism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, etc., as irrelevant and unimportant to fighting for animal rights. The Declaration consists of three main Articles, the first of which is that “no one should be excluded from participation in animal rights activities based on their views on human issues.” Making clear the disregard for human oppression, the Declaration specifically makes room for activists who have no interest in intersectionality. In particular, this defining Article condones racism, sexism, classism, ableism, homophobia, and transphobia in the animal rights movement by allowing activists to enter without engaging a critical stance on systematic oppression. This type of mandate allows individuals who do not want to struggle against the arduous and complex network of oppressions to join a movement where they can participate in animal rights activism, while continuing to be racist, sexist, homophobes.

The second article states that “tactics should prioritise non-human animals” and that “no tactical idea should be excluded from the discussion based on its conflict with human rights ideology.” This point is imperative in understanding 269’s style of activism. Famous for their brutal and inflammatory demonstrations, 269 has a history of engaging in protest tactics which involve violence against human beings.

For example, the group conducted a “performance” in which a group of men wearing all black ski masks abduct a young woman, rip her baby away from her, and forcibly milk her like a cow while beating her, all on a public sidewalk. In yet another instance of senseless and offensive activism last year, 269 activists donned pointed white hoods covered in blood, eerily resembling the KKK. Corey Wrenn describes the problematic nature of one of 269’s branding demonstrations in how “these branded men in chains draw on a history of human slavery. There’s something disturbing about white skinned activists from a mostly white organization reenacting a history of racial oppression while simultaneously failing to acknowledge it in their narrative.” Triggering and traumatic, 269’s approaches to animal rights are perpetuating very real notions of violence against women, People of Color, and children.

The third and final article of the Declaration is a “call on human beings to free their own (non-human) slaves before demanding their own rights.” Building off of an embedded privilege, the language of the Declaration implies that humans are to give up concern and pursuit of their own rights. Evidently, individuals with identities which face more systematic oppression (People of Color, women, working class, queer, disabled, etc.) will likely not be able to get behind the concept of putting the animals’ first, nor should they, as simply surviving is often a struggle. It is in this Article where all the privileges apparent in the rationale behind the 269 Declaration manifest. It is also more than apparent in the title as well as the language of the Declaration that this is fundamentally an agenda to promote animal rights at the expense of human rights, under the guise of “urgency” for animals.

The central issue with the Non-Humans First Declaration is that it openly calls for classification of animal oppression as wholly more important and necessary to fight than human oppression, in addition to inviting racists and sexists to join the ranks. As a fixture of Israeli animal rights, we must note that the Non-Humans First Declaration is publicly signed by the founder of the group, Sasha Bojoor, as well as four 269 Life chapters. Therefore any group which supports the Non-Humans First Declaration, 269 Life in particular, should be seen for what it is – an anti-intersectional animal rights group, which not only accepts, but normalizes violence against humans.

269’s staunch Non-Humans First stance, as well as their sizeable global followership, demonstrates a structural problem within the animal rights movement today. Emblematic of the underlying oppressions embedded in animal rights activism more generally, 269 openly houses and nurtures anti-intersectional activists. In particular, their activism which champions violence against women, children, and People of Color, fortifies violence against traditionally oppressed bodies. Therefore, activists and groups which continue to collaborate with 269 should be rebranded as anti-intersectional.

Examples of Problematic 269 Activism

Because 269 uses the fundamentally problematic Non-Humans First Declaration as their manifesto, the activism which emerges from 269 is likewise deeply troubling. Almost all of their strategy is designed to evoke visceral reactions, generated in large part by acts of violence against humans. In performing these actions however, hegemonic narratives of violence against certain bodies are reified and therefore normalize those perceptions.

The following sections are designed to help outline the varying problems with 269’s attempt at activism. Due to the complex networks of oppression, it is entirely impossible to remove race analysis from gender analysis, so on and so forth. Therefore, I have chosen to place examples under general titles to which I believe they best fit. However there is an undoubtable overlap between oppressions and I acknowledge that certain examples could be placed in multiple categories.

Violence Against Women

One of the most basic violences which 269’s activism contributes to is their recurring activist theme of violence against women. Their activism entirely disregards historic and ongoing power dynamics of male supremacy. In fact, a majority of their actions rely heavily on the subordination, suppression, or violent attack of women, almost always conducted by men.

Street demonstration, men holding down a woman who is screaming as she is branded with a hot iron

Street demonstration; two men lead a woman dressed in white wearing a cow mask, head down

Street demonstration, woman winces as she is branded with a hot iron by a man

The repetitive performance of violence against women’s bodies is unhelpful, to say the least, in challenging the very real threats which women today face all over the world. In case it is unclear to 269, domestic violence, sexual assault, and murder are still rampant worldwide social ills. It is now well-known that one in three women globally will be beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused in her lifetime. As 269 continues to conduct these demonstrations in city centers across the world, their “activism” actually works to normalize this violence against women.

By designing these deeply gendered performances, 269’s work supports the notion that violence against women is possible, and worse, acceptable.

|

Irrespective of the consensual nature of the act, meaning even if we are to assume that the woman has agreed to participate of her own accord in an action which deliberately brings harm to her body, the violence still occurs. And 269 uses that violence against her body as a performance by which to sell, or advertise, the idea of veganism. Through a deeper understanding of the gender violence perpetuated in 269’s activism, the parallels between their stunts and capitalist exploitation of female bodies becomes eerily similar. By designing these deeply gendered performances, 269’s work supports the notion that violence against women is possible, and worse, acceptable. The repetitive production of such gendered violence further supports that conclusion.

Considering that our society has conditioned us to accept violence against women’s bodies as a routine or nonsignificant norm, the recreation of this particular violence continues to enforce that understanding. The repetitive consumption of violence against women’s bodies works to make regular, or “normal,” the violence women experience. And any activism which contributes to these normalizations is incredibly dangerous.

In addition to their street demonstrations, some of 269’s poster designs are extremely troubling. One of the most egregious examples of this is a poster with the phrase, “Got Rape?” Wholly ignorant and disrespectful to human survivors of sexual violence, 269’s poster designs reify violence against women, with rhetoric indistinguishable from Men’s Rights Activists’. Their sheer disregard for the triggering aspects of their tactics and the violences they contribute to demonstrates either their overwhelming privilege, their ignorance, or a combination of both.

Gloved arm is forced into a milk carton that has bottom that resembles that of a cow. Reads, “Got rape?”

Maintaining Racial Hierarchies, White Supremacist Power Structures, and The Israeli Occupation

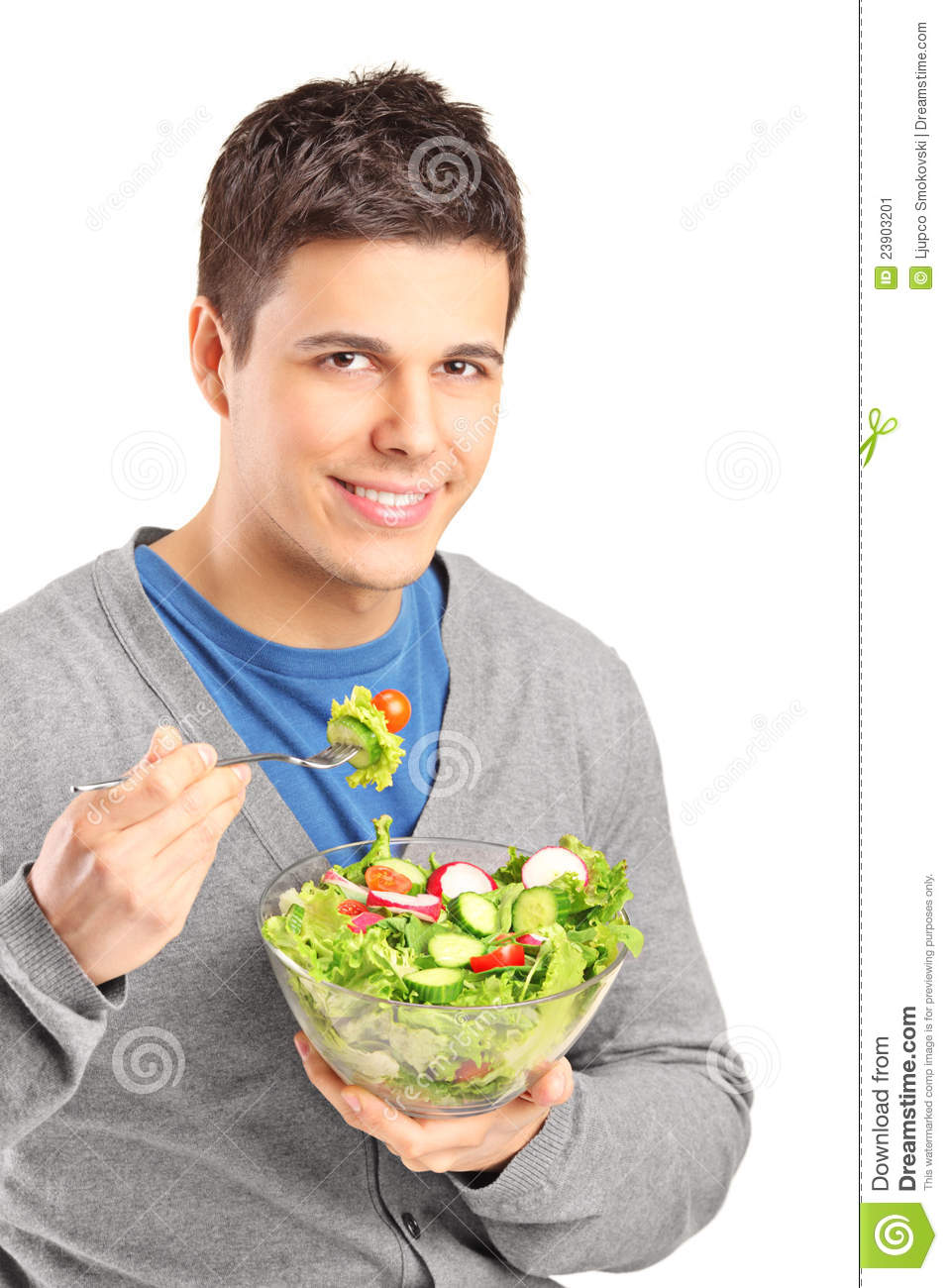

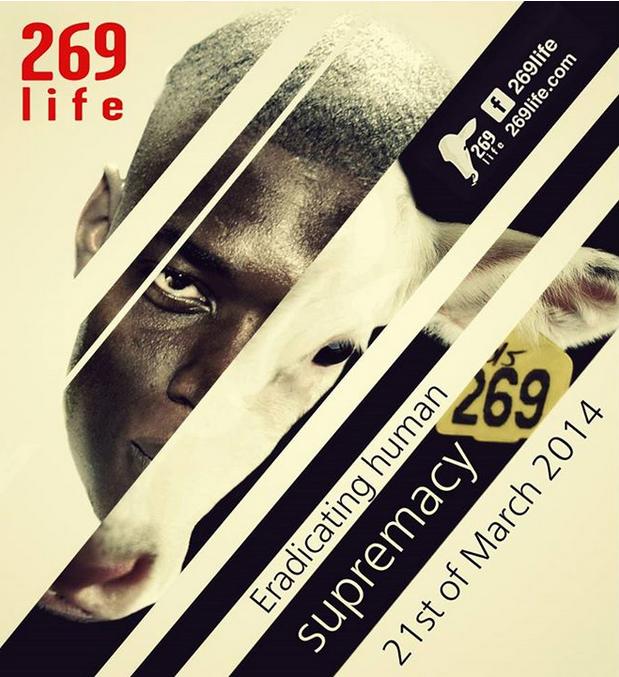

In addition to violence against women, 269’s activism contributes to maintaining racial hierarchies, white supremacist political power structures, and the Israeli occupation. Through much of their activism, 269 continues to circulate images which support existing racist structures. In one instance, the group used a highly offensive poster to advertise an event in March of 2014. The picture, shown below, situates an image of half of a Black male face adjacent to half of a white cow face with the words “Eradicating Human Supremacy.”

Poster for march, shows half of a Black man’s face juxtaposed with half of a white cow’s face

Firstly, given that this is one of the only, if not the only, times in which a Black individual is present in 269’s activism is a problem in an of itself, considering the severe anti-Blackness prevalent in animal rights activism. More importantly, the way in which they chose to depict this Black man’s face is wholly unsettling because it is not even designed to tokenize and represent this identity as a symbol of diversity for the group. Rather, the half-image is used to advertise for an event to “Eradicate Human Supremacy,” more clearly, to criminalize the Black individual as the symbol of wrongdoing in a speciesist society. The blatant insensitivity present in this photo demonstrates how 269 disregards the traumatic, horrific, and disgusting histories of worldwide slavery. Their choice of a Black man in this photo to visualize the eradication of human supremacy shows the complete lack of recognition of the ongoing human supremacy known as white supremacy.

An even deeper reading of the photograph allows for discerning the deeply embedded racist undertones by analyzing the juxtaposition of the Blackness of the Black face and the whiteness of the cow face. Given the said goal of the event and the ideology of 269’s Non-Humans First Declaration, animal life is seen as pure, sacred, and innocent as juxtaposed by the Black face, understood as the opposite of those qualities. Therefore, this construction of the Black face, seen as the human supremacist in the photograph, is defined in part by the contrast with the white cow face, seen as innocent and sacred. Additionally, the fact that the group leader, Sasha Bojoor, is responsible for circulating this image on social media as his Facebook profile picture further supports how the group leadership is oblivious to its perpetuation of anti-Black racism.

In addition to 269’s racist posters, one of their demonstrations for the Eradicating Human Supremacy Day in Italy exemplifies how ignorant and disrespectful they are with respect to race matters. Their description of the event reads as follows:

The 21st of March is the UN’s International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. We have chosen this day to continue spreading our message of animal liberation and call for the complete eradication of human supremacy over all other life forms! We are acting in unity with the UN’s intention for this day. The following excerpt is taken from their website: “The theme for this year’s event is ‘Racism and Conflict,’ highlighting the fact that racism and discrimination often are at the root of deadly conflict.” …We believe that there cannot be peace, nor an end to human prejudice while our hands are wet with the blood of billions of innocent animals!

Choosing to organize their day of action on the UN’s International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination is in effect seizing and dominating the one space and time set aside specifically for the discussion of racial violence. First, we have to recognize the painstaking difficulty of successfully centering race, racial violence, and the systematic oppressions of white supremacy at the United Nations. Knowing that it took strategic organizing and dedication on the parts of People of Color to centralize a discussion on race at the international level, it is simply absurd for animal rights activists, white animal rights activists, to interdict, claim, and take ownership over that space.

Instead of organizing their protest on another day, which would have allowed the much-needed space for the discussion of racial violence, they decide to take over and monopolize the space for their own ambitions, all while ignoring systemic racism within animal rights movements as an anti-intersectional group.

|

This is an upsetting manifestation of white animal rights activists downplaying the severity of racial violence and co-opting a space designed to address racial violence to meet their own needs. Furthermore, given that the 269 group could organize its demonstration quite literally any other day, demonstrates the arrogance of their activism. Instead of organizing their protest on another day, which would have allowed the much-needed space for the discussion of racial violence, they decide to take over and monopolize the space for their own ambitions, all while ignoring systemic racism within animal rights movements as an anti-intersectional group. The photo below is a part of their action, disrupting the space in front of the building which housed the meeting.

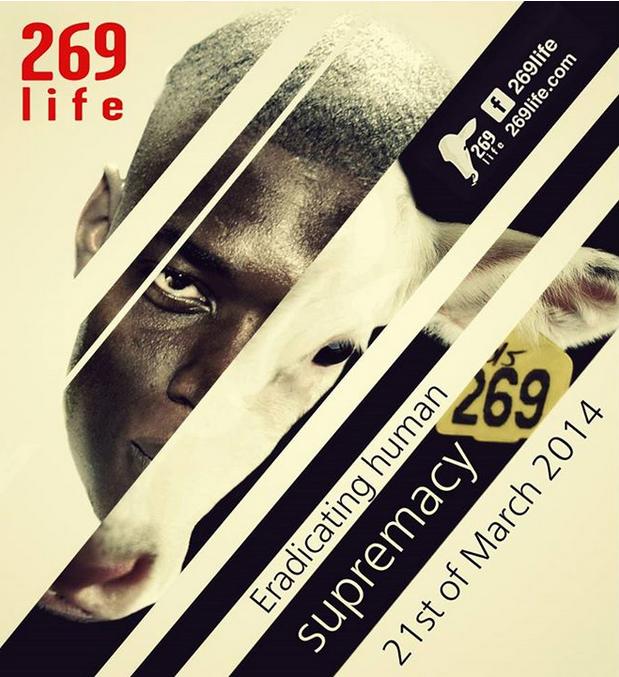

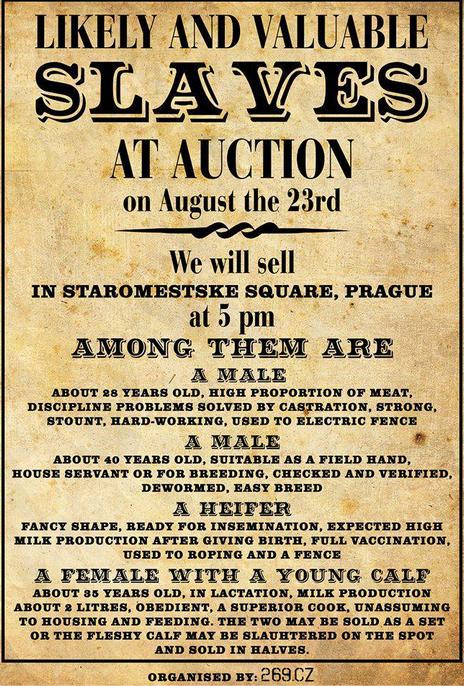

Continuing the trend of co-opting “International Days,” 269 Czech Republic also designed an action titled “Slave Auction Event.” In this blatantly derogatory event, a group of white Czechs simulated a human slave auction on the International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery.

Advertisement created by 269 Life that is brown with old font made to resemble a slave auction notice; refers to nonhuman animals

Live demo by 269life, shows white activists dressed as slaves on auction block

Drawing on the horrendous history of slavery, without due recognition, apology, or respect, this event is outright offensive. Again, co-opting a space which is not theirs to take and co-opting a history which is not theirs to reproduce, 269’s activism strategically swallows the space set aside to address the brutalities of slavery by staging a demonstration in front of the UN International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery Conference. In addition to being simply insulting, 269’s slavery-activism diminishes the material implications of slavery which still very much exist to this day. Shockingly self-serving, 269’s slavery-activism demonstrates how entirely clueless the group is to race, racial dynamics, and histories/realities of racial hierarchies.

Unfortunately, this is a recurring theme within 269 activism, in which white people repeatedly act as slaves, dawn chains, and get branded without taking any responsibility for their appropriative and insulting actions. As argued by contributors for Everyday Feminism, “comparing oppressions is violent and exploitative, particularly because black oppression isn’t over.” Exploiting Black history and recreating triggering visuals with an overwhelming degree of disregard for histories of slavery, 269 pursues its anti-intersectional activism while actively reproducing anti-Black racism within animal rights.

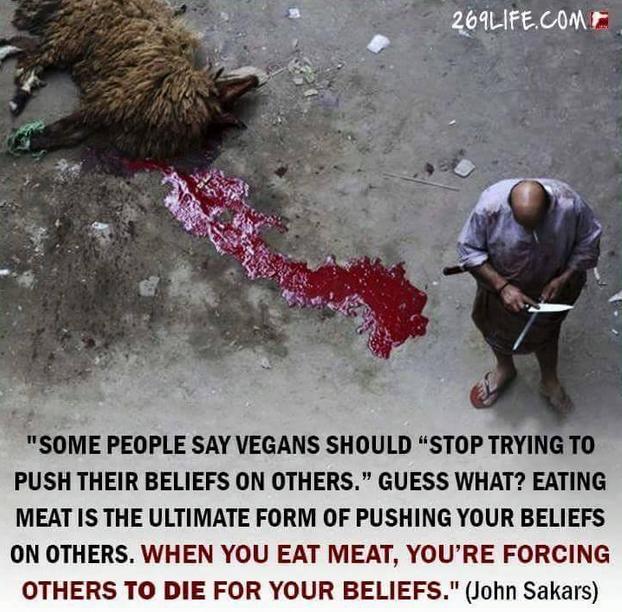

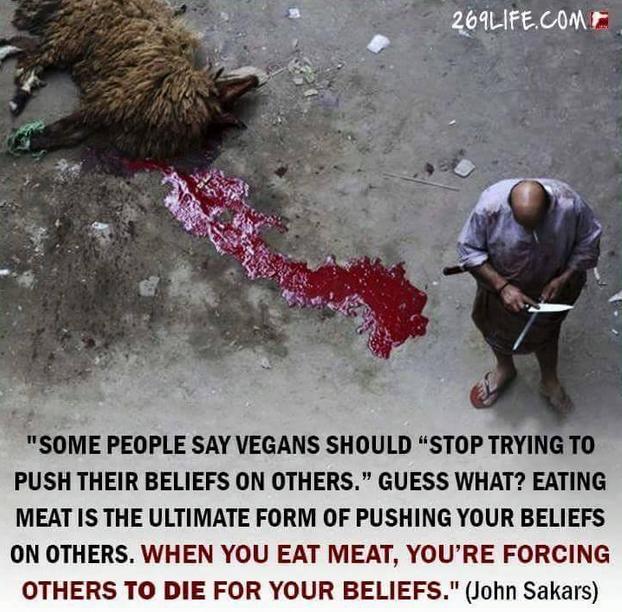

Another image circulated by 269 which fortifies racist hierarchies is an image of what is perceived to be a Person of Color over a slaughtered sheep.

Picture of a Muslim man who has just slaughtered a sheep. The sheep’s corpse lays in the street in a pool of blood as he cleans his knife.

The iconography in the photograph, along with the rhetoric “When you eat meat you’re forcing others to die for your beliefs” recreates the recurring problem of white-supremacist animal rights work. This type of whiteness-centric activism can be defined as activism organized and designed by white people and white groups in demonizing and targeting People of Color. In this instance, 269, an overwhelmingly white group is showcasing an image which falls quite literally into the whiteness-centric, racially profiling setup of “animal whites.”

Islamophobia is increasingly on the rise and entirely unaddressed within the animal rights community.

|

Furthermore, the Orientalism at play in this photograph contribute to existing Islamophobic notions of barbarity and savagery of Middle Eastern peoples. This point is not to be taken lightly, as Islamophobia is increasingly on the rise and entirely unaddressed within the animal rights community. Photos such as this which get widely circulated throughout social media reinforce Islamophobic and Orientalizing perceptions of Middle Easterners. In addition to the Orientalizing nature of some of 269’s activism, it is fundamental to outline how their unsound ideology manifests in violence towards human populations, in particular, the Palestinian people. An interview with Santiago Gomez, one of the original group members who participated in the original “branding” event in Rabin Square of Tel Aviv, shared his ideological transition of once being against the Israeli occupation to now supporting it.

The concept of “normalization,” borrowed from the Palestinian issue and applied to human/nonhuman interaction, was another peppery eye-opener towards the end of my time as a human rights activist. For those not familiar with the political parlance, “normalization” refers to any organization, group or program that brings together Palestinians and Israelis under vague and nonpolitical banners of “coexistence,” without direct and explicit acknowledgement of the occupation, apartheid, histories of displacement and the overall oppression of the former by the latter, as well as the need to combat it. It is essentially a way to whitewash oppressor/oppressed relations through the creation of a false sense of symmetry and sameness. And I maintain that the concept of a “one struggle” is a mechanism which basically serves the same purpose.

In this instance, Gomez is arguing a very nuanced yet crucial point to understanding his transition out of an intersectional activist stance. After outlining his epiphany of realizing the contradictions in his stance against the Israeli occupation, Gomez articulates his non-humans first stance by claiming that the concept of “one struggle,” or intersectionality, is equivalent to human supremacy. Therefore, Gomez is arguing that intersectionality is fundamentally a human-centric cause and that he himself disagrees with the efforts to challenge the occupation, apartheid, histories of displacement, and the overall oppression embedded in the Israeli occupation. Rooting his rationale in the Non-Humans First rhetoric, it is evident that his logic strategically dismisses, erases, and removes any concern with Palestinian rights. More broadly, his analysis is based on erasing context, or histories of violence, in order to focus all efforts entirely on animal rights work.

Gomez goes on in the interview to explain how he now supports the Israeli occupation because the embargo limits the number of cows allowed into Palestine and because Israeli military attacks have caused the near collapse of the Gaza fishing industry. He details his rationale beforehand as an intersectional activist who was insulted at such an argument and how he now supports the Israeli military occupation and violence towards the Palestinian people.

Further emphasizing his point, Gomez claims:

The oft-repeated argument that the animal rights movement should concern itself with human rights because “humans are animals too” would be a prime example of such a linkage, as would any reference to the low wages or dangerous work conditions of those poor slaughterhouse workers. The chant “human freedom, animal rights, one struggle, one fight!”—an ahistorical, apolitical, decontextualized and across-the-board flawed syllogism if there ever was one—would be a close third.

Citing the crux of intersectional activism, concern for human struggles, as an antithesis to his activism, Gomez illustrates his aversion to intersectional activism. Ridiculing the notion that humans are animals too as an arm of whitewashing oppressed/oppressor relations, Gomez is again, reifying the Non-Humans First Declaration.

Emphasizing his stances, Gomez unashamedly points to the ability of 269 Life to make its unequivocal stances against human rights issues.

For all the faults you may find with 269, it is at least free of that pernicious political inferiority complex which plagues animal rights activism, in that it is definitely *not* about seeking validation through pathetic attempts at riding the coattails of “more pressing” (read: human-centered) causes. And that’s pretty rare in our movement.

Boasting of 269’s disregard with “human-centered causes” as a “freedom,” Gomez’s articulation demonstrates the utter aversion to human rights. Not only is the group relieved to boldly align itself as a Non-Humans First group, it has in fact taken this disregard for human life and human well-being as a political advantage and worse, something to be proud of.

Nonetheless, Gomez does articulate at the beginning of the interview that these are his thoughts and his thoughts alone, not to be held as the ideals of the entirety of the 269 Life group. However, we must not ignore that this individual was one of the original members of the group and therefore has an ideological base which matched up with the founding members. More importantly, it is of crucial importance to note that the transcript of this interview has been publicly endorsed and shared by the founder and leader of the group 269 Life, Sasha Bojoor. In his public endorsement of the interview, Bojoor writes, “A true [Animal Rights Activist], completely dedicated to the cause and true to himself. Only wish, more activists had an infinitesimal portion of his integrity and intelligence.” Directly upholding Gomez’s positions, Bojoor’s public praise for Gomez shows how even the leader of 269 comes to support and endorse these oppressive stances.

The group has effectively designed a logic, the Non-Humans First pro-Israeli occupation logic, which permits its followers to support the Israeli occupation in justifying their animal rights activism.

|

Gomez’s logic, publicly endorsed and validated by Bojoor, demonstrate how the group is fundamentally a zionist group. By claiming the Non-Humans First stance, disassociating with human rights causes (Palestinian rights) entirely, and arguing that the occupation is actually good for animal rights as Gomez does, 269’s ideology becomes synonymous with zionist politics. The group has effectively designed a logic, the Non-Humans First pro-Israeli occupation logic, which permits its followers to support the Israeli occupation in justifying their animal rights activism.

Indeed, there are a few instances, either two or three, in which animal rights activists from Palestine have been invited to join in an animal rights demonstration with Israeli 269 activists. In one particular demonstration in the village of Shefa `Amr, activists gathered to distribute leaflets about veganism.

However, in the description of the demonstration, the 269 Life activists reinserted their sheer disregard for human life yet again by claiming, “Politics and nationalism means nothing, as long as the animals are suffering and dying by the billions, all over the world.” This argument may seem less offensive had it been coming from Luxembourg or Nepal, yet when it is coming from activists physically located in a country which is militarily occupying another country, attacking and slaughtering its people on a daily basis, and systematically annihilating their Palestinian identity, the language carries another meaning. It is effectively a method to reduce the Palestinian struggle to nothing and erase its significance.

For an Israeli based animal rights group to claim that “politics and nationalism means nothing,” while their government continues its violent military occupation and attack on Palestinian people is situating its activism in support of zionism. Just because Palestinians join 269 in a demonstration for animal rights does not mean that the group 269 is not supporting zionist politics. The political stances of 269 unequivocally demonstrate how the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land, the ongoing slaughter of Palestinian people, and erasure of Palestinian identity is of no significance to them whatsoever. It is imperative to understand how 269’s activism, regardless of whether or not Palestinians may sporadically participate, systematically deprioritizes the Palestinian struggle.

Normalizing Violence

Overall, 269’s framework and activism are deeply problematic in that they wholeheartedly support hegemonic narratives of violence and power. In addition to the racist, sexist, and zionist themes which flavor a majority of their tactical approaches to activism, 269’s leader Bojoor is also an adamant voice for violence against humans as well as being publicly against intersectionality. He is often seen sharing images, memes, and stories which support physical violence against humans.

Although all animal rights activists can, to some extent, understand the anger and frustration with humans which cause violence towards animals, the idea of encouraging violence towards humans cannot and will not resolve the issue of violence against animals.

|

For example, in reference to Kim Kardashian wearing fur, Bojoor writes that he “hope[s] that obnoxious piece of shit dies a slow and painful death. #fuckyouKimKardashian.” In another instance of supporting violence against humans, Bojoor shared an image which read “Save an animal. Encourage hunters to drink and drive.” Although all animal rights activists can, to some extent, understand the anger and frustration with humans which cause violence towards animals, the idea of encouraging violence towards humans cannot and will not resolve the issue of violence against animals. Suggesting the death of humans, no matter how much we disagree with them, is a clear articulation of irresponsible, ungrounded, and irrational activism. More importantly, it cannot bring about nonviolence or compassion towards animals, as Bojoor’s posts suggest.

Even more problematic, Bojoor deliberately and unequivocally stands against intersectionality as a baseline for social justice activism. He writes, “Intersectionality is a bankrupt ideology, the proof is easy to see, its all around us.” Whatever proof Bojoor is referring to, I have yet to see it. The only proof I am repeatedly encountering is how pathetically bankrupt anti-intersectional activism is ideologically. In addition to his emphatic anti-intersectional stance, Bojoor aligns himself with animal rights groups known to belittle and disregard intersectionality, such as PETA, Gary Yourofsky, and Direct Action Everywhere. It is no secret that Bojoor heavily cites, references, and endorses activism by each of these entities mentioned, and in so doing, solidifies his blatant disregard for intersectionality.

Conclusion

Given 269’s anti-intersectional stance, it is crucial to locate their narrow-minded activism within the larger scope of oppressive animal rights work. Proudly Non-Humans First, 269 Life continues to perpetuate violence against marginalized groups through its theoretical basis, social media materials, and social activism stunts. Acting as the apex of Israeli animal rights, 269 boasts its non-human animals first rhetoric in a cyclical reproduction of oppressive ideologies, targeting women, People of Color, Palestinians, and other oppressed groups. By strategically placing non-human oppressions as above, and therefore the only relevant priority, 269 structurally attracts animal rights activists which contribute to oppressive systems in an activism design which continues to make the world unsafe for marginalized groups.

In addition, it is critical that we mark 269’s activism as co-optive and exploitative of marginalized groups. By creating visually striking stunts to garner media attention, traction, and popularity in the animal rights community and beyond, 269 is profiting off of violence against oppressed bodies. Using this violence and its circulation as a means of increasing support, the group is in effect exploiting the oppressed for its own personal advancement.

This is a call to the global animal rights community: if you support 269 Life, you are supporting the oppression of human animals. To support 269 Life means to disregard the oppression of Palestinians, women, sexual violence victims and survivors, and People of Color. This group is a dangerous, violent, cooptation of compassion. If we seek to be intersectional in our approach to animal rights activism, there is no room for 269 Life in the movement, or animal rights groups which proudly associate with them. As intersectional animal rights activists, we must not fall for the trap of supporting a publicly anti-human rights group. Rather, we must do everything in our power to distance ourselves from a group known to align itself with such violence and disregard for human life. Although it may be initially tempting for those untrained to detect racism, sexism, and white supremacy, 269 is nothing more than a group of offensive, yet passionate, human oppressors. We must make clear in the animal rights community, yet again – the revolution will be intersectional or it won’t be my revolution.

shawndeez is a PhD student in Gender Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute. She has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).